A Conversation With Jennifer Bowser

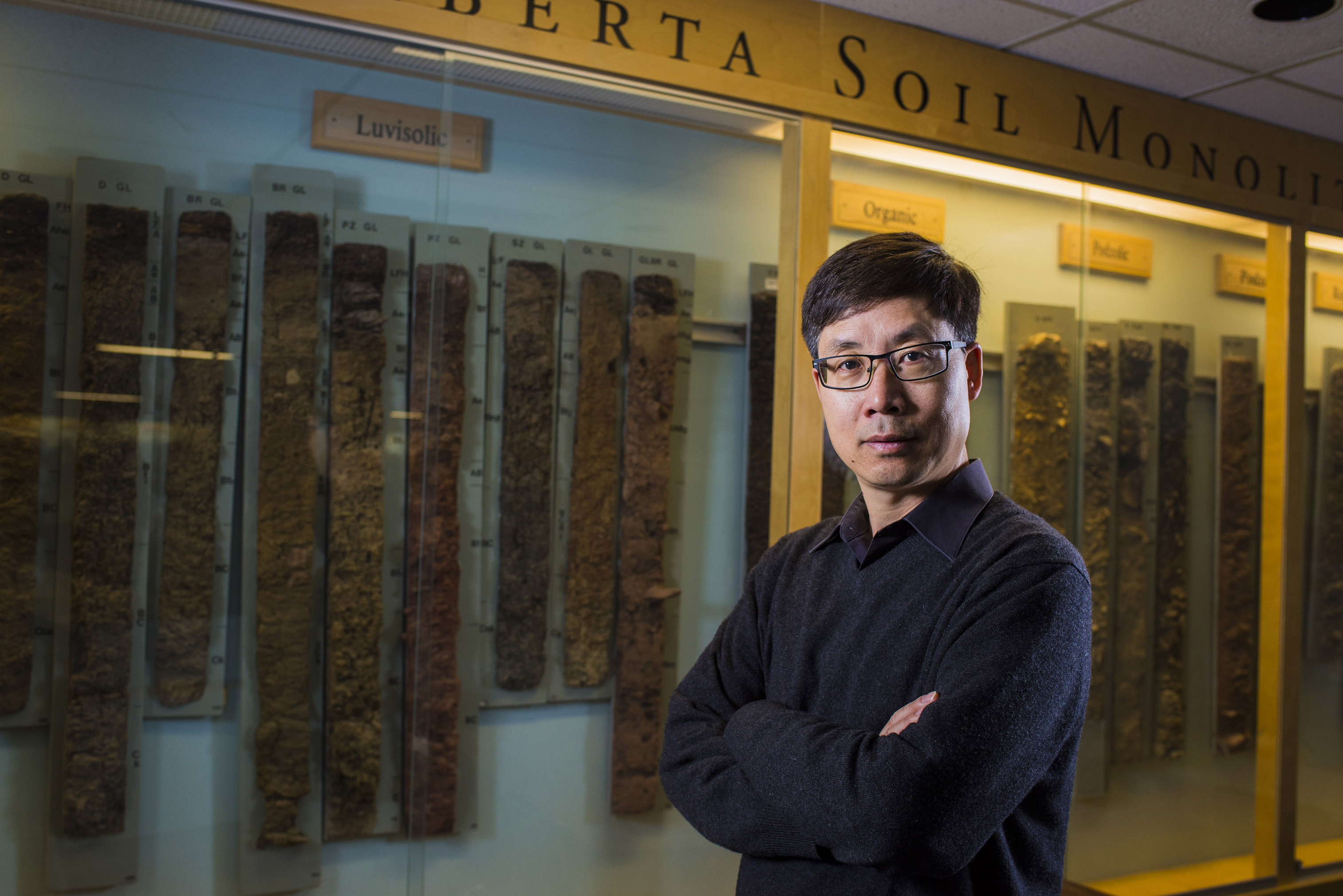

Jennifer Bowser, Moveable Cultural Property Advisor

Craig: Just to get started, could you tell me a bit about yourself and how you got involved with museum work?

Jenn: My title with the University of Alberta Museums (UAM) is Moveable Cultural Property Advisor, which is a mouthful. Essentially, my role is to make sure that registered museum collections are following legal and ethical best practices, that we’re abiding by university policy, and provincial, national, and international laws and regulations.

I did an undergraduate in honors history at the University of Winnipeg, and while I was there I was volunteering at the Manitoba Museum, and was also an intern at the Buhler Gallery. That's really where I discovered my love for hands-on museum work, and so from there, I went on to complete Fleming College’s Collections Conservation and Management program, which is a postgrad diploma.

Craig: During my interview with Christine, I talked a lot about the relationship between the UAM and the U of A campus, but I was wondering if you could tell me about the relationship between UAM and the broader community, within Edmonton and the province.

Jenn: The relationship between the UAM and the community is really based on reciprocity. For the UAM to succeed, we need the community to believe in us, to support us and our mission. For the community, we exist to help them understand their relationship, and their impact, on the cultural and physical worlds. Our unique role as a museum structure is to build a bridge between research and the community, be it through object-based learning in a classroom, outreach programs, exhibitions, loans, access to the data, and access to the objects themselves.

Craig: Could you tell me briefly what cultural property is, and why it is significant?

Jenn: The importance of cultural property is that the physical objects are a tangible representation of our culture, of our place in the world, of our environment; and the data that's associated with those physical objects is the intangible representation. There's lots to learn from the physical object itself, and even more to learn in some ways from the data associated with that object. Particularly in the natural science collections, the data that's associated with a particular specimen is crucial to us understanding the time and place of that specimen, and what it means in the larger, broader context of biodiversity, climate change, and evolution. I think the importance of cultural property in one sense is to help us understand who we are, where we came from, and where we're going.

