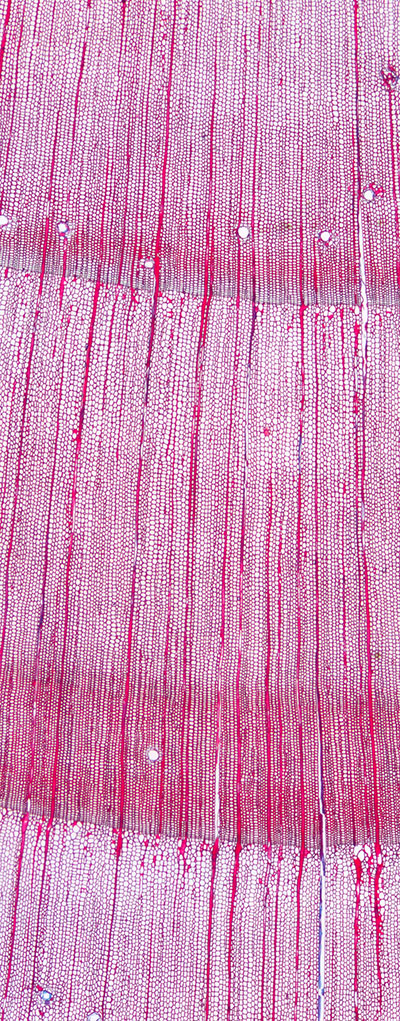

In this stained microsection of lodgepole pine wood, showing its tree rings, the dark red areas show the border between two years' growth rings. Frost damage is visible as blueish and distorted wood cells.

When University of Alberta researchers studied the growth rings of trees that were moved north of their historic growing area in order to escape warming from climate change, they discovered another challenge.

"We found that southern trees are more susceptible to frost events in the fall," said David Montwé, a post-doctoral fellow in the Department of Renewable Resources.

"We think this is because they are genetically pre-programmed for different growing-season lengths. This makes those trees less frost tolerant if a frost hits at the end of the summer."

The result is damage to the trees' wood, which decreases its value, and those points of weakness also make the trees more susceptible to pests and pathogens, said Montwé's fellow researcher Miriam Isaac-Renton, who was a PhD student when their newly published study on lodgepole pine trees was conducted.

Since trees may not adapt to new climate conditions fast enough, some scientists are using "assisted migration," in which seeds are moved toward northern latitudes to both catch up with climate change that has already happened and to prepare for additional warming.

However, there may be unintended consequences of such moves, said Montwé. Working with UAlberta forest geneticist Andreas Hamann and collaborator Heinrich Spiecker, the two researchers decided to look at the effect of frost and the limitations on how far seeds can be moved.

They studied lodgepole pine because it is one of Western Canada's most important timber tree species, and also because it grows in vast parts of the continent, from the Yukon to California, acting as a vital foundation for those areas' ecosystems.

When the researchers also looked at northern trees that were moved to the south, simulating climate warming, they found those trees were more affected by frost in the spring.

"In the north, trees respond to clues in the spring to start growing. If they get the signal of a warm spell, then they start flushing (bursting their buds) and that reduces their frost tolerance," said Montwé.

Unfortunately, those "false springs," defined as early signals of warmth followed by a frost, are happening more often due to global warming, said Isaac-Renton.

"There are two aspects to climate change," she said. "There is warming, but there is also increased probability of extreme weather-droughts and also cold events."

Last year, she said, false springs occurred around the world, resulting in vineyard losses in Europe and orange-crop losses in Florida and Georgia.

While it has been known that long-distance assisted migration scenarios might lead to cold damage, their study found that there are also risks involved under no-intervention scenarios (leaving trees to fend with climate change), as well. The best solution, they said, appears to do assisted migration in some regions but to limit how far those trees are moved.

The study was published this week by Nature Communications.