Augustana researcher awarded “much money” to study “much marriage”

Tia Lalani - 8 December 2020

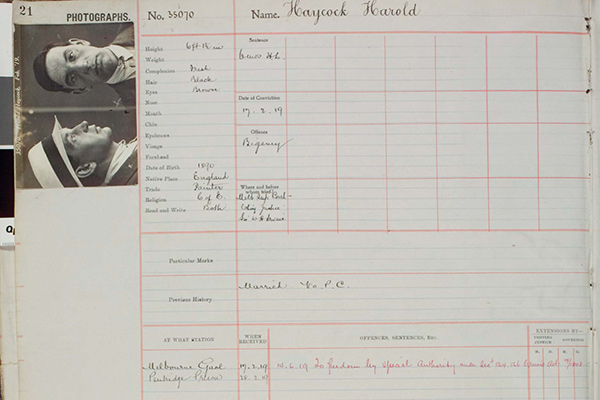

Professor Mélanie Méthot’s SSHRC funded research project will look at what offenses against marriage, like bigamy, say about the role of marriage throughout history. She, with the help of research assistants, will spend time combing through the thousands of case files and prison records, like the one picture above, for this exhaustive project. (Photo courtesy of Mélanie Méthot, from the Prosecution Project archives).

In 2001, Mélanie Méthot was researching intellectual history. She was combing newspapers to try to understand the thought process of social reformers and those who lauded them in the early 20th century. During her research, she came across three stories on bigamy in one newspaper and paused...that’s peculiar. Years later, she is armed with more stories of bigamy than she ever thought possible and a very large research grant to help her comb through them.

Professor Méthot’s project “Much Married: bigamy in Australia (1816-1950s)”, which was awarded a large Insight Grant through the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada’s competition, will look at the over 2500 bigamy cases that have been prosecuted in Australia since 1812.

“A nation of bigamists”

“Apparently, Australia is a nation of bigamists,” professor Méthot laughed, taking delight in the subject matter that has kept her interest for years. “But really, it’s because they’re a convict colony. It’s part of their history.” The Australian government has also put a lot of money into digitalization, which is why professor Méthot has such extensive resources available to her. Most of their newspapers have been digitized, and professor Méthot partnered with the Prosecution Project, which has been instrumental in digitizing all sorts of legal documents indexes, and in turn, has allowed her to locate court case files.

“It’s really rare that you get the chance to be this exhaustive,” professor Méthot explained while looking forward to diving into the over 100,000 hits for “bigamy” in Trove, the country’s digital library of historical newspapers. “The way I work as a historian is that I don’t have a hypothesis...I just let the data talk.”

And talk, this “data” certainly does. From stories of one minister who seemed to be involved with a number of bigamy cases while running a “marriage shop” of sorts, to individuals who committed bigamy but claimed intoxication during the first go-around, creating a null-in-void type of situation...though not in the eyes of the court, professor Méthot has seen it all. And although most of the cases that professor Méthot has come across thus far were simply informal divorces, they were--and still are--interesting and engaging, because, professor Méthot says, they are the stories of people. In fact, in Australia in the 1800s and early 1900s, people would go to watch divorces in court and bigamy trials as a form of entertainment. According to professor Méthot, “Newspapers delighted in providing tantalizing details on nearly every case of marriage breakdown.”

Towards modern marriages

Towards modern marriages

And although Professor Méthot’s project studies the past, it has much to do with the future.

“This research will allow us to see how the mentality has changed in relation to marriage throughout history because bigamy is an offense against marriage. I’ll also be able to find much about religion, gender roles, specifics for case files and individuals, etc. This research will have implications for contemporary debates about the nature, roles and meaning of marriage in Western societies.”

Professor Méthot was able to put these connections in the hands of her students during the undergraduate history course on marriage that she taught online in September. While giving them access to some of the case files, she also asked them to analyze a television show that dealt with marriage, and one student studied the Netflix series “Love is Blind”.

“Although we may associate marriage with love in the modern age, it wasn’t always for that purpose,” professor Méthot explained. “Marriage is still about inheritance, it’s still about how you regulate society, who is going to be in charge of the children, etc., but it’s certainly changed, in terms of both the law and practice.”

Student research at the forefront

Further than teaching the subject in her classes, professor Méthot has employed a handful of research assistants to help with her project and doesn’t plan on stopping there. She will continue to offer positions to students and will, in fact, be hiring again next summer. Half the time, the students work on a general grid of analysis, while they are free to pursue something that may have sparked their own interest the rest of the time, towards the end of being able to co-author papers and articles with professor Méthot.

“The benefit of the SSHRC, much more than what I’m going to find, is the ability to mentor students,” professor Méthot said. “When I think about my career, I think I have much more impact in the classroom than anywhere else.”