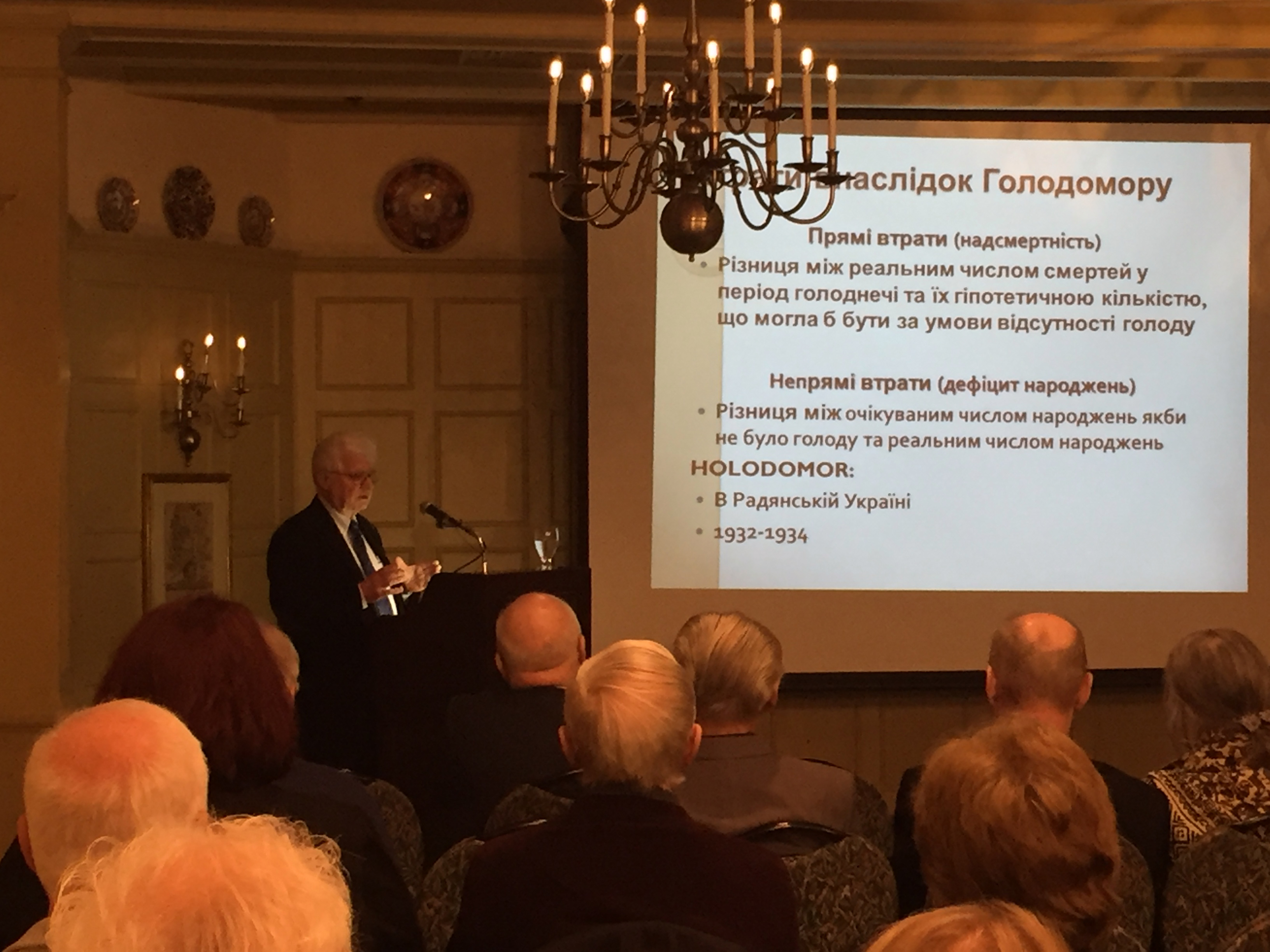

Dr. Oleh Wolowyna delivering a lecture in Toronto on February 22, 2018.

Demographer Oleh Wolowyna delivered a lecture in Toronto on February 22 titled "Regarding Questions about the Study of the Holodomor." The event was sponsored by the Holodomor Research and Education Consortium (Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta), the John Yaremko Chair of Ukrainian Studies at the University of Toronto, the Shevchenko Scientific Society of Canada, the Ukrainian Canadian Research and Documentation Centre, the Ucrainica Research Institute, and the BCU Foundation's Yurij Skripchinski Holodomor Education Fund.