Craig: What are some specific challenges you see dealing with moveable cultural property?

Jenn: Definitely mitigation of risk. Part of the purpose of museums is to ensure the long-term preservation of the objects and specimens in our trust, but we are a research institution, and our museum collections are research collections. So with that comes the need for access, to both the data and the physical object or specimen. And with that access comes a myriad of risks. So one of the challenges of moveable cultural property is trying to mitigate those risks, while also trying to balance the risk with the reward. We have these objects so that we can learn from them, and there has to be that level of interaction, while trying to minimize damage, so that those objects can be continued to be used.

Craig: Especially when dealing with cultural property, how do you handle ethical considerations? When you’re acquiring objects, and displaying them, and sometimes deaccessioning them, how does ethics play into that?

Jenn: It's so important. Ethics are our North Star when it comes to museum work. The thing about museums is that we don't own the objects. We hold the objects in the public’s trust. So the public is trusting us as an institution to care for the collections, care for their property, essentially. So ethics play a huge role in that because we have to be really conscious that we’re not doing anything that could cause harm to the objects, but also harm to the community. We have to have ethics because we have to maintain the public's trust in us. If we lose that, we've lost our purpose.

Craig: It's kind of like the objects aren't just objects themselves, they're representing something bigger; the community and the culture. It's not that you're just preserving the object, you're also preserving the bigger picture.

Jenn: Exactly. And the potential of the object as well. Advances in technology allow us to learn even more about an object that we maybe wouldn't have learned about 20 years ago when technology wasn't as advanced as today. But the advancement of technology is very unknown, and so there's always that potential of an object or specimen. So we don't want to do anything that could harm or limit that potential, and that future research that can come out of an object.

Craig: Because of the diversity of the collections, there are so many different types of objects. So how do you deal with care and handling? Because it's not the same process for, say, a painting, as it is for something from natural sciences.

Jenn: It's very collaborative. We work with the curators and the collections staff and the teaching assistants. We need to understand their use of the collections, their purpose for the collections, and from there, it's that balancing act of “these collections are here for their research, for their teaching, and how do we balance that access with care and handling?” There are certainly some general maxims that apply across the board to museum collections, but then there's also the unique uses and the unique attributes of a particular type of object. A meteorite is going to be treated very differently from a textile. Understanding the needs of the material is one thing, understanding the needs of the collection and the people who are using the collection is another aspect.

Craig: What is a project you're excited about, either going on right now or in the future?

Jenn: There's a lot to be excited about. We’ve got some collections that are working really hard on decolonizing their spaces, which is really exciting, and so important. Then you have more of this front-and-center research that's coming out of our collections, whether it's new dinosaur discoveries, or research that's driven by the impact of climate change on biodiversity. Something that's really, really important and very dear to me is the return and reburial of ancestors, which has been a long time coming. There's a loan that I’m working on for an international exhibition in Cleveland, which is very exciting for the Mactaggart Art Collection. And then there are various collections moves and collection upgrades that are happening as well.

Craig: How can I, as a student Collections Assistant, make the most of my experience? Do you have any advice for me?

Jenn: Be open and inquisitive, ask us, “Why?”. You're young, but you come with a very unique path, with experiences that are unique to you, and you have so much to offer us. You have a wealth of ideas, so don't be shy to question us, or to speak your ideas out loud. I think students in general often forget that yes, you are gaining experience and skills, but we are also gaining something from you with this opportunity, be it new ideas or ways of thinking, or taking a moment to reflect on the bigger picture on why we do things.

Craig: I just have one last question. Is there anything else you'd like people to know about museums?

Jenn: Museum work is incredibly rewarding. There is nothing I would rather be doing, anywhere in the world, than this work. I think that most museums can say that the work is challenging, it's complex, and we need community support. We're here for the community. In our particular circumstance, we’re a distributed network of museums across campus, in different disciplines, departments, and faculties. I think I’d like people to know that we are here for them, and to take advantage of that opportunity.

Note: This interview has been edited for length. The full version will be posted at a later date.

Reflection

Imagine you’re walking on a tightrope, holding a balancing pole in your hands. On one side of the pole is a weight called Long-Term Preservation. On the other side is a weight called Access and Research. Your goal is to get to the other side of the tightrope, to a place called Fulfilling the Object's Potential.

Now don’t freak out just yet, because luckily there are experts like Jenn who can help you on your way. One of the main challenges in helping a museum function indefinitely, as Jenn addressed, comes from the need to carefully balance the risks and rewards of utilizing museum objects. You want to preserve an object as best as possible so that it maintains its integrity and has useful data, not just for now, but for years down the road when humanity inevitably creates new technology that can bring to light more detailed information. On the other hand, you still have to allow access to museum objects, whether that be for exhibits, loans, or especially for a university, research, so that they can provide benefit in the present.

I got a taste of this dilemma firsthand while helping set up a tour in the Mactaggart Art Collection. While transporting the luxuriously made textiles, many of which are at least 200 years old, I admit to briefly wondering, “Why not just lock them away, where they will never have even the slightest risk of damage?” But of course, this would defeat the purpose of museums. If you can’t learn from an object, or interact with an object, then why have it in the first place?

The real trick to keeping your balance is adopting best-practice care and handling methods. Yes, there are inherent risks to storing museum objects, but this does not equal unavoidable damage. The best way to navigate these risks is by being proactive, which means acting before any threat to the collections even has the chance to occur. Vigilance is key. Even little things, like setting pest traps, sweeping floors, and not leaving lights on make a huge difference in the end.

It’s complex, it's challenging, it's a balance - but as Jenn emphasized, it's also incredibly rewarding.