For some students, school can feel like the furthest thing from a “safe space.” As anyone who has gone through the K-12 system can attest, school is sometimes a site of persistent anxiety and antagonistic social interactions that can follow students from the classroom to the home—especially in the age of social media.

“The way that hate lives with students and the way it can be such a crushing and suffocating force—it becomes all consuming,” says Jason Wallin, associate professor of curriculum and youth culture in the Faculty of Education’s Department of Secondary Education. “Forget all the other parts of school. I remember enough about being a teenager to remember that much.”

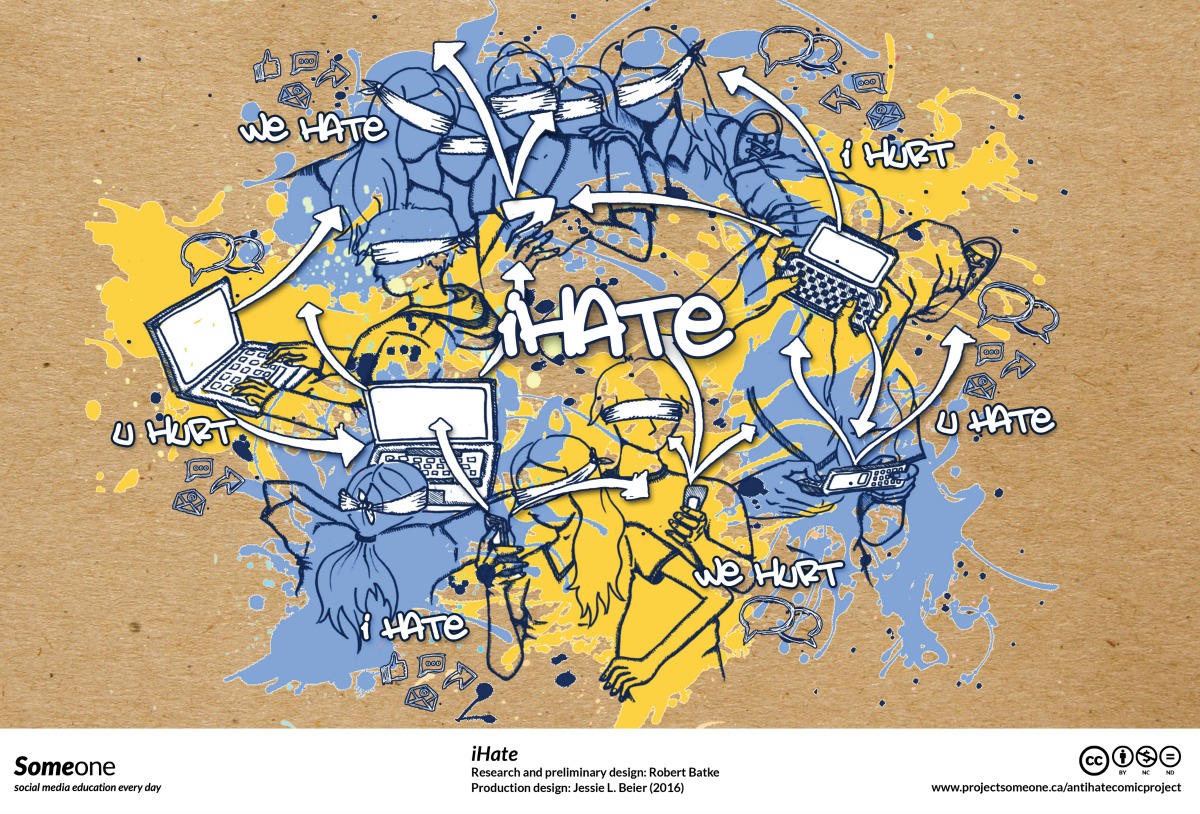

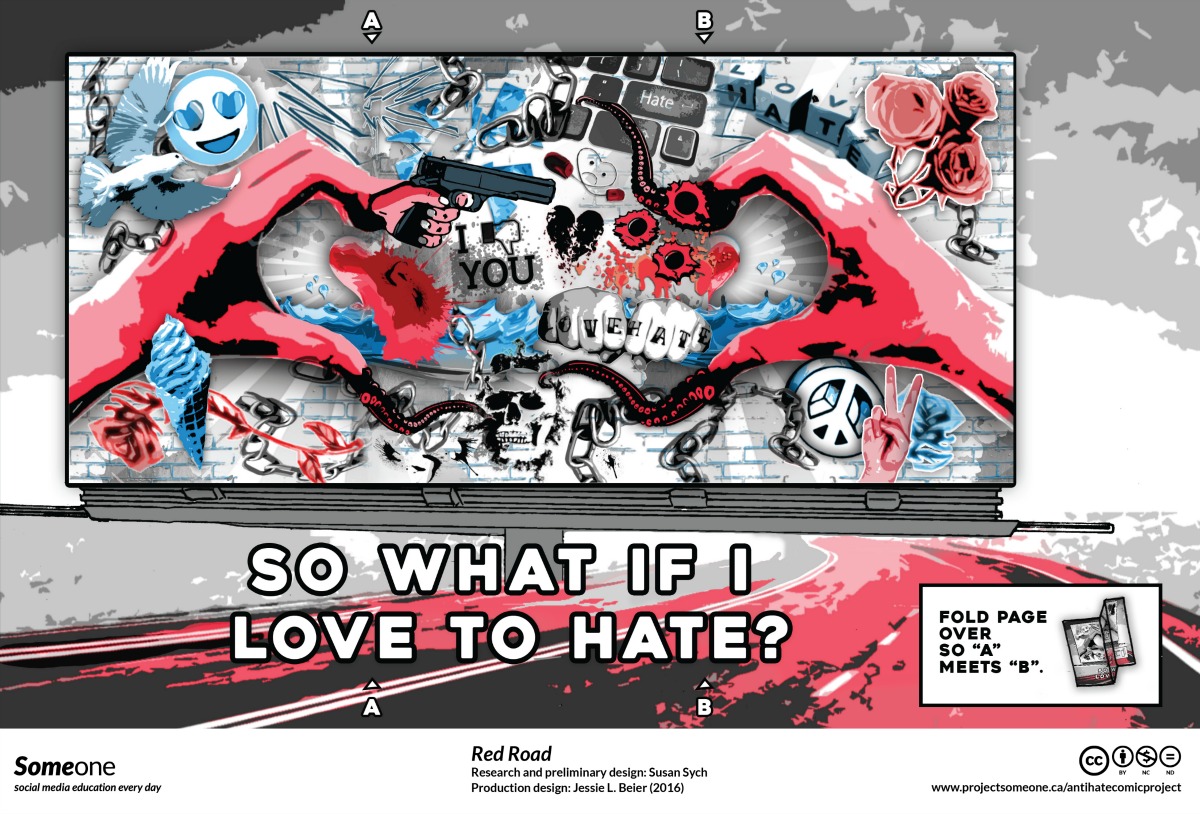

An anti-hate comic project

Hateful attacks are particularly damaging when they are made against a young person’s racial, cultural, gender or sexual identity. The large, instantly accessible audience provided by social media platforms makes things that much worse.

“What has become common sense on social media often carries underlying messages of discrimination and alienation,” says Wallin. “It also has the staying power to last forever. If someone attacks you online, there is an archive of it that can be brought up at any time. There are no take-backs.”

Although many of these conflicts take place outside of the classroom, Wallin wants to help teachers move the conversation about hate and hate speech into the curriculum with a graphic resource for teachers. Learning to Hate: An Anti-Hate Comic Project is designed to help pre-service and practicing teachers discuss tough topics such as cyberbullying, microaggressions and harmful labelling with their students.

The comics are a part of Project Someone, an anti-hate pedagogy initiative based at Montreal’s Concordia University that involves more than 20 collaborators across Canada.

Learning to Hate: An Anti-Hate Comic Project from Someone Project on Vimeo.

