Celebrating a century of excellence in biochemistry at the University of Alberta

Jennifer Fitzgerald - 24 April 2024

MRC Group in Protein Structure and Function Research Retreat at Westridge Park Lodge, early 1990’s. Bottom row left to right: PI’s Zygmunt Derewenda, Larry Smillie, Charles Holmes, Cyril Kay, Brian Sykes, Bob Hodges, and Michael James

As the Department of Biochemistry celebrates its over-100-year history, we not only commemorate a century of groundbreaking research and discoveries but also pay tribute to many of our notable figures.

Professor Charles Holmes will be one of the featured speakers discussing the rich history of the department at the upcoming 100 Years of Biochemistry conference at the Telus International Centre on May 2 and 3, 2024.

Holmes has intriguing insights into the department's formative years, such as James Bertram Collip's crucial contributions to the Nobel Prize-winning research on insulin, as well as biochemist Cyril Kay’s connection to both Wayne Gretzky and Paul Martin as Order of Canada recipients.

The Roaring Twenties: The dawn of biochemistry at the University of Alberta

The history of the department traces back to the 1920s, but has its roots in the Department of Physiology, which was established in 1914 under Heber Havelock Moshier. During World War I, after Moshier departed for the front in 1916 and was killed in action in 1918, James Collip took over as acting chair. “Collip had begun lecturing in biochemistry since his appointment in 1915 and this led to the department being informally recognized as Physiology and Biochemistry,” says Holmes.

“In 1920, after Moshier's death, university president Henry Marshall Tory appointed Audrey Downs as the new chair, sidelining Collip who had expected the position given his leadership since Moshier's departure,” states Holmes. “To mend their relationship, in 1921 Tory arranged for Collip to have a Rockefeller Travelling Fellowship to collaborate with Banting and Macleod in Toronto, promising him the chairmanship upon his return to Edmonton.”

This move positioned him alongside Frederick Banting and Charles Best under John Macleod's supervision. Their collaborative efforts on the insulin project, which Collip significantly advanced by enhancing its purification process, marked a pivotal moment in treating diabetes; transforming it from a fatal disease to a manageable condition.

“Despite his crucial contributions, Collip was overlooked when the 1923 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was awarded to Banting and Macleod. However, both Nobel laureates acknowledged their colleagues' efforts by sharing their prize money with Best and Collip respectively,” says Holmes.

Collip’s research not only positioned the U of A as a leader in medical science but also paved the way for future innovations. Collip’s later discovery of parathyroid hormone (PTH) furthered the department's pivotal role in understanding critical physiological processes. “This hormone, critical for calcium regulation in the body, was identified by Collip during his research on the glands of the endocrine system,” says Holmes. A plaque in the U of A’s Medical Sciences Building, installed in the 1960s, commemorates this achievement.

