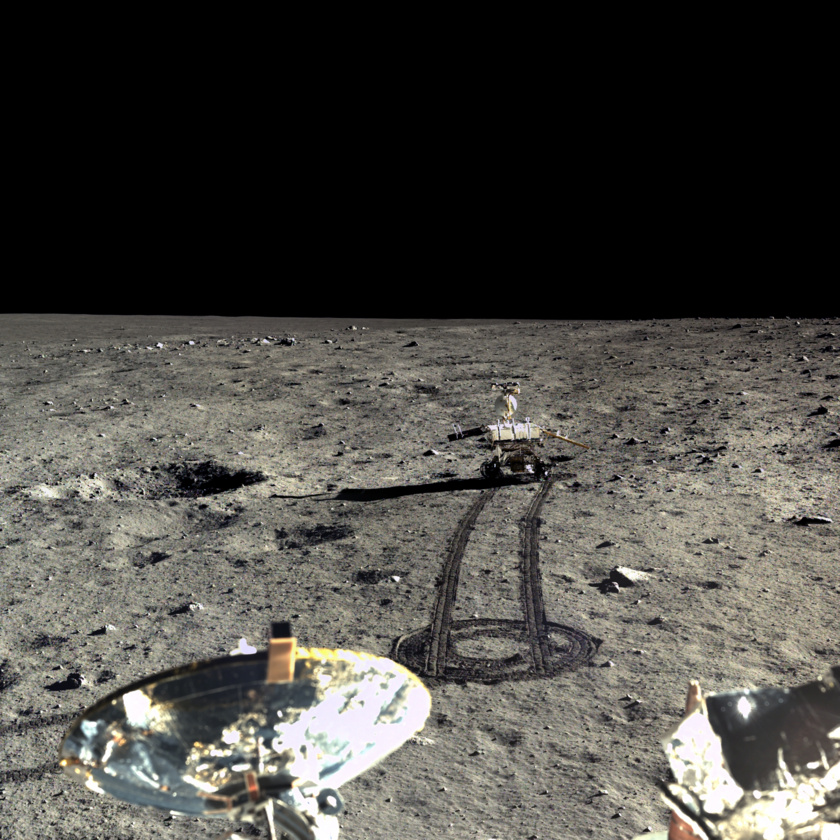

JADE RABBIT ON THE MOVE

Image credit: Chinese Academy of Sciences / China National Space Administration / The Science and Application Center for Moon and Deepspace Exploration / Emily Lakdawalla / Planetary Society

The pace of missions to the Moon is set to surge by 2020. Several space agencies and firms are preparing lunar missions. China is near the forefront of this coming renaissance in lunar exploration. Many of the missions proposed by different actors target the same few small spots of interest on the lunar surface. These developments highlight the need for consultation among established and new spacefaring actors about the governance of activities at crowded lunar sites.

The Moon is about to become a much busier place

At the height of the Cold-War Moon race, the superpowers together launched a combined ten or more lunar missions a year. That rate of lunar activity plummeted with the end of the Apollo program in 1972. After that, the U.S., Soviet/Russian, and, since 1990, Japanese space agencies continued to send robotic missions to the Moon's orbit and surface, but far less frequently. Years went by without lunar visits. In the 2000s, lunar activity picked up again as Europe, China, and India launched their first missions.

Today, we are on the cusp of another burst of lunar activity. A wave of new players is pursuing exploration projects. Over ten different agencies and firms worldwide are preparing to launch a total of 20 or more missions to the Moon before 2020. A dozen more missions scheduled for 2020 and beyond, some of which are already funded, could follow. At least two missions will carry humans, including private U.S. firm SpaceX's flight of two passengers planned for late 2018.

Many of these upcoming missions are going to the same few places. That is because, although the Moon's surface is vast, its most interesting parts are small. For now, the greatest potential for scientific discovery and resource utilization lies in a handful of sites. Among these are the Peaks of Eternal Light at the poles - areas each no larger than a football field. These thin ridges and rims and small patches enjoy extended periods of sunlight, making them ideal locations for science, settlement, and a vast range of other activities that require solar power. Several national agencies plan to visit the vicinity of the Peaks in the coming decade, including China's.

The various polar missions present potential complementarities, but crowding at these sites could also complicate lunar activities. For example, radio astronomy and other communications equipment items around the Peaks could interfere with each other. Solar panels erected there could cast shadows that limit others' access to this critical energy source. Rovers and other vehicles could kick up lunar dust that disrupts all these installations. As the challenges of co-location grow, so will the need for governance mechanisms to address them.

China is at the forefront of this lunar renaissance

Among the various actors now aiming for the moon, China is a leader. The Chinese national lunar program is today the world's most active. The country's last two missions to the Moon marked a midway point in the ambitious China Lunar Exploration Program (CLEP). The program is designed to unfold over three phases, consisting of robotic voyages to orbit, rove on, and return a sample from the Moon.

