Dawn Hartfield moves on to a role at CPSA

Judith Chrystal - 27 August 2020

She points to research training and leadership opportunities during her time in the department as pivotal to her career trajectory. Back in 2003, Hartfield was at the forefront in the development of two emerging areas: pediatric hospital medicine, and patient quality and safety. With the support and encouragement of the department chair, she completed a master’s in public health to gain research skills and was steered toward administrative training courses at the university to help prepare her for future roles. Though relatively new in her academic career, she took advantage of early leadership opportunities to help guide progress in areas where few structures existed.

Hartfield became a divisional director for pediatric hospital medicine to build that program in Edmonton to what it is today. Local opportunities quickly became national in scope and Hartfield was well on her way to establishing a career in leadership.

“Being in an academic institution also allowed me to have my first role in the area of patient quality and safety, which was chair of the Morbidity and Mortality Committee for the Stollery,” she says. That committee work in an emerging area would become a focus for Hartfield. Her expertise and interest in this field grew, and she received department support for secondments to leadership roles at Alberta Health Services in quality and safety, and involvement with organizations such as the Canadian Patient Safety Institute. She eventually helped to establish a quality improvement structure for the entire zone.

All the while, she continued to teach, conduct clinical research and see patients at the Stollery, although it became a smaller part of her portfolio over the years.

Hartfield capped off her academic career with a promotion to professor in 2020. By that point, she didn’t need the official achievement to build her resume and says that she definitely didn’t need the mountains of paperwork involved! The opportunity to demonstrate leadership by being a role model for others is what pushed her forward.

Hartfield became acutely aware of gender differences in promotion while attending a national physician leadership conference that focused on diversity and inclusion. One of the speakers highlighted the difference between the proportion of female versus male academicians who are promoted. There are far fewer women than men.

What made the push for promotion even more poignant was when Hartfield began to search across the country for professors in her field, necessary to adjudicate her application package. “I’m a pediatrician and most pediatricians are women,” she says. “But there is a paucity of females who are full professors and I thought, ‘Well, that’s disappointing.’”

Another motivator for Hartfield to pursue this milestone was to set a precedent that faculty can be promoted based on medical leadership experience, something that is atypical today.

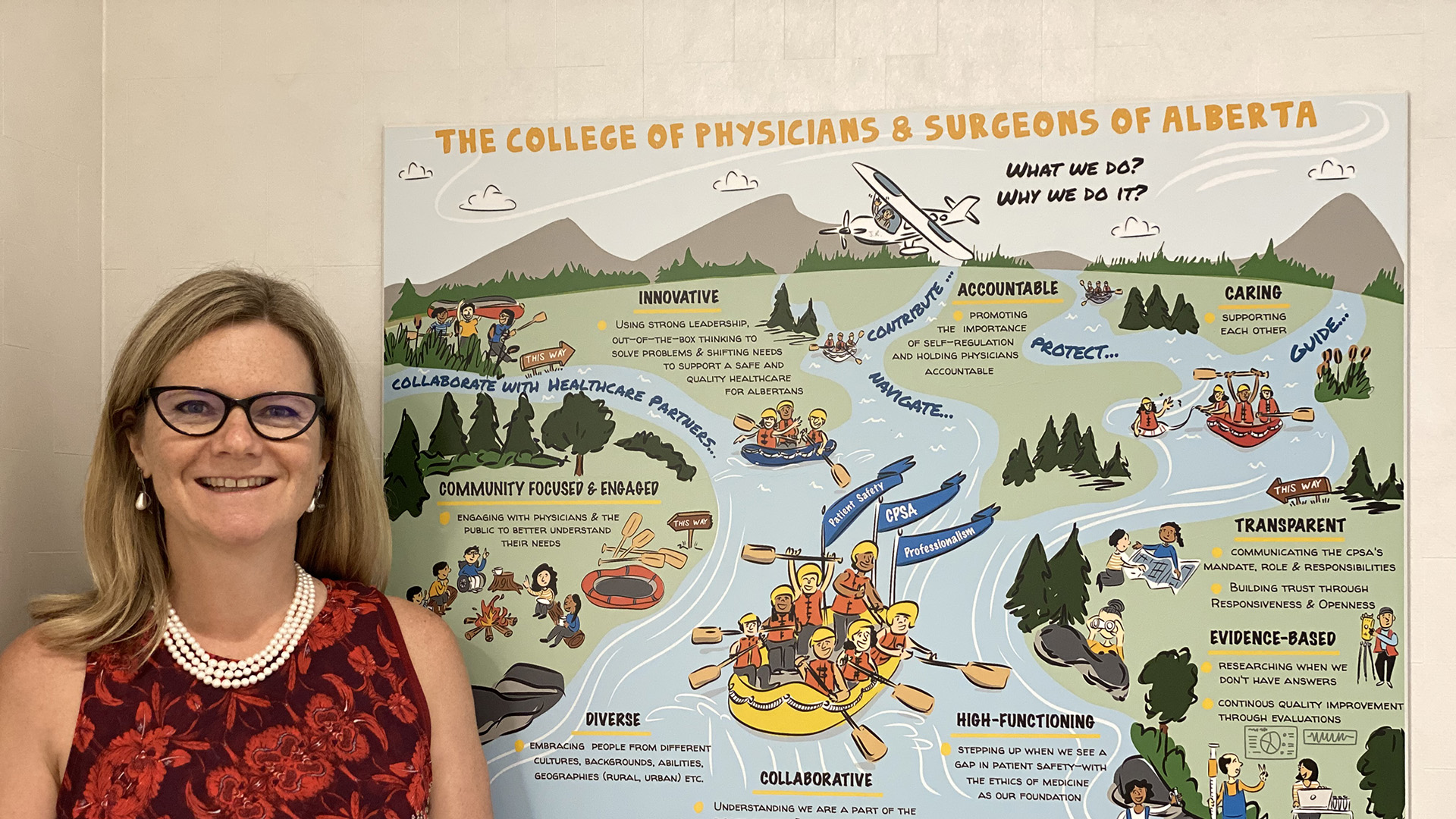

Six months into her full-time position at the CPSA, Hartfield misses seeing young patients at the Stollery and working with the multidisciplinary teams in clinical practice. She also misses teaching learners and interactions with academic colleagues. She hopes to bring a few of those colleagues from the department along to join her at the college and add their expertise to help guide the practice of medicine on a province-wide scale.

Hartfield emphasizes that the competencies and experiences in academic medicine are strengths that she knows others in the department have. “The medical profession is self-regulating so we need people who have a good understanding of things like adult education and evidence-based assessment," she says. "We need those people who are frontline clinicians that understand how the real world is actually working right now regarding the practical aspects of medicine,” she says.

Opportunities to get involved at the college include working groups with very specific mandates, advisory committees that report to council, and council itself. Residents interested in medical leadership can join the team as an elective course.

“If you had asked me if this is what I'd be doing now, I wouldn't have guessed it. But that’s part of the fun because you don’t know where your career is going to go,” she says.