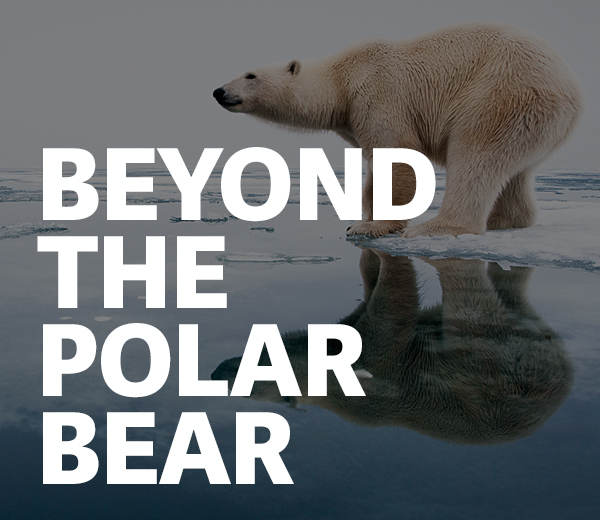

Photo by Pauls Souders / Worldfoto

Ian Stirling and Andrew Derocher are two of the world's foremost polar bear researchers. Together they pioneered research on the possible effects a warming world could have on the species. But they certainly couldn't have predicted the degree to which climate change would dominate their work over the long term. Listening to these experts as they bounce opinions, memories and ideas off one another offers a rare opportunity. The conversation is eye-opening as they discuss the state of polar bears, research and how climate change forced itself into their field.

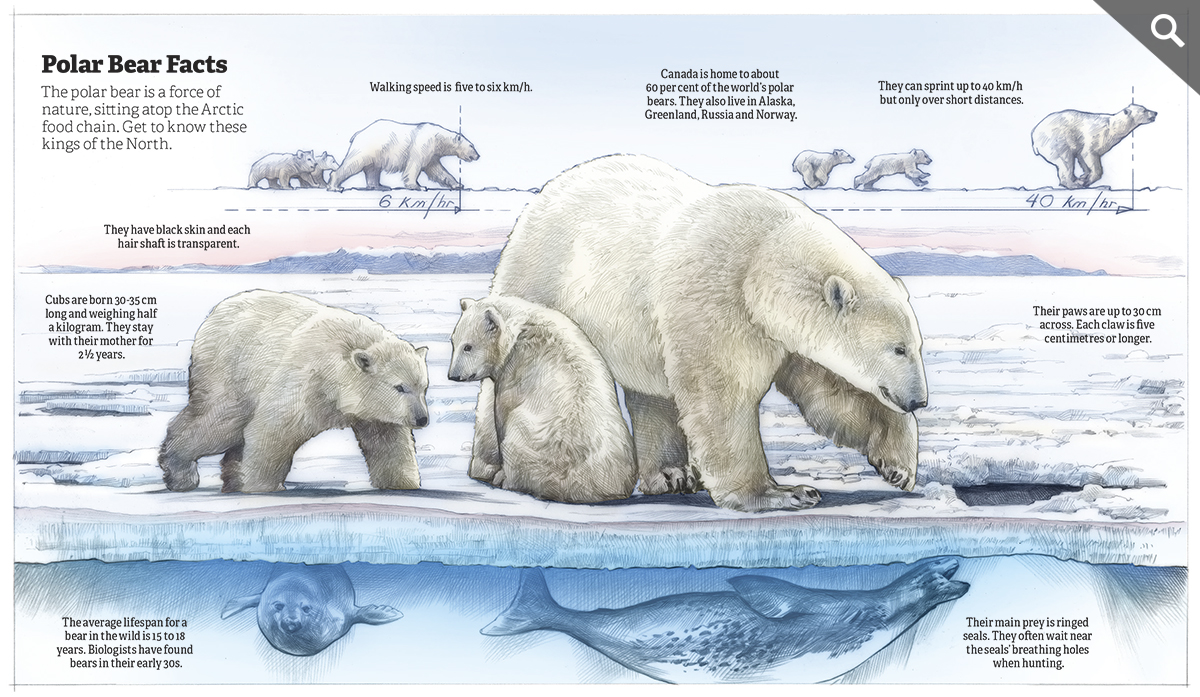

Illustrations by Bruce Morser

Ian Stirling

Adjunct professor in the Department of Biological Sciences

Andrew Derocher, '87 MSc, '91 PhD

Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences

Between the two of them, Ian Stirling and Andrew Derocher have more than 70 years of experience studying the Ursus maritimus (sea bear).

Sarah Pratt: When I talk to researchers about climate change, they repeatedly use the term "canary in the coal mine." Is that how you see polar bears: as a species that is an early indicator of changes in our climate?

Andrew Derocher: Yes, that's exactly what's happening. They are big, furry, meat-eating canaries. [laughs] I always say it's a simple story. It all comes down to the No. 1 concern globally: habitat loss. We lose the sea ice, we lose the bears. This is not an issue about polar bears; really, it's a global issue.

We could see the likelihood of climate warming coming early on, so we wrote a paper in 1993 about possible effects of warming on polar bears. Those predictions were borne out. Subsequently, we reviewed the topic in more detail in 2004 and again in 2012. You know, when Ian and I wrote our 1993 paper, we thought climate change was still far away on the horizon. I am absolutely stunned by how quickly the changes have come.

