A conversation with Christina Isajiw about her impactful memoir

5 November 2024

At this time when Human Rights across the world are more precarious than ever, we reflect on Christina Isajiw’s impactful book, Negotiating Human Rights: In Defence of Dissidents during the Soviet Era. A Memoir. With passion and a novel perspective, Ms. Isajiw uses her first-hand experience working in defense of human rights in the years following the Helsinki Accords to shed light on a tumultuous period of Ukrainian history.

Our latest article features a conversation with Christina Isajiw about her book, and her experiences.

A conversation with Christina Isajiw about her impactful memoir

Sophia Isajiw, HREC Assistant Director of Education and CIUS Research Associate

I grew up helping my mother stuff envelopes with news releases, copy editing and filing documents. This put me in a unique position to interview her for a deeper insight into the writing of her historic memoir.

Christina Isajiw is a former director of the Human Rights Commission of the World Congress of Free Ukrainians (WCFU, today the Ukrainian World Congress). She spent over 25 years during the 1970s, 1980s, and into the 1990s lobbying in defense of Ukrainian dissidents and human rights activists in the USSR and post-Soviet space within the context of the Helsinki Process. The 1975 Helsinki Accords initiated a unique international instrument among the signatories, linking security and respect for human rights, fundamental freedoms and equal rights, and self-determination of peoples; the Soviet Union had endorsed the accords and could thus be pressured to abide by them. Isajiw’s memoir Negotiating Human Rights: In Defence of Dissidents during the Soviet Era (2014) chronicles the role of the “Helsinki network”—NGOs on both sides of the Iron Curtain—which maintained pressure on Western politicians to keep human rights on the agenda of disarmament and other strategic negotiations and contributed to the democratization and ultimate fall of the Soviet Union.

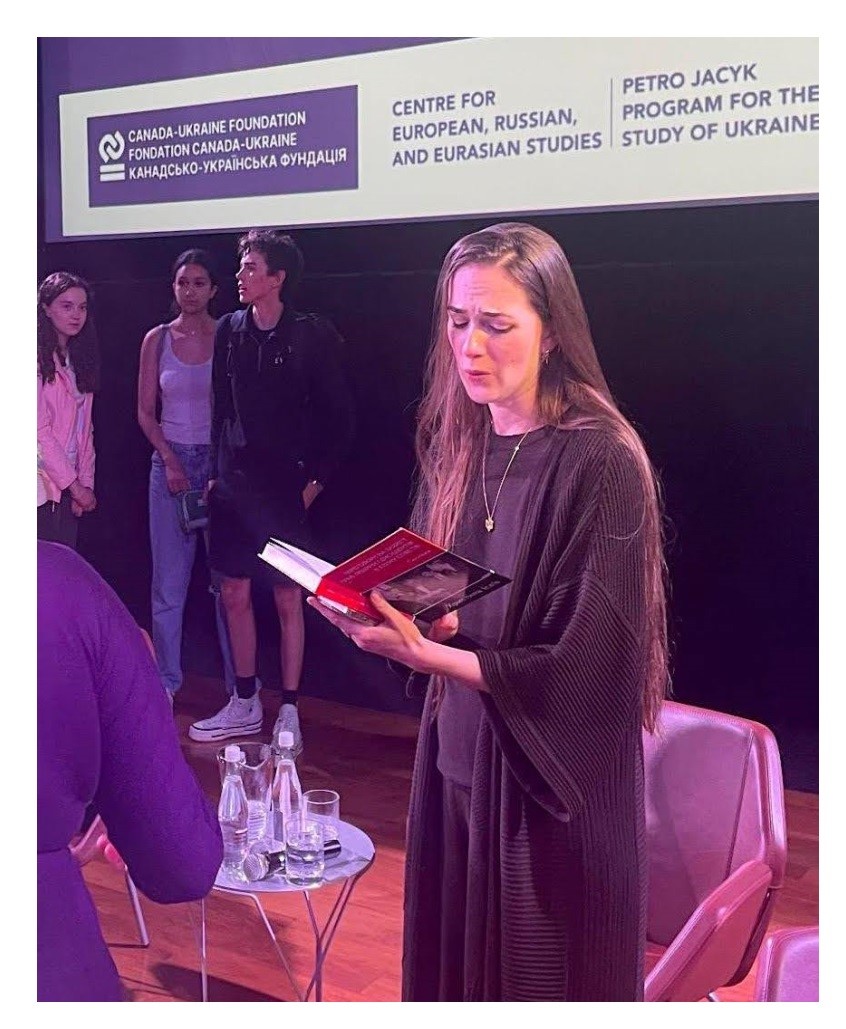

Photo: Oleksandra Matviichuk, head of the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize–winning Center for Civil Liberties in Kyiv, receiving a Ukrainian-language edition of Isajiw’s memoir at the University of Toronto, 7 June 2024. (Photo credit: O. Basmat.)