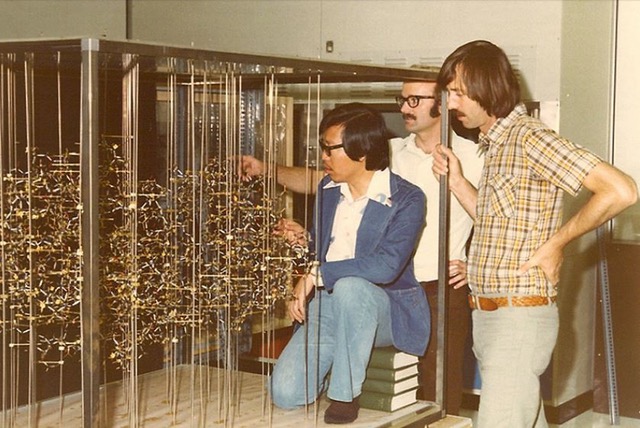

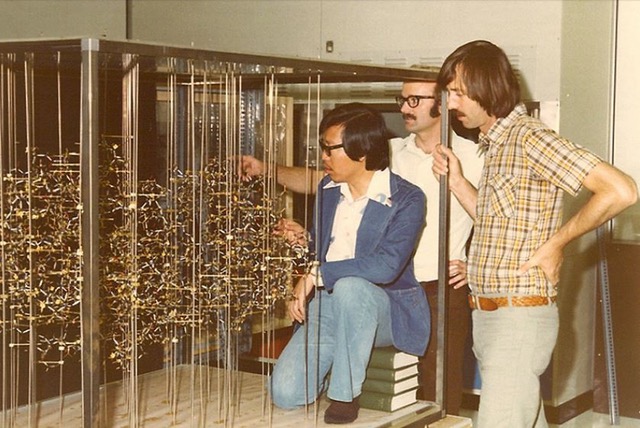

Michael James and researchers show off their X-ray crystal structure of Streptomyces Griseus Peptidase B (SGPB), the first 3D protein structure to be determined in Canada.

Brian Sykes delivers an engaging lecture at the Faculty Club, sharing his expertise with audience.

Foreground: U of A alumnus Lewis Kay in earnest discussion with Brian Sykes. Background: Cyril Kay conferring with Charles Holmes and Mark Glover, Larry Fliegel with fellow members of the Department of Biochemistry.

