Alumni spotlight: Celebrating Aleksandar Kostov

18 October 2023

Aleksandar Kostov posing with a robotic arm. Photo supplied.

Today, terms like “machine learning” and “artificial intelligence” are becoming commonplace, but there was a time in the nineties when they were on the fringes of understanding. At the forefront of exploring these new technologies was Aleksandar Kostov at the University of Alberta, who delved into pioneering research in biomedical engineering and neuroscience. His groundbreaking work on brain-computer interface and machine learning not only showcased his dedication in the field but also his profound commitment to bettering the lives of those he served.

His daughter, Sanja Kostov, an assistant professor and physician in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, recalls family stories of her dad spending countless hours tinkering with the earliest versions of computer software and hardware.

“My mom tells stories of him driving to Germany in the mid-80s to buy Commodore 64 parts because they weren't available in eastern Europe. He was one of the few at that time who had the expertise to assemble a computer in his hometown of Belgrade, Yugoslavia,” says Sanja.

Aleksandar Kostov went on to complete a PhD in biomedical engineering through the Division of Neuroscience in 1995 at the U of A. He belonged to the very first cohort of graduates from the university's neuroscience graduate program and was the first graduate of the program. As an assistant professor in the Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine, Kostov's career soared as he embarked on research with a central focus: to enhance the quality of life for people with spinal cord injuries. Shortly after his appointment, he established the Laboratory for Advanced Assistive Technologies and recruited students from around the world.