Ian Stirling: Leading up to the 1993 paper, I was originally interested in natural fluctuations in ecosystems. It didn't have anything to do with climate change. One day after looking at our long-term population-monitoring data from my project in western Hudson Bay, I said to Andy, "You know, there are some longer-term things going on underneath what we're seeing up front." I had set out to look at some completely legitimate but totally different questions, and climate change forced its way onto the agenda. We had to figure out what on earth was going on here; it was something besides what we were looking for. Andy left to study polar bears in Svalbard [Arctic Norway], and in 1999, with Nick Lunn, my colleague on the population ecology of polar bears in western Hudson Bay, I published the first paper that statistically confirmed the negative effects of climate warming on polar bears in the area.

"We can't move a northern species farther north." -Andrew Derocher

AD: Climate change has become a driving force in our continuing research, but not all of it. For example, I do work on toxicology and exposure to disease, while a lot of Ian's work has focused on relationships between polar bears, seals and sea ice. In other words, we had ongoing research interests long before climate change forced itself onto our agendas. I'd be happy if I die and was wrong about polar bears and climate change. [Gestures as though imagining the headlines.] "He was wrong and he died happy."

IS: Sadly, the predictions we made in the 1993 paper came true. I'm not happy about being right.

AD: Then the 2004 review paper really kick-started another process. It was instrumental for conservation groups who told us they were waiting for something they could move on for polar bears so they could push for endangered species listing in the United States.

IS: I had used my position as a research scientist with Environment Canada and an adjunct professor with the U of A to maintain the long-term population studies. I was able to keep the database going for several decades and train a number of graduate students. When everyone's efforts were pooled, we had a long-term database. A critical point is if you took pretty much any 10 years of our [polar bear] database or those on sea ice, there wouldn't be enough data to detect a statistically significant trend. But if you took 20 or 30 years, like we have in some places now, the trends become clear.

I think that's an aspect that's not well understood. It's fair to say that if the combined support from the U of A and Environment Canada hadn't made the long-term study possible, I think we would only now be finding statistically reliable stuff.

SP: That makes sense. Observation and data collection are vital. How about mitigation and adaptation? How do these relate to polar bears?

AD: This is not a species that is going to adapt to climate change. At the end of the last glaciation, they used to be as far south as Denmark and they're no longer there. They didn't adapt - they disappeared and moved farther north. The peril now is we can't move a northern species farther north. There are some big changes coming and the question is when.

You know, people say, "You're an advocate for polar bears," and I always come back and say, "I'm actually an advocate for the science of how polar bears are affected by climate change." It's clear in the Arctic because changes are amplified in the North.

Changes will happen in Edmonton, too. We might not have trees here in 100 years.

SP: Most of the province will likely be grasslands, according to U of A research that predicts a warmer, drier province.

AD: Yeah, it will all be grasslands, and different ecosystems will come here. It's the same thing in the North. We will have a new top predator, the killer whale. It has been shown their range is expanding in the North, especially Hudson Bay.

IS: And as ice decreases, killer whales will also prey on narwhals and belugas.

AD: I don't really enjoy talking about climate change; there's nothing fun about it. It has been extremely frustrating. If you read the literature about sea ice and climate, it's really hard to remain ignorant. You have to really work to be ignorant on this topic.

IS: I would add that we are outrageously attacked on a regular basis by climate deniers. I think what the deniers don't like about the polar bear studies is that the relationships are so clear: polar bears need ice to hunt seals.

SP: Do you feel a heightened sense of responsibility to the public when it comes to polar bears and climate change? After all, you are the faces of this issue.

AD: Often I come back to the issue of intergenerational unfairness. The current generation really doesn't have the right to leave the mess to future generations that we're currently leaving.

IS: I feel very strongly as a scientist that we need to make research available to the public in an accessible manner so they can make their own decisions based on real information. I think both of us feel a pretty strong moral obligation to do that.

I have grandchildren now and I believe very much in intergenerational unfairness - and that's just my own family, not to mention people in other countries.

Even in the United States, Florida is so low-lying, the cost of sea rise change there is huge.

SP: And you have a front-row view of the situation. When I see photos of you with polar bear cubs, it's amazing. What's it like to hold one, to be near them?

AD: It's a mix of emotions. They are incredibly beautiful, feel incredibly fragile, but you're also looking at incredible potential. This cub could grow into a huge bear that could walk to Russia, getting bigger and bigger along the way. The scary thing is to look into the future. In the Beaufort Sea area, the changes there are catastrophic. Many cubs in western Hudson Bay are starving.

IS: There are almost no yearlings in the western Hudson Bay populations. It doesn't take a rocket scientist to figure out the new cubs are not surviving well.

SP: Are you able to put on your scientist hat and see this happening and not feel … well, if it was me, I'd be so sad.

IS: I can't look at starving animals and think, "Oh that's life." You always have some unhealthy bears in any population, they all die sometime, but in places like western Hudson Bay we are seeing much higher proportions of skinny ones.

SP: So what can we do? Could we feed the bears?

AD: Actually, we proposed that in a recent paper. Trying to feed polar bears is interesting.

IS: And hugely expensive.

AD: But the problems people will face are more of an issue, with rising sea levels and so on.

IS: Eventually, the biggest wake-up call will be catastrophic. I think we're going to see world wars over water. We are totally unprepared, nationally, for climate change.

AD: I'm fairly optimistic we can change, I just don't think we're going to change quickly enough to save polar bears.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.