After Wallin’s experience with a graduate course focusing on graphic novels, he knew he wanted to incorporate comic books into this project.

“Comic books are a successful medium in terms of reaching people with its ease of communication,” Wallin says. “Anyone can pick it up and engage with it. And that’s what we wanted for these comics––we wanted them to produce questions. That was our major intent with these comics––to create resources that would catalyze conversation around how hate lives and is encountered by youth today.”

Research produced by students in another one of Wallin’s graduate courses was ultimately translated into comic book format by artist and Faculty of Education doctoral student Jessie Beier.

“The goal was to really focus on youth experiences and what youth have to deal with daily in terms of small instances of discrimination and hate,” Beier says. “I worked with lots of different formats––for some I created infographics, some are like comic book pages, there’s a Mad Magazine-style fold-in. I drew on a lot of popular culture and things I see online, what I think youth are engaging with, the formats they’re familiar with, turning those on their heads so people have to look closer and see that those platforms are maybe not so neutral.”

Wallin plans to use the comics in his classroom with his undergraduate students in the hope that these materials will inspire the next generation of teachers to find their own ways to start the discussion with students about hate speech.

“These teachers don’t necessarily need to use the comics,” he says, “but they can take on their own process as a way to begin to uncover a curriculum that is often quite hidden in schools.”

Watch an interview with Jessie Beier and Jason Wallin of University of Alberta about Learning to Hate: An Anti-Hate Comic Project on Vimeo.

Feature image: Illustration from Learning to Hate: An Anti-Hate Comic Project (2016).