Fit for Royalty? An Investigation of an Embroidered Silk Robe

"Embroidered Silk Robe for the Dowager Empress," 1885-1908, blue silk satin embroidered with silk and metal-wrapped threads, Mactaggart Art Collection, University of Alberta Museums, Gift of Sandy and Cécile Mactaggart, 2005.5.250

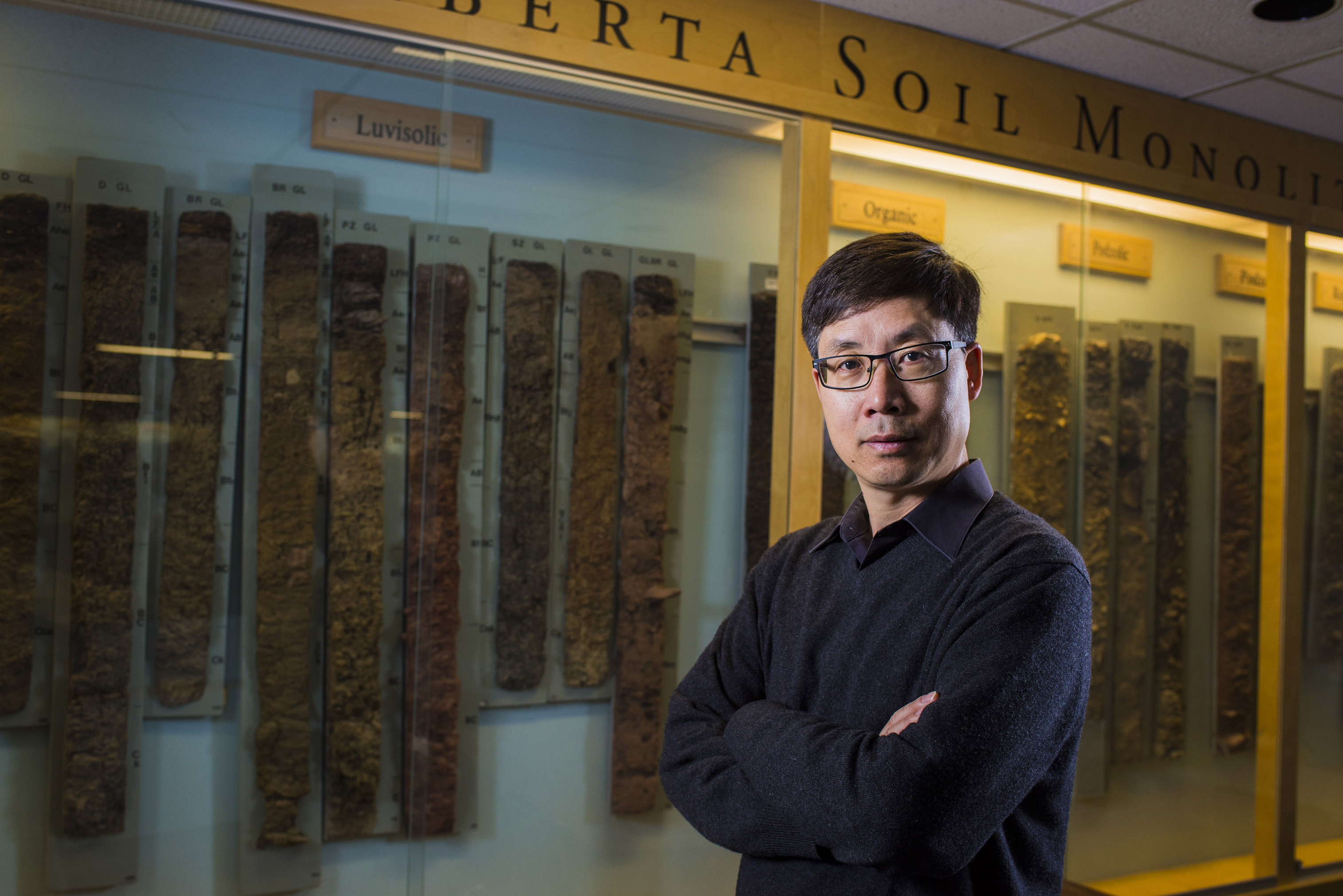

Seemingly innocuous, this embroidered semi-formal robe (chenyi) made for a woman, from the Mactaggart Art Collection carries layers of symbolism and meaning related to one of the most powerful women in the Qing Dynasty. In a time when imperial women lived in mostly secluded private apartments; Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908) remained a powerful political figure who forged relationships with western foreigners and kept meticulous control over her public image. She entered into the Qing Imperial Court in 1852 as a young concubine for Xianfeng Emperor and bore a son that became Tongzhi Emperor. Later, she defied rules of succession and installed her nephew as Guangxu Emperor. The empress dowager acted as co-regent for both her son and nephew, which gave her even more power before her death in 1908.

In the late Qing Dynasty, chenyi, or informal court robes, became popular among the imperial elite women as this garment was not regulated by official codes and could be styled in multiple colours, motifs, and shapes, as opposed to more formal robes.1 In comparison to another informal robe style, the changyi–often worn overtop the chenyi, this robe has narrower sleeves and no side slits. The sleeves follow the general shape of more formal Manchu style robes, which would typically extend longer and end in a horse-hoof shaped cuff, and the inclusion of phoenixes still follows the conventions of formal court attire.

This chenyi, which is similar to garments known to be worn by the empress dowager, features many material and symbolic clues as to its possible wearer. The blue background with a mauve border, made from aniline dyes introduced from Europe at the end of the 19th century, reflect the empress dowager's preference for “subdued” (by Chinese standards, especially when compared to the brilliant yellow and red formal robes of the imperial court) flattering cool tones that were appropriate for a widow to wear.

Eight mythical phoenixes, with a hidden ninth phoenix under the outer flap, cover the robe in a pattern similar to a dragon robe alluding to the “heavenly perfection” of the high-ranking wearer. Mythical phoenixes, or fenghuang, which are feminine in contrast to the masculine dragon, were reserved for women of the highest rank and they represent their power. Empress Dowager Cixi was often depicted with phoenixes, such as in this portrait famously painted by American Katharine A. Carl, in which she is surrounded by nine of the auspicious birds. Another symbol on the robe appears as two versions of the shou character, which symbolizes longevity.

Detail of "Embroidered Silk Robe for the Dowager Empress," 1885-1908, blue silk satin embroidered with silk and metal-wrapped threads, Mactaggart Art Collection, University of Alberta Museums, Gift of Sandy and Cécile Mactaggart, 2005.5.250

Boldly coloured peonies–in pink, mauve, blue, and white–fill the background of the main fabric. These flowers have been expertly rendered in a flat, even satin-stitch with an ombre effect, which adds dimension to every blossom. Peonies are the flower related to springtime and their inclusion on this robe may represent the feminine beauty of the wearer.2 Although we cannot officially confirm this robe was owned by Empress Dowager Cixi, she was known to have a fondness for peonies, and this style of robe certainly influenced the style of multiple other extant robes. Certainly, the pairing of peony, the king of flowers, with phoenixes, the most supreme bird, alludes to a high-rank wearer.

1 Wang, Daisy Yiyou and Jan Stuart, Empresses of China’s Forbidden City, 1644-1912, p. 212

2 Garrett, Valery, Chinese Clothing: An Illustrated Guide, p. 59