A Conversation with Christine Conciatori

Christine Conciatori, Director of the University of Alberta Museums.

Today I sat down to speak with Christine Conciatori, the Director of the University of Alberta Museums unit, about the nature of museum work.

Craig Neaves (CN): Just to get started, can you tell me a bit about yourself, and how you got involved with museum work?

Christine: I’m originally from Montreal, born and raised, but both my parents were immigrants. As a kid, the only two places I really felt comfortable were libraries and museums. I felt these were my spaces, as an introverted, shy kid. I realized that you could study to be a museum professional - and why not? I’m a visual thinker, and I felt that it satisfied that need. My first job was through a Young Canada Works program, and I worked in an archaeology lab for a summer. I eventually realized I loved exhibitions.

CN: What impact does the University of Alberta Museums (UAM) have on our campus?

Christine: It’s kind of a diffuse impact that not everybody sees and realizes, because we're a unit and the collections are everywhere on campus. Sometimes the culture or the paintings that we see become a background, and people don't notice how they improve our lives in the visual aspect until they are removed. The other impact is that the collections on campus are used for research. For me, that’s extremely exciting.

CN: Is there anything about the UAM that makes it unique compared to other museums?

Christine: The diversity of the collections. I think here, the quality and the intensity of research across 30 collections is unique. The Anne Lambert Clothing and Textiles Collection is the third largest and most important in the country. The Mactaggart Art Collection is one of the best of its kind in North America. The Meteorite Collection is also one of the largest in the country. All of this seems to not be known, and I would like people to realize that this is extraordinary, and a rare opportunity.

CN: What do you think the future might hold for the UAM?

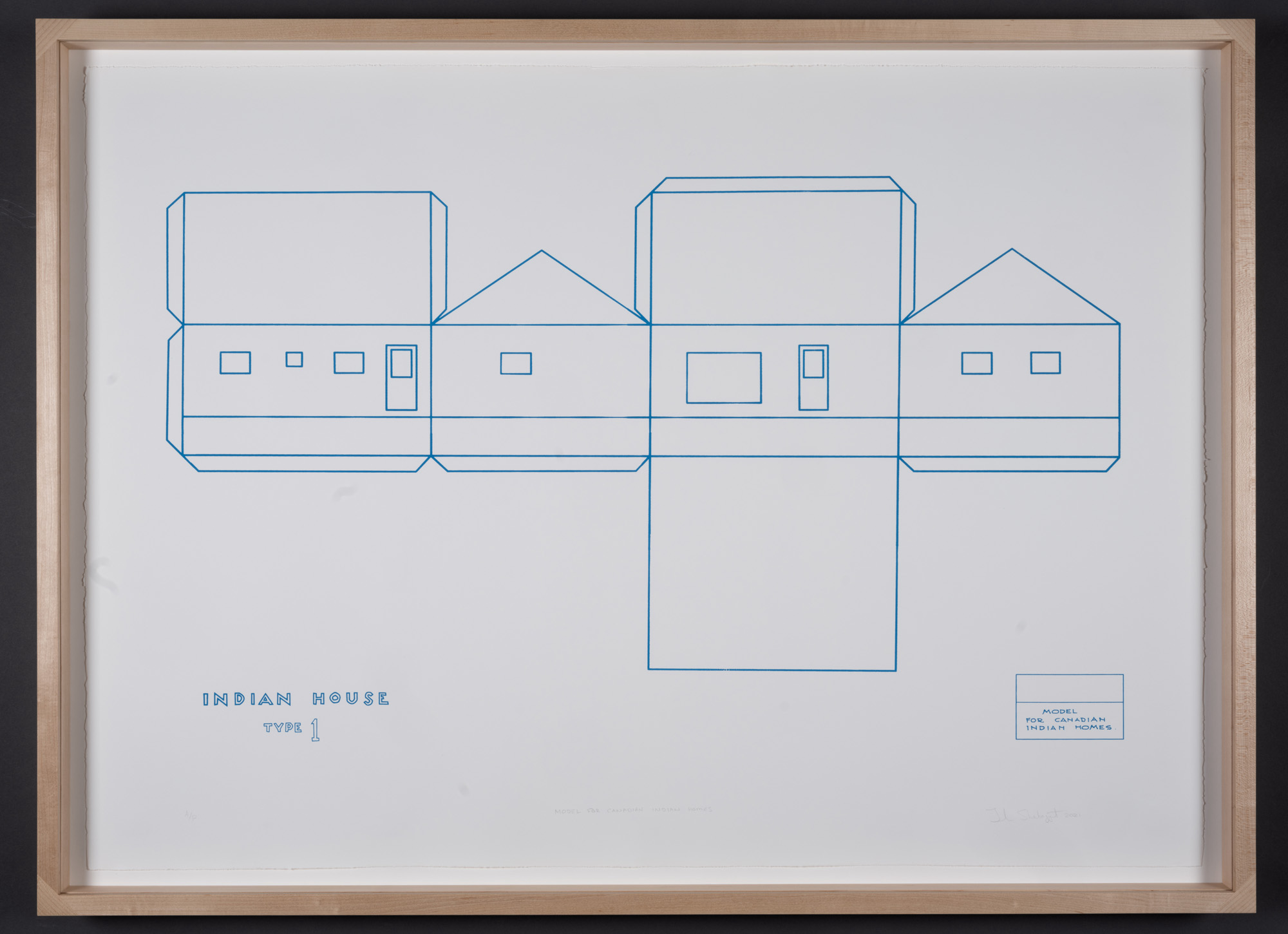

Christine: Like any other museum, we have the Truth and Reconciliation report, and we can see from the Canadian Museum Association their excellent Moved to Action they produced. We need to change our ways of doing. We need to change our way of thinking. We need to recognize forms of knowledge other than the traditional Western ways.