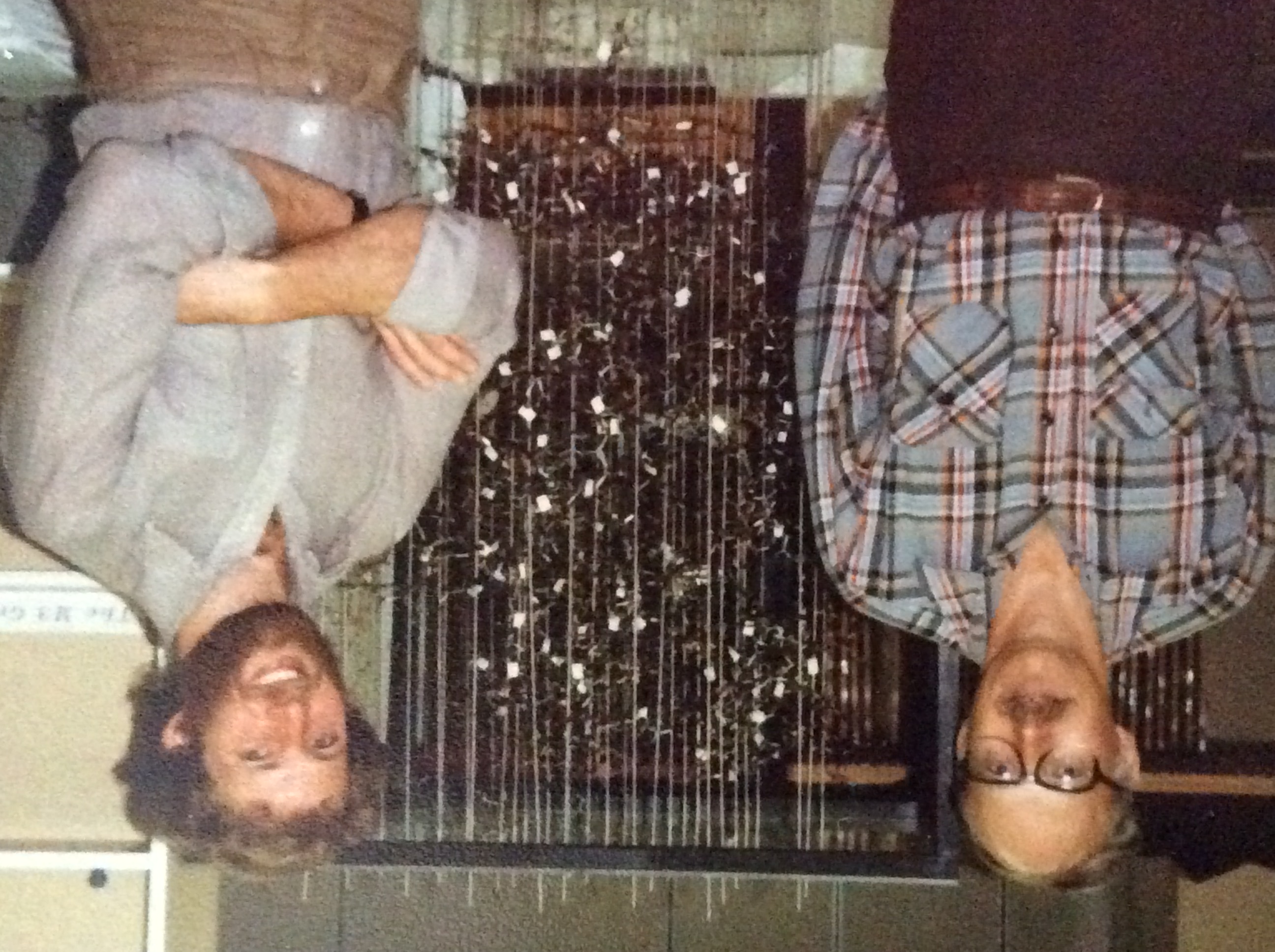

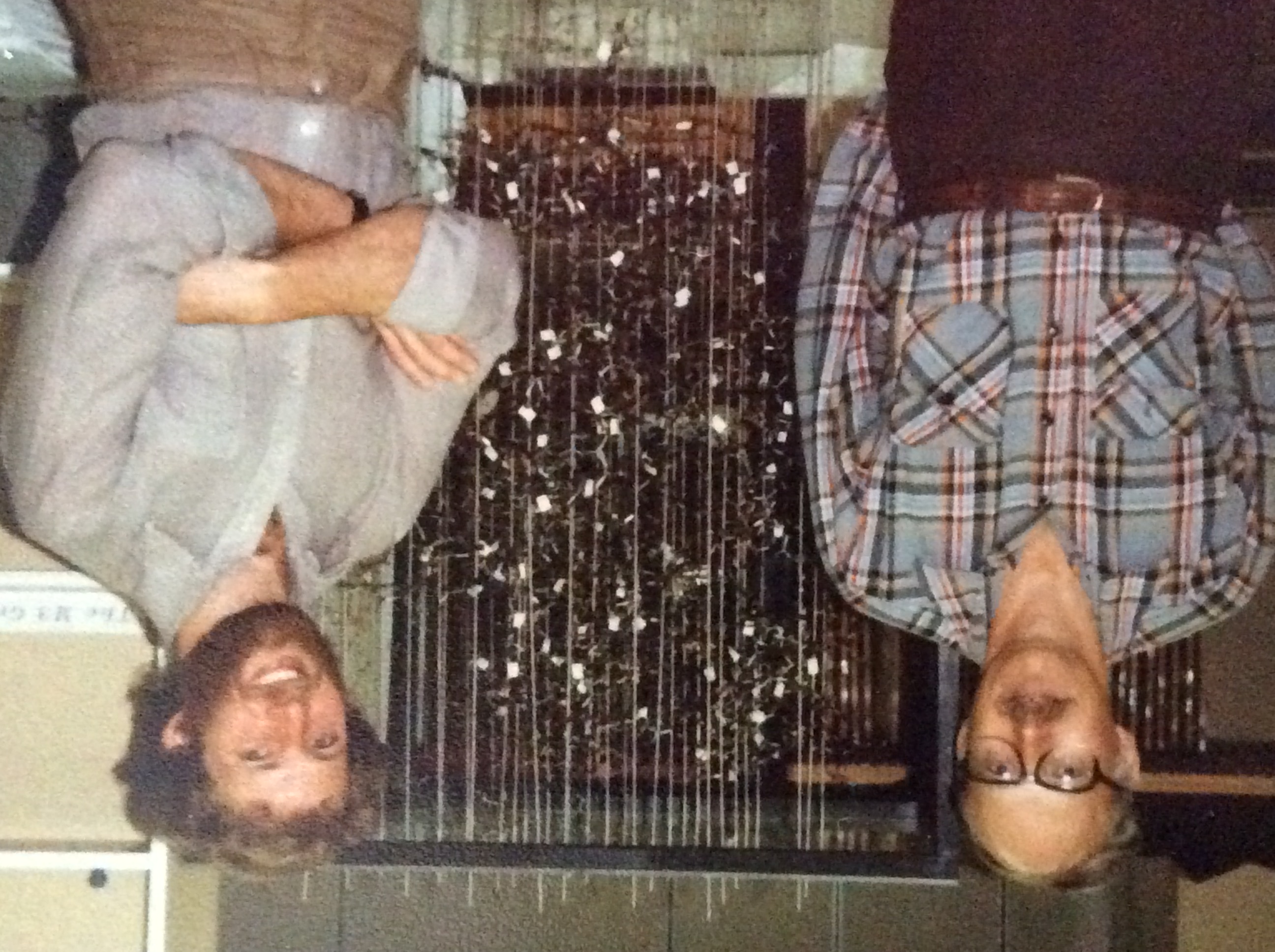

Neil Madsen (left) and his postdoctoral fellow Steve Withers (right), standing before the molecular structure of glycogen phosphorylase, the key catalyst in glycogen breakdown.

Marek Michalak wins the University Cup in 2013, celebrating with Dean FoMD Verna Yiu and Chair of Biochemistry Charles Holmes.

Transitional challenges and renewed focus

During the mid-1900s the biochemistry department saw a redirection towards more practical scientific endeavours, with a focus on “nutritional biochemistry influenced by the socio-economic conditions of the Great Depression and World War II,” says Holmes.

Under the direction of biochemist Cyril Kay, who was appointed by chair Bruce Collier in 1958, the department not only grew in stature but also made significant scientific contributions.

Both Kay and Larry Smillie ushered in a new era of research excellence, particularly in protein structure and function. This period aligned with the discovery of the DNA double helix and the burgeoning interest in genetic and protein research. “Their efforts were so groundbreaking that their work led to the formation of the first Medical Research Council Group in Protein Structure and Function, bringing substantial research funding and prestige to the U of A,” says Holmes.

John Colter’s legacy in shaping a premier biochemistry department

In 1961, the appointment of virologist John Colter meant the department continued to flourish. He served as professor and chairman of the department until 1987. According to Kay, “His most important legacy was building the premier department of biochemistry in Canada and certainly one of the best in North America.”

