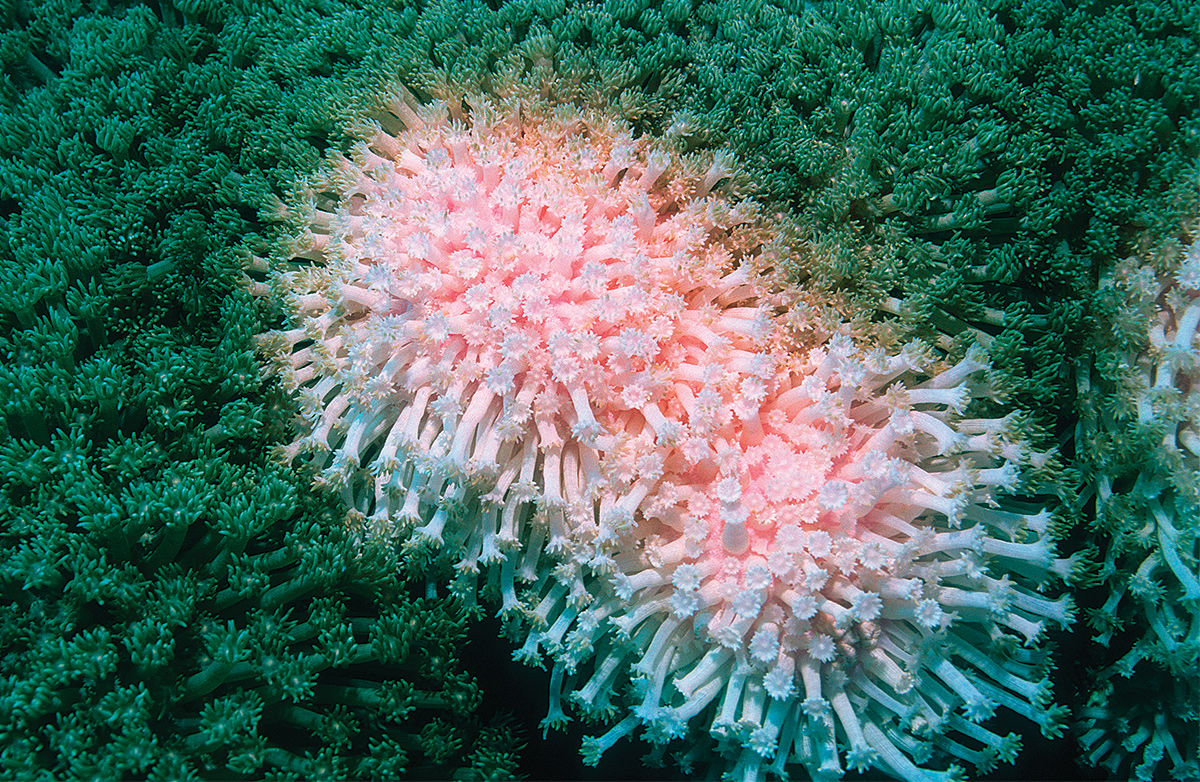

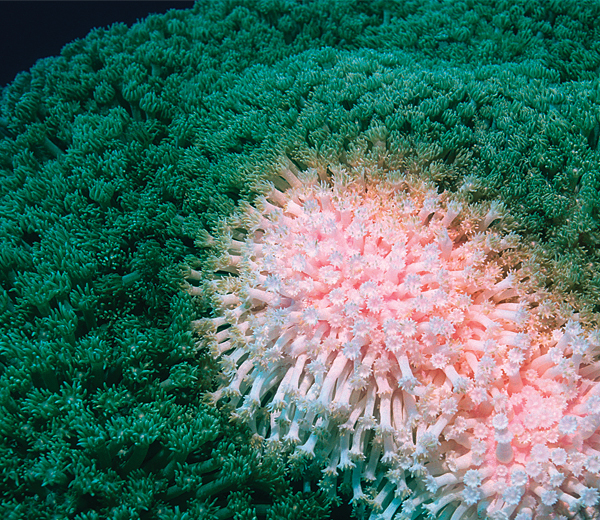

Photo by Georgette Douwma / NPL / Minden Pictures

When marine biologist Drew Harvell, '78 BSc(Hons), '81 MSc, recalls weaving her way through a bustling Indonesian fish market, it's the diversity that resonates with her. Even with nearly 30 years of experience as a professor and research scientist, Harvell marvels at the selection of fish and invertebrates: snapper, tuna, mackerel, octopus, shrimp - even stingray.

"It's mind-blowing to see all the food people get from the ocean, especially from coral reef habitats," says Harvell, who studies outbreaks of infectious disease in marine organisms.

