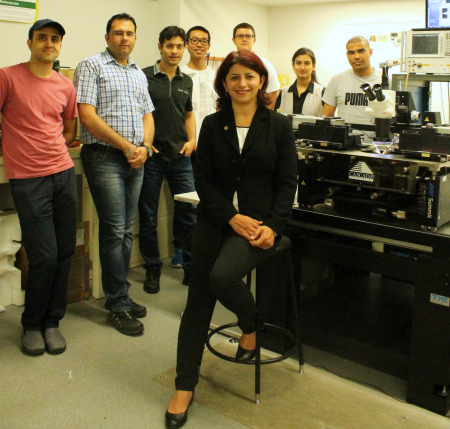

Mojgan Daneshmand, seen here with her research group, has won a prestigious international award from the IEEE: the Lot Shafai Mid-Career Distinguished Achievement Award. The honour recognizes her pioneering contribution to microwave and millimetre wave technologies and being a role model for women in engineering.

(Edmonton) An electrical engineering professor and Canada Research Chair holder has won a prestigious international award for her exceptional research and for establishing herself as a role model in engineering.

Mojgan Daneshmand, who holds the Canada Research Chair in Radio Frequency Microsystems for Communication and Sensing has won the IEEE Lot Shafai Mid-Career Distinguished Achievement Award. The honour recognizes her pioneering contribution to microwave and millimetre wave technologies and being a role model for women in engineering.

Daneshmand and her colleagues in the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering were first to establish modern microwave characterization labs at the U of A.

"We have a lot of micro/nanofabrication facilities, which helps me," she said. "But when I came here, we didn't have any microwave facility. I worked with the colleagues, and now we have a good microwave facility."

Daneshmand's research is multidisciplinary and has numerous applications in communication technology, oil sands, and biomedical industries. One of the devices she developed is a non-invasive non-contact microwave sensor for conducting real-time monitoring of physical and chemical properties of substances. The process eliminates the time required to run lab tests to classify a material or chemical, and determine its concentration or consistency.

"It's a very small sensor, it can be 2 cm by 2 cm or even smaller, which you put in proximity to a chemical. The device is sitting outside, it's not contaminating anything, it's not interacting with any processes," said Daneshmand.

Another big chunk of her research has to do with designing integrated millimetre-wave communication devices for cell phones and satellites. As information traffic is expected to get heavier, communication companies are looking closely at using a wider range of frequencies and higher bandwidth to avoid "traffic jams" in their networks.

"Lower bandwidths are full now," she said. "Millimetre waves are more accessible, but we don't have the technology yet, so that's the area we're researching."

Among possible future applications of Daneshmand's research are sensing devices for biomedicine.

"If you have a blood sample, the sensor could potentially tell you its parameters," she said. The biggest potential advantage is that monitoring and analysis could be done in-situ, with no needles or tubes.

Daneshmand credits the university for the freedom to choose the field to work in.

"I really like what I do, that's one thing. The second thing is that the university is a good environment, they don't tell you what to do, they let you grow yourself so that you start figuring out what you like to do and become good at it," says Daneshmand, adding that the research groups she leads have always been supportive.

Most importantly, her family has always been supportive of her career as an academic, researcher, professor, and an inspiration for young engineers.

"I've always had a good family support, either from my parents, my husband, or even my kids," says Daneshmand.

As a role model for women in engineering, Daneshmand motivates students and colleagues to embark on ambitious projects and never surrender in the face of a challenge.

"It's joyful-it's not hard. If you like it, you'll do it", Daneshmand says of being an empowering woman in engineering.