On the tenth anniversary of its publication, Negotiating Human Rights remains more relevant than ever as Ukraine defends itself from over two years of unprovoked Russian invasion, mass atrocities, and war crimes, and as the Kremlin once again imprisons Ukrainians and abducts Ukrainian children to Russia. During her Canadian tour, the Kyiv-based Ukrainian human rights lawyer and civil society leader Oleksandra Matviichuk—who heads the Center for Civil Liberties which received the 2022 Nobel Peace Prize for its human rights work in the OSCE region—was delighted to receive a Ukrainian-language edition of Isajiw’s book after her talk at the University of Toronto on 7 June 2024. And Ruslan Siromskyi, dean of the Faculty of History at the Ivan Franko National University in Lviv, invited Christina to present a series of five lectures in the fall to his students, covering the book’s topic and the importance of regional, national, and international NGOs in promoting Ukrainian human rights issues. Yet, in the realm of human rights and Ukrainian studies, few in the Western diaspora are aware of the history of the Helsinki Process or of the efforts it took to bring the first Soviet political prisoners to public awareness, let alone to get them released.

Sophia: What inspired you to write your book?

Christina: In 1973, the first Conference of Security and Cooperation in Europe (CSCE, today the OSCE) took place—in Helsinki—with the participation of 35 countries. I saw the conference as a great opportunity to lobby worldwide for the release of thousands of political prisoners, and in 1976 I became the coordinator of the Human Rights Commission (HRC) of the World Congress of Free Ukrainians. After the collapse of the Soviet Union, my job as a representative of the HRC transitioned to NGO status. Ukraine became a sovereign state, capable of defending the rights of its citizens—and we, the public sector of the Ukrainian diaspora, had to relinquish our fight of 20-plus years to the leadership of Ukraine.

At that time, I assessed the value of my archive and tried various ways to secure its legacy. I searched for other accounts that might have described our activities in the diaspora, but to my surprise there were very few newspaper articles and no books. I decided to write this book as documentation of our work and to highlight the importance of these documents for history. I also knew that published estimates of the number of political prisoners in the Gulag were then at over 465,000, so I decided to publish my account.

Sophia: What challenges did you face?

Christina: I faced many challenges in my work. The zeal of one individual requires the backing of likeminded supporters from the NGO community as well as allies in political and diplomatic circles. Nothing existed back then, and I needed to build support here in Canada, so I lobbied the federal government for the creation of a Standing Committee on Human Rights. I also needed financial backing from my community to be able to print leaflets, mail hundreds of news releases that I wrote documenting individual cases, and finance my trips to attend the international conferences of the CSCE in different member countries. I also asked for additional support from the Ukrainian Journalists’ Association of North America, which endorsed me and gave me press accreditation. This allowed me, as a reporter, to attend all the closed sessions to which only the press was admitted, giving me a much more immediate insight into these meetings among the representatives of 35 nations.

Sophia: What was your greatest reward in writing the book?

Christina: My archives are now proudly housed at the Ivan Franko National University in Lviv, Ukraine, and according to the dean of the Faculty of History, numerous students are writing their theses on the historical importance of human rights activism for Ukraine, as well as on the importance of regional and national non-government organizations, which strengthen the capacity of a state and enable it to resist existential threats to itself or its citizens. The reward to me is prevention of the loss of that precious material I had been working on for 25 years. I had tried several archives, but those places declined, so I wrote a book. To my way of thinking, this was profoundly, uniquely Ukrainian documentation that should not be lost in the attic of my home or scattered in the basement premises of the WCFU. For example, this collection includes the only White Paper the US State Department ever published on the Ukrainian Catholic Church—one I had researched for the WCFU.

Sophia: What are your insights gained from the process of writing your book?

Christina: As an American-Canadian dual citizen lobbying in both countries, I talk about the widely different approaches within North America. Also, as a Ukrainian, I wanted to shed light on the little-known plight of Ukrainian dissidents.

Sophia: It’s clear why historians would find specific value in your book, but why do you think we should all read it?

Christina: I tried to write it in a lively way, to include some anecdotes and numerous illustrations in order to evoke the atmosphere of these meetings and the interactions that took place in the process of carrying out human rights work and lobbying for our Ukrainian political dissidents. After all, I was an ordinary member of the diaspora community when I began this work, and it is a memoir of one person’s journey to do something to help push back against the human rights violations of innocent men and women—who didn’t deserve the treatment they received at the hands of an authoritarian government. Ukraine has always held a pivotal role in history. At every conference I stressed that Ukraine was a strategic element in all East-West relations during Soviet times, and it is a pivotal issue today that concerns Europe’s very survival.

My book provides actual documentation of the proceedings at the many international conferences I attended and describes the work of other groups with whom I cooperated. There were many revolutionary changes that occurred within the framework of the Helsinki Process and intergovernmental negotiations, and I documented these on the CD that comes with the book. So, while it is an important tool for historians, the book was written so that everyone could see for themselves virtually every document mentioned in the text—over 100 of them. If not exactly a “how-to” book, it’s a “how-it-was-done” of that historic time for anyone who is interested in continuing that work in today’s reality.

As one reviewer has written: “Negotiating Human Rights represents a must-read for scholars of the Helsinki network and a fascinating yet challenging read for a broader audience.”

Left Photo: Levko Lukianenko & Christina Isajiw in Brussels cafe 1989

Right Photo: Christina Isajiw on R with Danylo Shumuk, Nina Strokata-Karavanska, Osyp Zinkewych, James Mace, in DC

Photo: Christina Isajiw, press passes

Christine Isajiw’s memoir Negotiating Human Rights: In Defence of Dissidents during the Soviet Era is available for purchase on CIUS Press.