You can draw a direct line from coral reefs, with their rich habitat, to the economic well-being of the fisheries industry. Coral reefs provide food, fishing jobs and tourism-related employment. There are about 30 million people worldwide who are almost totally dependent on coral reefs - either for their livelihoods or for the land they live on - and about 500 million people with some level of dependence, according to a National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration report for the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Beyond the bottom line, coral reefs provide erosion protection for coastlines, a sense of cultural identity and a potential for medicines that could tackle everything from cancer and HIV to arthritis and heart disease.

But climate change is threatening the health of the world's 284,300 square kilometres of coral reefs.

"I can say very definitively that climate change is basically driving whole ecosystems to endangerment." -Drew Harvell

"I can say very definitively that climate change is basically driving whole ecosystems to endangerment," says Harvell, who is a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at Cornell University in Ithaca, N.Y. "It's happening all around the world: Mexico, East Africa, Australia, Indonesia, and even the Florida Keys, where corals are on the northern edge of their temperature limits."

Warmer water temperatures stress the coral, which causes its resident symbiotic algae to leave. These single-cell algae that normally live in healthy coral are the source of the coral's food and its signature colour. As the algae depart, so do the bright hues of the coral, which begin to turn white in a process called bleaching. A bleached coral won't necessarily die - though some do melt away - but the stress caused by the rising water temperature can lead to outbreaks of disease among the coral.

An increase in CO2 levels in the air is also putting stress on the marine environment. Oceans absorb about one-third of human-made carbon dioxide, totalling 20 million tonnes per day. As more CO2 is released into the atmosphere, the chemistry of the oceans changes, lowering the pH and making the water more acidic.

Over recent decades, as oceans warm and become more acidic, outbreaks of disease in coral have increased in severity and frequency, according to a 2014 study, "Climate Change Influences on Marine Infectious Disease," to which Harvell contributed. The ocean has become 30 per cent more acidic over the past century and the rate of acidification is accelerating. All of this adds up to conditions not seen in the past 300 million years, according to the 2014 study, and the effects go far beyond the creatures living underwater. "Oceans and people are inextricably linked, and marine diseases can both directly and indirectly affect human health, livelihoods and well-being," the study's authors wrote.

As far north as the Baltic Sea and Alaska, people have reported outbreaks of Vibrio bacterial infections. The bacteria are present in marine environments and can cause infectious diarrhea, wound infections and sepsis from eating raw or undercooked shellfish or from exposure to contaminated seawater.

The good news: there still appears to be time to reverse this course by halting human-induced climate change while restoring reefs. Using sea grass is one way researchers are looking to help - sea grass beds can be filtration systems and restorative agents for reefs, says Harvell.

"It's a huge process to bring back a reef, but there are restoration efforts going on," she says. "Let's see if we can stop recording things dying and find ways to bring them back. We have to learn from the science to help us manage or avert what we are seeing."

Photo by Kevin Schafer / Minden Pictures

Is Climate Change Turning Sea Stars Into Zombies?

The largest example of marine disease outbreak in wild species is turning sea stars into the walking dead.

A wasting disease has attacked at least 20 species of sea stars along the Pacific coast. The infected creatures first show lesions, then their tissues decay, leaving their bodies to fragment and melt into piles of white goo. This grim death led the media to dub infected sea stars "zombie starfish."

The die-off is so drastic that sunflower stars have nearly disappeared all the way to Alaska, says Drew Harvell. In 2014, 70 to 90 per cent of the intertidal sea stars died at her research sites along the West Coast, including Bamfield, B.C., and Washington State's San Juan islands.

"This die-off is unprecedented in the 40-plus years that Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre has been in operation," says director Brad Anholt, '79 BSc(Hons). Though there is evidence that the outbreak is related to water temperature, it's still too early to say for sure whether climate change is the culprit, he says.

Harvell doesn't know if the sea stars will rebound. She continues to monitor populations while researching the immune systems of sea stars, working to understand how they naturally fight infection. "It's a means of doing something," she says. "They are a big concern and right now we just don't know what's going to happen to them."

Where Research Warms Up

At the edge of the Pacific on the west side of Vancouver Island, Bamfield Marine Sciences Centre is home to a University of Alberta branch campus. Researchers like Drew Harvell value the centre for its long-term data, which help demonstrate the effects of climate change. The branch campus and facility are also at the locus of warming coastal waters.

"Bamfield, along with the entire West Coast, has been humoured by phenomenally warming water," Harvell says. "I read in the New York Times a phrase - they called it the 'cauldron-like waters of the Pacific.' "

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.