In the first stage, the Chang'e 1 and 2 orbiters mapped the lunar surface, producing what affiliated scientists deem "the best global image of the Moon so far in terms of space coverage, image quality, and positioning precision." A second-mission orbiter also traveled to the Sun-Earth L2 libration point, a special region thought of as a parking spot in space, and flew by the asteroid Toutatis.

In the second stage, the Yutu (Jade Rabbit) rover touched down on the lunar surface. Yutu survived an immobilizing technical failure to operate for a record-breaking two and a half years, discovered a new type of lunar rock, and generated stunning new images. The Chang'e 5 mission, scheduled to launch in late 2017, will collect and return a lunar sample.

In the third stage, another rover will return a sample from the far side. Planned for 2018, Chang'e 4 will mark a first - not only for China, but also for the world: humankind's soft landing of a vehicle on the far side of our natural satellite. The spacecraft will deploy a rover to conduct topographic and geological surveys, sending its findings home through a relay satellite. Succeeding it in 2020, Chang'e 6 will collect a far-side sample and return it to Earth. The stage 3 missions will also perform geological studies and low-frequency radio astronomy research on the far side, yielding insights into the Moon's formation and evolution. Officials indicate that, at some point after 2020, China will send humans to the Moon.

Through these missions, CLEP is developing the core capabilities required to support a vast range of operations in cislunar space, complementing elements of China's larger space infrastructure. These capabilities already include autonomous guidance, navigation, and control of spacecraft, long-range communications, and complex landing systems. CLEP has also developed an advanced tracking, telemetry, and control system and a communications network to support these operations. The program has demonstrated a spacecraft's direct Earth-Moon orbital transfer (twice) and performed an asteroid rendezvous.

Yutu captured by the Chang'e 3 lander in late 2013. Image: Chinese Academy of Sciences / China National Space Administration / The Science and Application Center for Moon and Deepspace Exploration / Emily Lakdawalla / Planetary Society

China is poised to play a leading role in multinational lunar projects

Looking toward Chang'e 6 and beyond, Chinese scientists and engineers envision a framework for international cooperation on major lunar projects. Their proposals join a budding international conversation about seizing the benefits of and managing the challenges presented by the coming renaissance in lunar exploration.

In the vision presented by CLEP's architects, a first stage of international lunar cooperation focuses on exploring the poles, soon to become hotbeds of activity. CLEP engineers propose joint, multinational work toward prospecting of the Moon for resources, scientific research, and applications. In a later stage, they advocate establishing a lunar station suited to long-term research and large-scale utilization. This imagined facility shares features of the European Space Agency's proposed Moon Village and the base envisioned by some U.S. advocates.

To build these structures, CLEP leaders propose a cooperation model in which governments coordinate their activities, partner agencies independently develop complementary spacecraft, and industrial actors share resources and technology. This approach draws upon a now significant record of international participation in Chinese missions. China's space programs have already enabled organizations from both developed and developing countries to participate in space-based research.

China's leaders hope their country will play a leading role in future multinational lunar projects. The country's substantial programs create opportunities for international participants to join in supporting roles. For example, in the world's first commercial lunar mission, launched in 2014, a European instrument flew on a Chinese platform. Over ten space agencies and institutions have proposed payloads to fly on the coming Chang'e 4 mission.

CLEP's development plans - for both the hardware of space vehicles and the software of international cooperation - serve long-term strategic ambitions. Chinese space experts have for decades stressed the need to establish the country's status as an actor that has a say in the development and utilization of strategic domains. Maintaining a regular physical presence and leading international projects ensures that China is included in future processes shaping the governance of activities on the Moon. In short, for China's leaders, it is a way of guaranteeing, among other advantages, 'a place for one's mat (一席之地)' in an important arena.

Now is the time to devise new mechanisms for coordinating activity on the Moon.

As the world's established space agencies, including NASA, ESA, and JAXA, plan their future activities on the Moon, they will have no choice but to shape these around an ambitious and steadfast Chinese program with a growing lunar footprint. The question before many governments seems to be, then, what degree of coordination, cooperation, and technology sharing in lunar activities is appropriate toward China. Existing fora, such as the International Space Exploration Coordinating Group, also provide settings for deliberation and consultation on these matters.

While the question of how and how much to engage with China in space remains fundamental, more practical and immediate issues are likely to demand space policy experts' attention in the short term. Possible interference between installations and competing claims over the most valuable parts of the lunar surface may soon arise. Some of these problems can be managed piecemeal, as they occur, but others are best addressed within an institutionalized, systematic framework. To meet these challenges, spacefaring states must develop a vision for how diverse parties' activities on the Moon can and should be governed. Without this deliberation and effort at institutional innovation, Canada and its traditional partners may end up accepting de facto arrangements imposed from without.

Alanna Krolikowski is a postdoctoral researcher in the China Institute at the University of Alberta.