Newly appointed Canada Research Chair Hongbo Zeng is making polymers stick to contaminants at the molecular level.

(Edmonton) University of Alberta engineering professor Hongbo Zeng has been named the Canada Research Chair in Intermolecular Forces and Interfacial Science, a prestigious appointment that will bring $200,000 per year for the next seven years to the university. His fundamental research--including studies he is conducting for Future Energy Systems in the area of non-aqueous extraction of hydrocarbons--could vastly improve cleanup technologies related to the oil sands industry.

Facilitating a molecular handshake

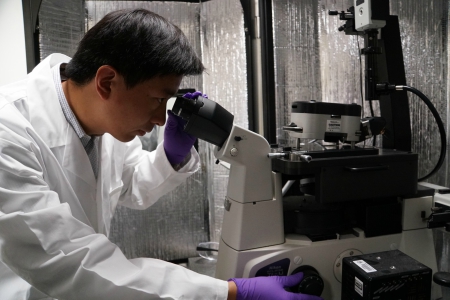

Zeng studies polymers at the molecular level, examining their surfaces at the nano scale in order to understand how they interact with different types of particles. His lab can also customize polymers, making it easier for them to stick to certain types of contaminants.

"It is difficult to shake hands with someone if you both offer closed fists," Zeng explains. "You can think of the surface of a molecule like a hand, and we search for molecules that have compatible open hands so they can hold onto each other."

Historical research in this area was often conducted by trial and error--mixing two agents together and seeing what happened--but by studying the molecular surface, Zeng and his students can identify compatibility under a microscope, reducing time, waste, and cost.

Zeng says this fundamental research can have many applications.

Cleaning the bitumen, and the tailings

When molecules stick together, they become larger and easier to filter out of liquids. This is especially important when removing contaminants from oil sands bitumen, and also from tailings ponds.

In oil sands bitumen, asphaltenes, which are particles of asphalt similar to that used in road construction, often collect at the points where oil and water meet. Flushing them out at an industrial scale is energy-intensive and requires large amounts of clean water. In his work for Future Energy Systems, Zeng is exploring the use of polymers to weigh down asphaltenes, so that they can be removed without water, potentially eliminating a key element of oil sands waste.

Cleaning the bitumen is only one potential application. With the methods and data developed to tackle asphaltenes, Zeng expects polymers can be customized for numerous types of cleanup.

"Tailings pond slurry is water with contaminants suspended in it," he explains. "These particles are not dense enough to sink to the bottom, so for instance when ducks land in what they believe is clean water they are covered in contaminants and die."

Zeng believes selected polymers can tackle this problem, potentially helping those contaminant molecules clump together and sink in order to accelerate cleanup.

The study of intermolecular interactions will have numerous applications throughout the energy sector, both eliminating sources of waste and assisting with the cleanup of already-contaminated sites. Through his Canada Research Chair, Zeng will continue to contribute valuable research to challenges in this area, and to problems and opportunities beyond.