More than four decades ago, one of the most contested episodes in Canada’s history began at Sir George Williams University in Montreal.

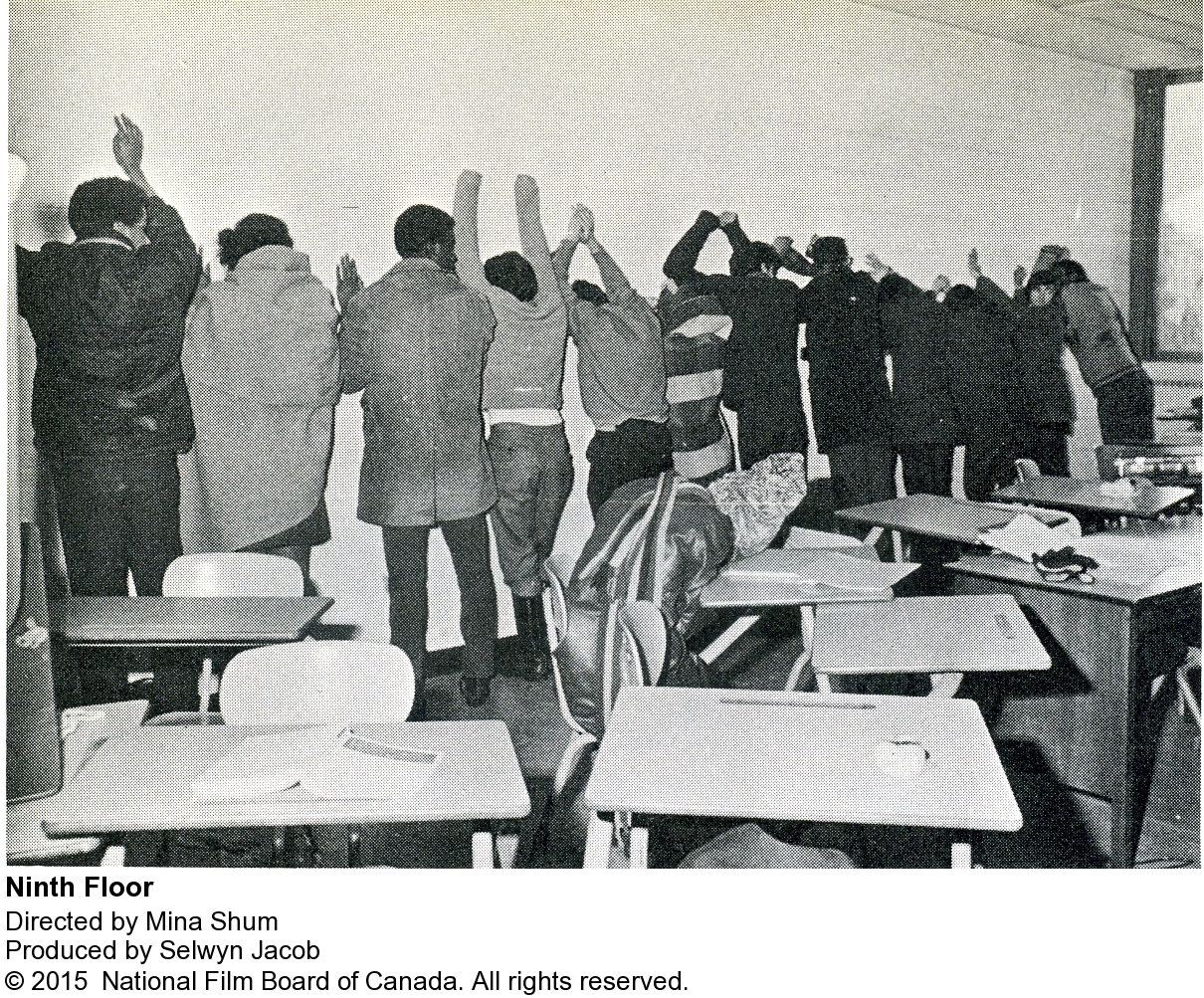

It started quietly, when a group of Caribbean students at the school (now a part of Concordia University) began to suspect one of their professors of discrimination because of unfair grading. The suspicions then became formal accusations of racism, which were mishandled by university administration, and students occupied the university computer lab on the ninth floor of the Henry F. Hall Building in protest.