CN: Absolutely. What do you think are some challenges for the UAM, both now and in the future?

Christine: For all museums, especially since the pandemic, resources are a challenge. To preserve collections, you need specific environments, security - a lot of things. It's a highly specialized world. I’ve been in the museum world for 20 years, and when I started my career, in museum conferences the question was “What is the museum of the future?” It still hasn't been answered fully, because it’s changing. There's a lot of demand for museums now to be open, to be less elitist, which I totally agree with. If people feel that they can’t come because it’s not for them, you’re failing at your mission. So I think it's a big challenge not just to change preconceived ideas of what museums are, but to deliver on that.

CN: It’s almost like a paradox, where museums have to focus on the past while looking towards the future at the same time.

Christine: Exactly. You have to be open to listen. I’m glad I’m now in a management position, because it's good for me to support people who have new ideas, and who maybe haven't been trained in the traditional model of museums. I know that they will be more innovative than I can be, and as a manager, I have to recognize my own limits. Just because something worked in a museum ten years ago doesn’t mean it’s relevant now.

CN: How does the UAM work to promote things like diversity, inclusivity, and accessibility?

Christine: That's a good question. Museums are colonial institutions, and from the Western world, so I think it’s our duty to say, “We’re going to involve more people.” Accessibility is to be in contact with different communities both on-campus and off-campus, and to not make it sound like it is only for people who know what they are doing.

CN: What are the best parts of your job, and how is it different from other jobs in the UAMU?

Christine: Well I’m lucky, because I work with everyone from the team. I’m somebody who's very oriented in relationships with people. It’s a great team here, so I have fun getting to know them and see what they're doing. So for me, that's the best part, working with other people, and the curators, and the other divisions. I think the diversity of my job is nice, and I think after a while, I’m happy that I don’t have to be in the details of everything. Now when I have meetings, I can look at the plan and just make suggestions.

CN: What do you think the role of students is within the UAM?

Christine: For us, it's about, “Can we show you what museum work is, and give you some skills that you can apply in museums, but are also transferable to something else?” You help us with a lot of projects because we have small teams. But for me, it's also to get the perspective of young people who have not been in the field. I’ve been in this field for so long that you get used to seeing things one way, and you can’t make change yourself. You need to listen to those new voices because what we’re doing is for you, and what I leave when I retire will be what you integrate. So for me having the perspective of students is very, very important.

CN: How can I, as a student Collections Assistant, make the most of my experience? Do you have any advice for me?

Christine: Be curious. Ask questions. That’s always what I say. And don’t hesitate to say if you think there’s another way of doing something. We get so overwhelmed with work that we tend just to do things the same way, so sometimes we must take the time to stop, pause, listen, and go, “Oh yeah!” That’s why it’s important to have students and young people working, because we need new ideas and new ways of seeing things.

CN: I just have one more question, and that is, is there anything else at all you would like people to know about museums?

Christine: They’re not dusty. They’re not old. If you see a place that has an exhibition that’s been there for 20 years, they know, it's just they didn't have the money to change it. They are fun places, and places you can discover, and the thing is, you don’t have to read everything when you go to a museum. Just enjoy the ride when you go there, and stop at what interests you. It’s not an exam, and nobody’s going to test you at the end. Nobody’s judging, or checking that you have the background context knowledge before you get in. They’re just happy you’re coming.

Note: This interview has been edited for length. The full version will be posted at a later date.

Reflection

So museum work is easy, right? You collect objects, you preserve them, you display them.

Well, not exactly. If my conversation with Christine taught me anything, it’s that now is not the time to be complacent and continue previous colonial practices. This is true for any institution, but particularly for those that are meant to accurately represent the past. And how can we do that well if the very system we use is biased against different demographics or cultures?

We start from the beginning. We include new voices, and old ones that should have been included all along, and ensure moving forward that museums are kept responsible for involving all communities and being more than a storage facility. It’s tricky work, daunting even, but it also doesn’t mean the whole thing should be thrown away. As Christine wholeheartedly expressed, one can love museum work and be passionate about its continuation, while simultaneously acknowledging its flaws. In fact, it is only by addressing these flaws that we can truly get anywhere. I can see from my short time with the UAM that everyone here is dedicated to making these changes, and that is what really matters.

There’s a rabbit hole waiting here that anyone could easily jump into. During my time in the Vascular Plant Herbarium, for example, I learned about the complexity of a single specimen. It’s just a dried wildflower, right? But wait a minute - where did that specimen come from? Whose land or territory? Did the collector get permission? We have information on its Western uses - but what about its properties or medicinal uses for Indigenous Peoples? And that’s just considering one single aspect.

See what I mean?

As I touched on in the interview, there’s a puzzle to be solved here; one of the missions of museums is to preserve the past, but you can’t get stuck in the ways of the past either. I went into this conversation expecting to learn about what museum work is, and came out with a much more difficult question: how should museum work be done?

If you’re as curious as I am and want to dive deeper, make sure to stay tuned for the next interview. I’ll see you then!