Vice-dean of research receives almost $1 million in CIHR funding

Shirley Wilfong-Pritchard - 15 August 2023

Richard Lehner

Richard Lehner is vice-dean of research at the University of Alberta Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry’s Office of Research, professor in the Department of Pediatrics and adjunct professor in the Department of Cell Biology, and member of a research team called The Group on Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids. His research project entitled Regulation of hepatic fat synthesis, turnover and transport by arylacetamide deacetylase (AADAC) has recently been awarded a hefty five-year grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). The funding may lead to the development of novel drug treatments that target issues of fat accumulation and inflammation in the liver.

We caught up with Richard Lehner to find out more about his research and the impact of this recent funding. We also learned how to improve one’s chances of writing a successful grant application.

What is your research about and how might it benefit the larger community?

For the past 25 years or so my group has been researching various aspects of fat metabolism, in particular the processes regulating fat absorption by the intestine, secretion of fat into the bloodstream and storage of fat particularly in the liver, which is the subject of the research project funded by CIHR.

Accumulation of fat in liver cells is called steatotic liver disease (SLD) and this condition is a major health problem. SLD affects about 30 per cent of the adult population and over 70 per cent of people with obesity, making SLD the most common chronic liver disorder. The health risk for people with SLD is that this disease can progress to more serious problems including inflammation and swelling of the liver, called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH); normal liver tissue being replaced by non-living scar tissue, called cirrhosis; and end-stage liver disease and liver failure, the most common reason for needing a liver transplant. Having SLD or MASH also places people at greater risk for Type 2 diabetes, heart disease and end-stage kidney disease. Today, we still have no effective treatments for MASH.

Recently, we discovered that a protein called AADAC regulates liver fat storage. We found that AADAC degrades fat to simpler molecules called fatty acids that can then be used for energy production and other functions in the cell. When we reduced the amount of AADAC in the liver, this led to the development of fatty liver, insulin insensitivity and weight gain, suggesting that AADAC may play an important role in liver fat metabolism.

Our proposed research aims to find out how AADAC regulates liver fat production and storage. A better understanding of how AADAC works may lead to the identification of new potential drug targets for treatments for SLD/MASH and diseases triggered by liver fat accretion.

What will receiving almost $1 million in project grant funding mean to your research?

We have several aims to tackle over the next five years. AADAC amounts are significantly lower in the livers of obese, insulin-resistant people. Interestingly, decreased amounts of liver AADAC is also observed in laboratory animal models of obesity. So, one objective is to assess whether restoration of AADAC in the liver would correct liver fat storage, reduce body weight and improve insulin sensitivity.

Initially, we will use genetic means to restore AADAC in the models of obesity but the hope is to also understand how AADAC amounts in cells are regulated because this could potentially lead to developing therapeutic approaches.

We have observed that liver cells lacking AADAC present with abnormal size and organization of the key cellular energy-producing unit, the mitochondria. These mitochondria show increased interaction with fat droplets that accumulate in AADAC-deficient livers and with an organelle that supplies calcium to mitochondria, called endoplasmic reticulum. This cellular disorganization due to AADAC deficiency suggests compromised oxidative capacity of the cell and we have planned experiments to investigate how AADAC regulates energy metabolism.

Finally and interestingly, liver cells without functional AADAC start making more fat, which further augments liver fat accumulation. We would like to better understand how AADAC keeps fat synthesis in check.

Where do you hope your research will be in five years?

In five years I hope we will know the precise functional role of AADAC. This is a discovery research project. It may turn out that AADAC is not a suitable therapeutic target to mitigate SLD/MASH but we will still generate new knowledge about fat metabolism.

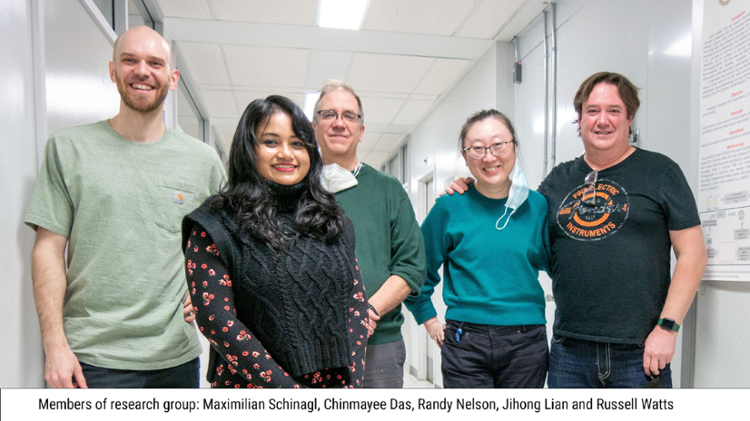

Who is working with you on this project?

This has been and will remain a team research project. The initial research findings on which the project is based have been generated by a team including a research associate (lead), graduate students, postdoctoral researchers, undergraduate students, technologists and faculty members.

While my group has significant lipid metabolism expertise, additional critical expertise was required to generate research data. In particular, this included collaboration with the groups of Dr. Rene Jacobs and Dr. Donna Vine from the Faculty of Agriculture, Life & Environmental Sciences, Dr. Robin Clugston from the Department of Physiology and Dr. Aducio Thiesen from the Department of Laboratory Medicine & Pathology.

For future studies we have contacted a mitochondria expert in the Department of Cell Biology, Dr. Thomas Simmen, whose expertise in calcium transport between endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria will be invaluable to deliver on one of our aims.

Can you comment on the role the core facilities play in your research and the overall success of the faculty?

