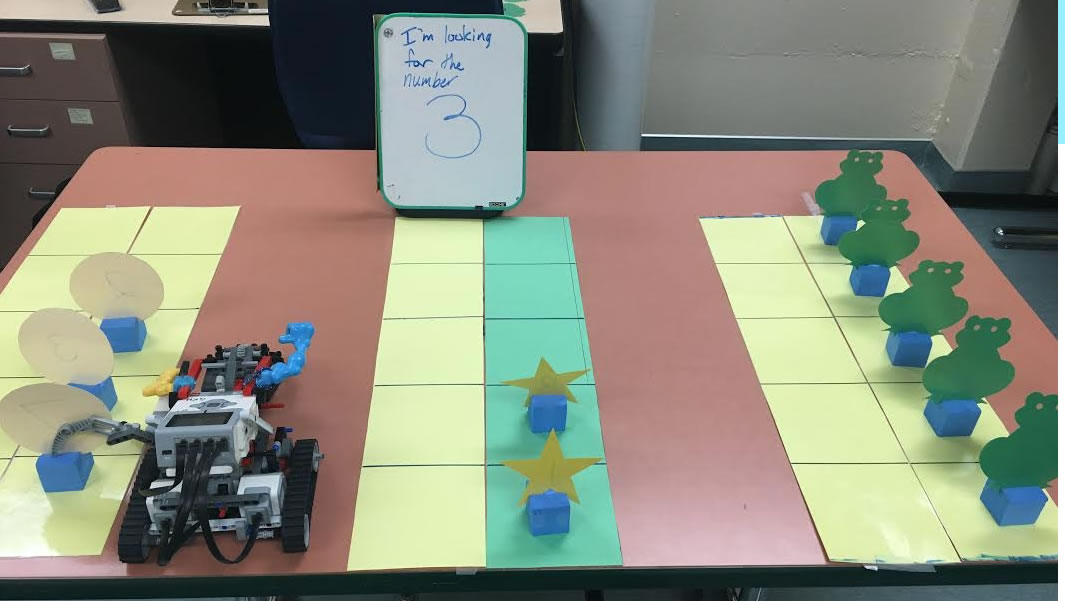

Student uses a robot for the hands-on part of learning math concepts.

Some of the most important developmental achievements happen within a child's school environment when they participate in hands-on activities that further their knowledge.

Early learning strategies teach students to add, subtract, divide and multiply by physically moving around objects to help them better understand the concepts.

But what if they couldn't do that?

A new University of Alberta, Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine study is looking at the role of assistive technology when it comes to children with disabilities in the classroom who are currently learning about mathematics.

"Many lessons teaching early learning concepts involve students manipulating physical objects in order to build an understanding of the concepts," explains Kim Adams, associate professor and director of Assistive Technology Labs, Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine, who is lead on the study. "For instance, to learn counting, children will sequentially touch objects and count aloud, or to learn subtraction they will physically remove items from a group and then recount them."

Essentially, students with little or no physical function in their upper limbs may have a hard time with the immersive portions of math subjects.

But assistive technology is looking to change that by acting as students' 'hands'.

Mini robots, or in this case, LEGO™ Mindstorms robots, allow students the ability to push, pull, point and carry objects on their own through the use of Bluetooth-compatible software.

"Children can control the robots in different ways. They can use single switches positioned next to body parts that they can control easily or they can use a head mouse and an interface on the computer screen," says Adams. "Some children have even controlled the robots through their communication device."

In all of these cases, commands are sent to the robot to perform movements like moving forward, backward, left, right, and opening and closing a gripper. In the case of counting, the robot moves along and points to objects as the communication device says the number aloud.

The hands-on approach enables students to create their own knowledge pathways, gaining more confidence in their ability to participate.

"When students first started manipulating the objects themselves in the lessons, we identified gaps in their learning," says Adams. "It seems when students have watched someone else do the manipulation in the past they weren't truly understanding the concepts. Doing the manipulation themselves with the robot helps make things more concrete for them."

Adams, along with her graduate student Paola Esquivel, are currently finishing up three in-depth case studies with students in preschool, grade one and high school. From this, they were able to examine students' experience using the robot compared to using the computer, and compile resources for teachers and parents that can be used to assist children with disabilities in their studies.

"We are examining several factors that can influence the implementation," said Esquivel, who is currently completing her Master of Science degree. "But so far, we have seen that students may improve their performance by using both strategies compared to only observing the teacher or a peer doing the manipulation."

The team is expecting to finish the study this year. Once completed, Adams hopes to have a better understanding of the benefits of assistive technology in the classroom as well as a compilation of resources that can be provided to teachers, clinicians and parents.

"Teachers and other individuals directly involved in teaching students with disabilities lack access to appropriate information, equipment and support for planning and assessment. We want to change that."

For more information about the work happening in the Assistive Technology Lab, visit their website.