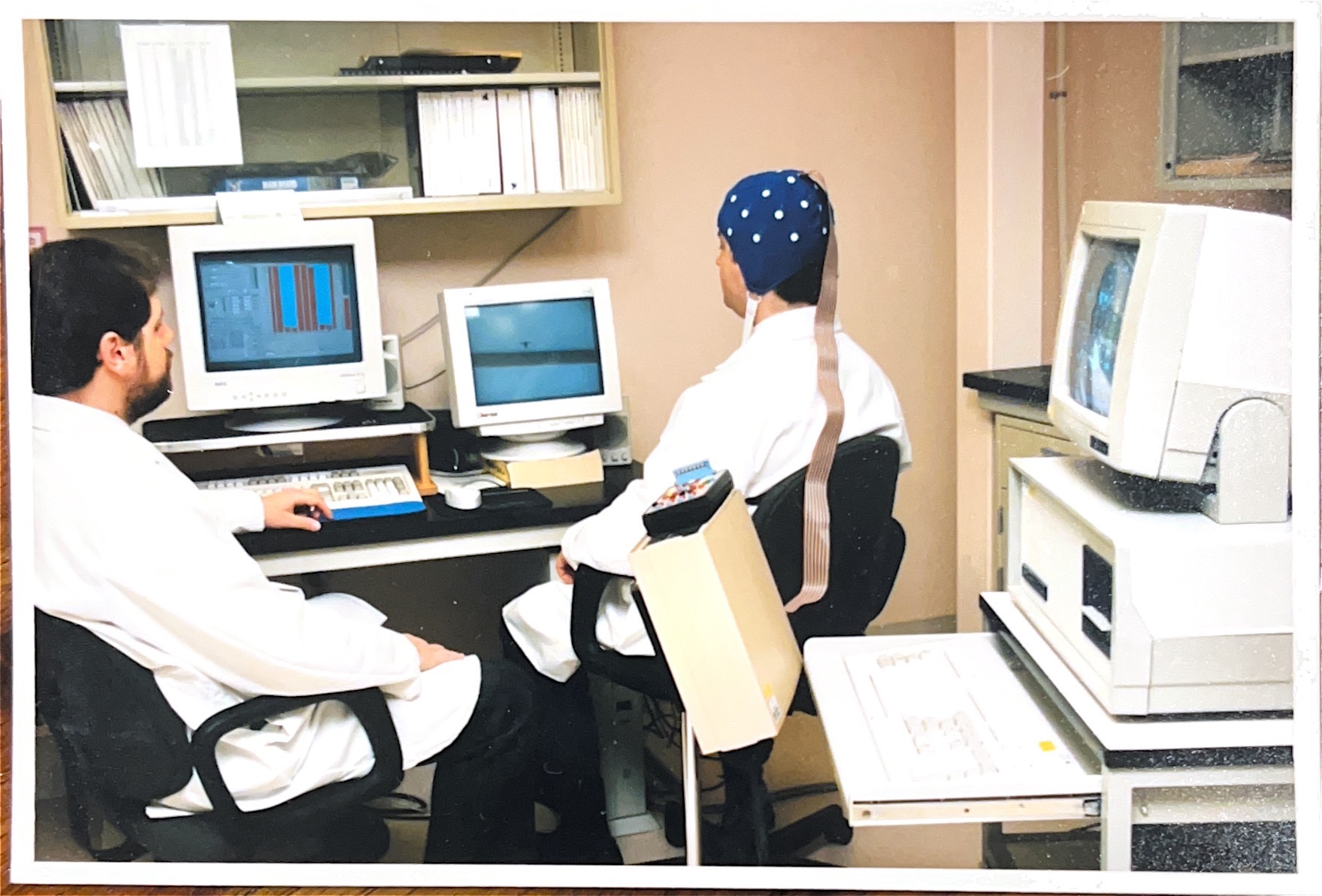

His pioneering work, referred to as “Dr. Kostov’s mind-reading machine,” was the development of technology that enabled the control of a cursor on a computer screen by isolating specific brain waves. In the mid-1990s, he was among a handful of individuals worldwide working in this area. This technology aimed to help individuals with spinal cord injuries and conditions like amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) regain functional freedom through mental activity. His innovations in brain-computer interface and machine learning were widely recognized, and his advancements contributed significantly to this burgeoning area of study.

Sanja says her father once explained to her how this software worked when she was a teenager.

"Imagine that you're at a football game and everyone is cheering. You're at one end of the stadium and you see a person opposite you in the stands. They're shouting something too and you want to know specifically what they're saying. This computer’s job is to isolate only their shouts so you can hear them, and then learn to help you isolate their shouts better in the future,” she says.

Kostov not only collected data but he also "collected friends, many of whom were people in wheelchairs,” Sanja remembers fondly. “He deeply cared about improving the lives of people with disabilities,” she says.

“Consider a patient who has suffered such a severe spinal cord injury that they can't voluntarily move any part of their body,” says Sanja. “In some extreme cases, their only form of movement might be a blink. For those who can't even manage that, their ability to function and interact with the world becomes nearly nonexistent. Imagine equipping such individuals with technology that allows them to control machines using only their thoughts. This would reintegrate them into society, enabling movement and communication.”

“That was the ultimate vision of my father. While the initial technology being developed wasn't precisely there yet, the mere capability to reliably discern thought patterns was groundbreaking for its time,” she explains.

It was this groundbreaking research that garnered him the Canadian Information Technology Innovation Award in 1998. This prestigious accolade is usually bestowed on large companies – Blackberry won two years later – showing the significance of his work just three years into his post-doctoral journey. He received letters from the Minister of Justice and Attorney General and the mayor of Edmonton praising him for his innovative approach to enhancing the lives of people with disabilities.

Life's unpredictable twists however presented formidable challenges. At age 41, Kostov was diagnosed with a rare blood disease called myelodysplastic syndrome – a condition in which bone marrow doesn't produce enough blood cells – necessitating an urgent bone marrow transplant.

Thanks to the financial assistance and unwavering support of family, friends and colleagues at the U of A, he underwent successful treatment. However, a stroke, caused by complications he developed from an infection while on immunosuppressants, tragically shortened his life. The Kostov family expresses profound gratitude for every gesture of support, whether it was financial support for his treatments or letters penned to the government advocating on his behalf. This was especially significant when his treatment, deemed "experimental," wasn't covered by Alberta's health care system at the time.

After his untimely passing in 2000, his family and colleagues remember Kostov for his innate humanity. He wasn't just a scientist; he was a compassionate individual who genuinely cared about improving the lives of those he served.

“The gold starfish pin he proudly wore on his lapel reflected his philosophy – you may not be able to help everybody but if you can help even one person it's worth doing,” recalls Sanja.

Kostov's legacy isn't just confined to his innovative research or the awards. Above all, he cherished his family (wife, Ibojka and daughters, Sanja and Jelena), and when asked he would say his children were his proudest achievement. Now, as the torch is carried forward by his family, with his legacy living on at the U of A, it is our collective duty to ensure that the contributions of Kostov are not only remembered but celebrated.

Kostov was and still is a beacon for the Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine. His office in Corbett Hall still bears a plaque nearby with a poem penned by his daughter in her teenage years. In the basement of the I CAN Centre for Assistive Technology at the Glenrose Hospital, a photo of Kostov graces the wall there, a tribute to the research group he spearheaded.

He was not only a brilliant scientist and biomedical engineer tackling some of the toughest challenges, but at the U of A he is remembered as a cherished friend, colleague and mentor. Though he may have passed too soon, his groundbreaking work remains. His mission was to change our perspective on disability. He believed the real problem wasn't with the individual, but with the world around them. And he was set on changing that world for the better.