Peonies bloom in the imperial garden

Detail of "Peonies," 1905; Empress Dowager Cixi; Mactaggart Art Collection, University of Alberta Museums; Gift of Sandy and Cécile Mactaggart; 2004.19.4

From late spring to early summer, beautiful peonies bloom in Edmonton gardens and across the University of Alberta campus. In Chinese culture, peonies represent nobility, beauty, and good fortune—making them an important auspicious symbol and the subject of the hanging scroll Peonies (2004.19.4) from the Mactaggart Art Collection. As the king of flowers in China, the peony is much loved by all and was particularly popular with aristocrats and wealthy merchants during the Qing dynasty (1644-1911). For centuries, painters and artisans have been inspired by peonies due to their luxurious and enchanting nature.

This hanging scroll depicts two blooming peonies amongst twigs and leaves. It features a large, vivid-red flower in the centre and a light-pink flower on the top. Both flowers were painted with the Mogu (“boneless”) technique; a traditional Chinese painting technique using ink and colour washes without an outline. In contrast, the artist also used the Gongbi technique, a style that uses a detailed and realistic brush stroke, to depict twigs and leaves. The contrast between the detailed and precise Gongbi and the unfettered Mogu techniques adds depth to the composition and makes the flowers seem more vivid. The picture illustrates the tree peony, or mudan, a woody shrub native to China.

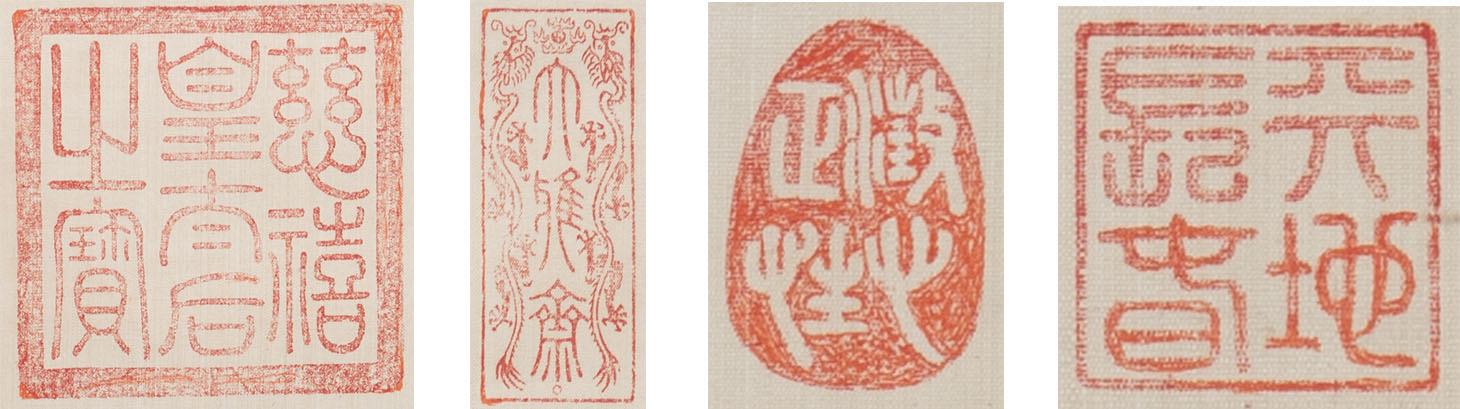

Traditional Chinese paintings always include inscriptions and seals that provide important information about the artist and the history of the painting. On the top right of this hanging scroll, seven large characters display the title of the painting (shan yuan hua kai fu kue chun), literally translated as the “blooming in the imperial garden reveals a prosperous and honourable spring.” On the lower right, the vertical row of calligraphy (guangxu yisi mengchun shang huan) demonstrates the painting’s date of creation—the first month of 1905. The calligraphy also includes two characters representing the imperial authority.

On this hanging scroll, there are four red seals. These include a large square seal at the top centre and three smaller seals along the right.

(1.2) Da ya zhai (“from Cixi’s painting studio”)

(1.3) cheng xin zheng xing (“honesty and positivity”)

(1.4) tian di chang chun (“the everlasting spring of heaven and earth”)

Clues to the artist’s identity are found among these seals and in the two Chinese characters, yu bi, which literally translated as “the authority’s pen.” Surprisingly, the authority mentioned here is not Emperor Guangxu (1871-1908) but Empress Dowager Cixi (1835-1908), both from the late Qing Dynasty. The name of Empress Dowager Cixi is in the inscription of the large seal (Figure 1.1), which says “the treasure of Empress Dowager Cixi.” Also, the other three seals possessed by Cixi represent the empress dowager herself.

During the late Qing court, Empress Dowager Cixi was the most important woman—even more powerful than the emperors. In addition to politics, she was interested in painting and calligraphy. The empress dowager often bestowed her paintings on subordinates or foreign ambassadors as gifts. As she was too busy to create her own paintings, she commissioned private painters as her “ghost painters”1 to make these paintings in her name. Despite this, many paintings under her name exist in collections owing to her generous gifts.

1 Among the ghost painters to Empress Dowager Cixi, Miao Jiahui (1841-1918) was an outstanding female painter who served as a tutor for Empress Dowager Cixi in Beijing. (Sullivan, Modern Chinese Artists, 117.)