Colter expanded the department's research and ensured new hires collaborated with the established team, creating a cohesive environment without cliques.

Colter was renowned for mentoring young faculty and transforming manuscripts into clear successful papers and grant applications with his exceptional writing skills and patience.

Michael James and researchers show off their X-ray crystal structure of Streptomyces Griseus Peptidase B (SGPB), the first 3D protein structure to be determined in Canada.

Trailblazers in biochemistry

Under this unmatched level of collaboration, the department was establishing world-class scientists under Kay such as Michael James, renowned for his pioneering work in crystallography and Brian Sykes, who specializes in structural biology, nuclear magnetic resonance studies and human muscle protein research.

James was the first protein crystallographer in Canada, and made many seminal discoveries in this area, in addition to training a whole generation of Canadian crystallographers. Some of James’ seminal discoveries include elucidating the structures of key protease enzymes in critical human pathogens (including COVID), the discovery of the mechanism by which penicillin and related antibiotics are broken down by antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and structures of toxins from pathogenic bacteria.

Brian Sykes delivers an engaging lecture at the Faculty Club, sharing his expertise with audience.

Over Sykes’ illustrious career, he significantly advanced our understanding of the molecular mechanisms of muscle regulation through his groundbreaking studies on the protein troponin. His research has led to profound impacts in fields ranging from basic biology to clinical applications in heart disease.

