The retreat of the Republic of China (ROC) government and its armed forces to Taiwan did not occur in a strategic vacuum. The somewhat suppressed struggle between the Kuomintang and the Communist Party of China (CPC) between 1937 and 1945 was subsumed in the global conflict of World War II. Similarly, the renewed high-intensity civil war between the ROC and the People's Liberation Army (PLA) played out in an international environment dominated by the deteriorating relationship between the Soviet Union and the United States.

However, with the decisive defeat of ROC forces on the Chinese mainland in 1949, and the subsequent retreat of both Chiang Kai-Shek and his government to Taiwan, the attitude of the United States shifted. With the successful PLA invasion of Hainan Island in April 1950, and with a concentration by the PLA on the Chinese coast for the planned invasion of Taiwan, the US Government appeared unlikely to commit further financial or political support to the Chiang regime.

"It is possible, as in 1950, that a breakdown in the US-China relationship might underline the strategic advantages of Taiwan to Washington, but this prospect is uncertain at best. The economic rupture of East Asia caused by a meltdown of deeply intertwined relations between the US and China would not spare Taiwan, or its economy."

In a development that would certainly have caught the eye of both Beijing and Moscow, US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles disclosed in a memo to the Pentagon, and later publically reiterated, that the security perimeter of the US would be drawn to the east of Taiwan, not to the west of the island. This was a clear indication that US forces would not be committed to the defence of Taiwan or the ROC.

However, when forces from the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK) crossed the demarcation line determined by US and Soviet forces in 1945 - apparently, we now understand, with the approval of Stalin - the security environment of East Asia was radically and permanently altered, with profound implications for Taiwan. US forces were forced back to a small perimeter around Pusan, Korea, but a major US and broader Western military coalition was formed that would see the first direct combat between US and PRC armed forces. That conflict resulted in a delay of strategic rapprochement between Washington and Beijing that lasted for almost two decades, until the 1969 surprise contact between the US and the PRC, led by Chairman Mao and President Nixon. Without the outbreak of the Korean War, it is probable that the PLA would have completed the military conquest of Taiwan, and that the relations between Washington and Beijing might not have become as antagonistic as they did in the 1950s and '60s. This latter prospect is, perhaps, less likely given the still intact relationship between Beijing and Moscow in the early 1950s, and the corrosive debate in Washington regarding the Soviet Union and its military challenge to the West.

Since the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, but especially since the beginning of the PRC's "open door" policy in 1978, the quest for economic growth and prosperity has dominated East Asia. Since 1969, the complex but generally stable relationship between Washington and Beijing safeguarded Taiwan's de facto security, but it also put off Taipei's political goal of de jure international sovereignty.

Fast forward to 2017: the miracle of East Asian post-WWII recovery (especially applicable to Japan), and the export-led fluorescence of East Asia that brought general prosperity to Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and, post-1978, to the Chinese mainland, proceeded largely without interstate conflict in East Asia. Tensions were largely subsumed under a pragmatic US-PRC relationship that became focused primarily on trade. While it is true that unresolved disputes regarding rival claims in the South China Sea remain political flashpoints, and divergent US and Chinese interpretations of Chinese actions in this region remind us that strategic calculations were never entirely absent from East Asia, territorial disputes have not distracted from East Asia's broad focus on economic growth.

However, the unresolved issues exposed during the Korean War have persisted, and these issues have been exacerbated with the gradual progress of the DPRK in building nuclear weapons as well as the capacity to deliver such weapons by missile. But despite periodic tensions revolving around incidents, such as the seizure of the US naval vessel Pueblo, or incidents in or around the De-militarized Zone (DMZ) between the DPRK and the Republic of Korea (ROK), on-again, off-again contacts involving the Six-Party Talks (US, PRC, Russia, Japan and the two Koreas) gave hope to the international community that the Korean security issues could be managed, if not resolved. Likewise, the deep economic trade and investment relationship between the PRC and Taiwan gave the impression that Taiwan's search for its own path could, perhaps, be compatible with a pragmatic 21st-century PRC world view. Relative stability and pragmatism had become the hallmarks of East Asian relations, despite significant military flashpoints.

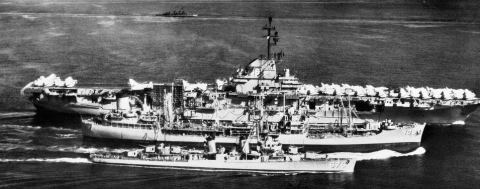

USS Lexington (CVA-16) and the destroyer USS Marshall (DD-676) in the eastern Philippine Sea during the 1958 Taiwan Strait Crisis. Image credit: CC by Wikipedia Commons.

But 2017 has challenged assumptions that East Asia is simply a region focused on trade and economic growth: US President Trump, both in his presidential campaign and in his early presidency, has shown a willingness to challenge the status quo in terms of US economic, political, and security relations with East Asia, including the crucial US relationship with China - the linchpin of East Asia security.

Of special significance in 2017 is the rapid emergence of fast-moving North Korean nuclear weapons development. Decades of US Korean policy aimed at preventing the emergence of North Korean nuclear weapons have failed, and East Asia now faces the possibility of a high-intensity war on the Korean peninsula that would have instant and potentially catastrophic consequences for the region, including the unraveling of trade and supply chains that bind East Asia to the global economy. Taiwan would not be immune from these developments. As previously noted, Taiwan was preserved from absorption into the PRC in part by the outbreak of the Korean War. But it is not clear whether a deteriorating East Asian security regime would provide the same result. The outbreak of "Korean War II" would send the insurance rates for Taiwan's maritime links soaring, for both intra-East Asia and to out-of-region trade partners.

US military action against the DPRK carries substantive risks of a PRC military intervention in North Korea, and the concomitant danger of a breakdown in the US-China relationship. A recognition by Beijing of the importance of a sound relationship with Washington has served as a brake on any precipitous action against Taiwan, but fractured US-China relations or the possibility of renewed warfare on the Korean Peninsula would also risk a loosening of the PRC's restraint regarding its longstanding commitment to the integration of Taiwan into the PRC, at a time when Beijing is gradually acquiring the capacity to apply increased military and political pressure on Taipei.

It is possible, as in 1950, that a breakdown in the US-China relationship might underline the strategic advantages of Taiwan to Washington, but this prospect is uncertain at best. The economic rupture of East Asia caused by a meltdown of deeply intertwined relations between the US and China would not spare Taiwan, or its economy. The potential gains of closer political and military linkages between Washington and Taipei in the wake of fractured US-PRC relations would most probably be more than outweighed by the economic dislocation that would likely follow, as well as the prospect of a more aggressive stance by Beijing towards Taipei.