In his presentation, delivered in Ukrainian, Professor Wolowyna discussed the issue of how many lives were lost in the Holodomor, the results of research conducted together with his research team, and the methodology used in determining mortality rates.

Wolowyna, who is Professor Emeritus at the University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill, has been systematically studying the question of the number of deaths during the Holodomor for the past five years together with researchers from the Institute of Demography and Social Sciences of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine: Omelian Rudnytsky, Nataliia Levchuk, Pavlo Shevchuk, Oleksandr Gladun, and Alla Kovbasiuk. The team has been deliberate in its approach while cautious and conservative in releasing findings, publishing results first in English in peer-reviewed journals before circulating more broadly.

Wolowyna began his presentation by defining terms. In establishing the number of victims, the demographers consider those deaths within the boundaries of the Ukrainian SSR that can be directly or indirectly attributed to the Holodomor during the Famine period of 1932-1934, as distinct from deaths that would have occurred had there been no famine. Dr. Wolowyna then spoke about the methods used by his group to arrive at a figure of 3.9 million losses. The vast majority of these deaths occurred during a huge spike in mortality that started in the early part of 1933.

Wolowyna and his colleagues were able to ascertain the number of deaths as percentages of the population at both the oblast (provincial) and raion (county) levels. The data shows that at the village level, the greatest Famine losses occurred in the Kyiv and Kharkiv oblasts of the day-the traditional Ukrainian steppe-forest heartland-rather than in the grain-growing steppe regions to the south as had been generally assumed. The raion mortality figures confirmed the concentration of deaths in the geographic centre of Ukraine but also show considerable variation in death rates even between adjacent counties.

The research group was also able to establish figures for famine losses throughout the Soviet Union: 8.73 million at the all-Union level, with losses of 3.92 million for Ukraine, 3.26 million for Russia, including the Kuban region, and 1.26 million for Kazakhstan. In terms of proportion of the population, Ukraine lost 12.9 percent of its inhabitants, while Russia lost 3.2 percent.

The demographers used Soviet-era census figures, vital statistics records, among other sources. Dr. Wolowyna explained that while some vital statistics reports had been destroyed in Ukraine during the Second World War, monthly reports were routinely forwarded to Moscow and were accessible to his team, even during its last research trip there taken in January 2014. Wolowyna also discussed the Soviet demographers who were either killed or imprisoned as a result of their work on the 1937 Soviet census, which was rejected because it showed figures that did not appeal to the regime.

Wolowyna noted that virtually all scholarly estimates of Holodomor victims are in the range of 2.6 to 5.0 million and examined arguments of those who promote the number of Holodomor victims as 7.0 million or more, most notably Volodymyr Serhiychuk of Kyiv National University. Wolowyna pointed to an article by S. Sosnovy from 1942 which was reprinted in the newspaper Ukrainski visti in Neu-Ulm, West Germany, in 1950. In the article, Sosnovy clearly cites a figure of 4.8 million (possibly 5.0) direct Famine deaths, but Serhiychuk adds other population losses noted by Sosnovy (up to 2.7 million) to reach a figure of more than 7.0 million. The figure of 7.0 million became regarded in the Ukrainian diaspora as authoritative.

Wolowyna addressed Serhiychuk's charge that documentary evidence in Moscow has somehow been falsified by noting that before the Holodomor the authorities had no motivation to falsify documents. Wolowyna also pointed out that Serhiychuk's methodology is faulty because it does not take into account migration from (and into) Ukraine.

In the Q&A session, Dr. Wolowyna fielded a question regarding whether the figures he presented, specifically regarding the higher mortality rates in the Ukrainian heartland, were proof of the Holodomor as genocide. He responded that while genocide is a legal concept and demographers are not qualified to make such determinations, the findings could potentially support a case for genocide. As well, the team's research can be used to make the case that the famine in the early 1930s was not experienced in equal weight throughout the Soviet Union.

In his response to another question, Wolowyna underlined the need for general consensus on a figure for Holodomor losses. He stated that if Ukrainians want broader recognition of the Holodomor as genocide, they need to reach some agreement on the number of losses. That said, Ukrainians face considerable political opposition on the genocide question, particularly from Russia. Wolowyna also noted that promoting inflated mortality figures damages credibility and risks harming rather than supporting calls for Holodomor recognition.

Contact: Marta Baziuk

Phone: 416-923-4732

Email: hrec@ualberta.ca

Author: Andrij Makuch