“He has authored 480 peer-reviewed articles and has been recognized as one of the most prolific biochemists by the journal Biochemistry,” Holmes says.

Legacy of scholarly excellence and distinguished honours

Holmes highlights the department's prolific output, mentioning that “between 1974 and 1995, the MRC Group produced 1,600 papers in leading international biochemical journals.”

Foreground: U of A alumnus Lewis Kay in earnest discussion with Brian Sykes. Background: Cyril Kay conferring with Charles Holmes and Mark Glover, Larry Fliegel with fellow members of the Department of Biochemistry.

The Department of Biochemistry is proud to have several distinguished dignitaries among its ranks. Kay, Sykes and James are recognized as Officers of the Order of Canada, one of Canada’s highest honours. Kay is also celebrated as a member of the Alberta Order of Excellence. Kay, Smillie, Sykes, James, Bob Hodges, Bruce Collier, Bill Bridger, John Colter, Ron McElhaney, David Brindley, Joel Weiner, Neil Madsen, Carol Cass, Dennis Vance, Chris Bleackley and Marek Michalak have been acknowledged as Fellows of the Royal Society of Canada, a testament to their significant scientific impact. Furthermore, Sykes and James have earned the prestigious status of Fellows of the Royal Society of London, given their influential work on an international scale, and Robert Fletterick of the MRC group is a member of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences.

Neil Madsen (left) and his postdoctoral fellow Steve Withers (right), standing before the molecular structure of glycogen phosphorylase, the key catalyst in glycogen breakdown.

Advancing protein research

The MRC group's research now extends to viral proteins, where their structural studies led to the creation of highly selective enzyme inhibitors. This line of inquiry is being advanced by Joanne Lemieux, who is focusing on specific inhibitors for the COVID protease.

Other significant findings include the first structure of the breast cancer protein BRCA1 by Mark Glover, studies in RNA biochemistry, and insights into antibiotic resistance through the structural analysis of beta-lactamases and their inhibitors. Their work also encompasses proteins involved in DNA damage, cancer biology and membrane protein structures.

From 2010 to 2020, Holmes himself chaired the department, a period marked by expansion and enhanced research capabilities. Under his leadership, the department solidified its reputation for excellence in protein structure research.

Marek Michalak wins the University Cup in 2013, celebrating with Dean FoMD Verna Yiu and Chair of Biochemistry Charles Holmes.

A new era of advanced technologies

Looking forward, Holmes says the department, under the leadership of chair Mark Glover, is on the cusp of another transformative period with recent funding for advanced research technologies like cryo-electron microscopy. “This method will allow scientists to visualize large protein structures at atomic resolution, significantly advancing our understanding of molecular biology and facilitating the development of new therapeutic strategies,” says Holmes.

In cancer biology, combining multi-omics analyses with new animal and tissue models is revolutionizing our understanding of tumour-environment interactions. This integration is key to developing targeted, effective and less-invasive cancer therapies.

The department is also expanding into systems biology, proteomics and computational biochemistry. Leveraging advancements in high-throughput technologies — such as artificial intelligence and machine learning — is enhancing our ability to quickly and accurately analyze vast biological data and accelerating discoveries in biomedical research.

Empowering future leaders in biochemistry

The department remains committed to cultivating an environment where current students and future biochemists can thrive and contribute to its rich legacy.

“Graduates of the department have consistently moved on to prestigious positions and opportunities worldwide, including full scholarships at Oxford, Cambridge and top U.S. universities like Stanford and Harvard,” he says.

The department's reputation, built on decades of innovative research and teaching, opens numerous doors in health sciences. It equips students not only with technical knowledge but also with the critical thinking skills necessary to excel in diverse careers. “I think biochemistry is a particularly important area to be able to allow students to develop their creativity, their ability to ask questions and challenge dogma,” says Holmes.