We couldn’t deliver on past and proposed research programs without the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry-supported core research facilities.

Health Sciences Laboratory Animal Services (HSLAS) support is critical for our in vivo research where we study fat absorption in the intestine, storage in various organs and transport in blood. We heavily rely on expertise in the Lipid Analysis Core and the Cell Imaging Core. These cores contain state-of-the-art infrastructure that would be impossible to manage in a single laboratory.

Most importantly, the cores are staffed with experts who ensure my trainees are well trained using the infrastructure and also provide suggestions for experiments so the data are reproducible and high quality.

The core research facilities have evolved over the past 15 years. At present, there are seven such facilities. Over the past year, they supported more than 500 users from nine U of A faculties and nine external groups. Over 50 per cent of the users are graduate students who have an amazing opportunity to train on and use the latest technologies.

Access to core facilities is subsidized by the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry with an average subsidy of just over 50 per cent, so researchers not only benefit from access to equipment and expertise from core staff but at less than 50 per cent of operational cost. HSLAS operates at a similar subsidized rate. Importantly, there are no differential fees for other U of A faculties, which facilitates cross-faculty research collaborations.

As vice-dean of research, professor and part of a research team, not to mention being a member of multiple committees and boards and a mentor to students, how do you balance research with your teaching and leadership responsibilities?

That is a good question and I am not sure balance would be an appropriate term. My position is 40 per cent research, 50 per cent administration and 10 per cent teaching, but in the past two to three years with COVID, university restructuring and budgetary challenges, the overwhelming majority of my time has been spent on administration.

I am fortunate that my laboratory has received research funding from CIHR, NSERC, Heart & Stroke of Canada and Cancer Research Society. This meant I was able to retain senior research staff in my laboratory who have not only carried out high-quality research but assisted in training students.

I enjoy teaching, but my teaching allocation does not allow me to spend a lot of time in the classroom. I teach one-third of a course on lipid metabolism offered by the Department of Physiology with the rest being taught by my colleagues from The Group on Molecular and Cell Biology of Lipids.

I am at a stage of my career where I feel it is time to give back, to provide an environment that would help others succeed. This is why much of my focus is on core research facilities, shared facilities and grant success. I have to state that the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry Office of Research is staffed with dedicated individuals who make a fantastic team.

The faculty has successfully applied for 10 project grants from CIHR this spring, resulting in over $8 million in funding. Can you comment on the importance of this?

Although CHIR accounts for less than 25 per cent of total research funding in the Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, its importance cannot be overstated. CIHR is a key national peer-review agency funding health research. Obtaining funding from CIHR is not easy since the success rate has fluctuated between 15 - 20 per cent over the past five years.

I believe that every research-intensive faculty member with at least 40 per cent time protected for research should successfully compete for CIHR funding if their research fits the CIHR mandate, but the university, College of Health Sciences, faculty, institutes, departments and research groups have to provide a supportive environment to enable success. This means researchers should be afforded time to focus on what they do best — research.

There have been far too many distractions over the past few years due to reorganization and budget cuts and researchers are now burdened with excessive administrative duties. Hopefully, we can resolve this issue soon because CIHR (and other Tri-council) funding is very important not only for the individual researcher but for the university and faculties.

CIHR, NSERC (Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council) and SSHRC (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council) funding determines the amount of overhead (Research Support Fund) allocated to universities. Tri-council funding is also used in Canada Research Chair allocation, a program to recruit and retain top research faculty.

Finally, Tri-council funding is a key determinant for the Canada Foundation of Innovation (CFI) allocation. This program provides 40 per cent of funding for research infrastructure, with the other 40 per cent coming from the Government of Alberta and 20 per cent from other sources. Without CFI, there would not be operational core research facilities or HSLAS.

Were any applications not successful?

Unfortunately, yes. Our faculty is usually on par with the national success rate, which fluctuates between 15 to 20 per cent. In some competitions, we fared better than the national average and in some, we were slightly below.

There are indicators that internally reviewed applications are more successful and applications that have received editorial assistance have had an increased success rate. I have never applied to CIHR without having it internally reviewed by colleagues with high and medium/low expertise in the research area. This is what CIHR committee membership is — applications are mainly reviewed by peers with medium expertise and only sometimes with high expertise. So the applications need to be written with this in mind — they should be written for the reviewer, not for the applicant. In other words, applications should be readable and understandable by peers with medium expertise in the research area.

How difficult or time-consuming is the application process?

CIHR applications, especially new ones, take a significant amount of time to prepare. I would estimate at least two months full time (300-plus hours). The application process involves going over research concepts/relevance, poring over the most recent literature to provide an up-to-date background of where the research field is at, getting experimental ideas down on paper, communicating with collaborators/co-applicants, writing/revising, etc.

Re-submission of unsuccessful applications may take a little less time, but one still needs to take into account issues raised by reviewers, possibly generating additional preliminary data to support the research aims.

Do you have any advice for other researchers looking to apply for project funding?

My advice would be to start early. Focus on one application at a time (no dilution of focus/time). Choose internal reviewers who would be supercritical (constructively) with a mission to find holes and “destroy” the application. I know this may sometimes be hard to accept by faculty members who have been successful in carrying out independent research, but if an internal reviewer identifies issues, it is not that the internal reviewer just did not get it, it is because the applicant did not explain it well enough for the reviewer to get excited about the project.

I thought I wrote a really good application before I got comments from my internal reviewers. They found several fairly serious issues in the application and provided constructive feedback. I believe that without this internal peer review and changes to the application I made based on the reviewers’ suggestions, my application might not have been successful.