Selwyn Jacob (‘70 BEd) was an education student at the University of Alberta when the Sir George Williams protest turned into the largest student occupation in Canadian history. For decades, the award-winning documentary producer has wanted to make a film about the incident. In February 2014, Jacob and acclaimed director Mina Shum began shooting Ninth Floor in Montreal.

The National Film Board documentary had its world premiere at the 2015 Toronto International Film Festival and will be screened at Edmonton’s Metro Cinema (8712 - 109 St.) on Saturday, January 30, at 7 p.m. with Selwyn Jacob in attendance.

Jacob answered a few questions about Ninth Floor in anticipation of the film’s local screening. This interview has been edited for length.

Q. I read in the Montreal Gazette that you were a student at the University of Alberta when the Sir George Williams protest happened in 1969 and that it had a profound impact on you. Were people talking about it here in Edmonton at the time, or did you find out about it later?

A. I arrived in Canada in September 1968 to attend the University of Alberta. This incident occurred in February 1969, and even though it took place in another calendar year, I had still only been in the country for just over five months.

I heard about the events in a very curious way, through one of my professors from the U of A. When he heard that I was from Trinidad he would often try to involve me in the classroom discussion by trying to get a Trinidadian perspective on whatever topic we might have been talking about. I went so far to invite him to one of our Caribbean dances, and he came. So we became very close.

Then one morning, during his introductory remarks, he turned to me and said, “Selwyn, I hope we’re still friends.” I was puzzled by the remark, and it was only later when I heard the news about the Montreal incident, that I understood where his comment was coming from.

I remember attending a presentation at the Students’ Union Building at which Rosie Douglas, one of the key personnel in the narrative, was speaking. This would have been in the winter of ‘69 or ‘70. Rosie is the character who was eventually deported, and subsequently became Prime Minister of Dominica. So the event was well known among students and university personnel at the time. I am not sure about the general populace at the time—my world revolved around the U of A campus.

Q. Why was it important to you that this film be made?

A. I have always felt a direct connection to the story. A number of friends from my home village in Trinidad were studying at Sir George Williams at the time, and I could have easily ended up there myself. But a good friend of mine from Trinidad had studied at U of A, and he encouraged me to come to Edmonton.

Over the years I have heard so many diverse perspectives about what really triggered the event and pondered so many unanswered questions, e.g. How come I never heard about this event? Why has it remained untold for so long? Why were the Caribbean students seen as troublemakers both here and in their home countries? Why are some of the participants so reluctant to talk about it? What would I have done if I had been a student at Sir George? In a way, my goal was to set the record straight by speaking to individuals who participated in the event, and other people whose lives have been—and continue to be—impacted by the event.

Q. Although the protests chronicled in Ninth Floor happened 47 years ago, the subject matter—race relations on university campuses—is very timely. In the U.S., university campuses both big and small have recently seen a number of protests around issues of race (e.g. University of Missouri). Here in Canada, the issue of making post-secondary institutions more accessible and welcoming to First Nations, Métis and Inuit students is in the news. What do you think we can learn from the Sir George Williams protests today, in 2016?

A. We can view the Sir George Williams affair as a cautionary tale in the sense that we should do a lot of self-reflection before we pre-judge people for no other reason than the fact that they may look, dress, speak, and behave differently from the rest of “us”. Respect other people’s opinions, and give them the opportunity to express themselves.

Q. Before you pursued film studies at the University of Southern California, you received a BEd from UAlberta’s Faculty of Education—does your background in education inform your filmmaking?

A. I think that my background in Education and my love for history and research serve me in good stead when I embark on any film project. I am very meticulous with details, and I feel that I have an obligation to get the story right. As a producer I sometimes find myself working with emerging filmmakers, and I feel like am functioning as a teacher—not in a classroom context, but in a teaching context nonetheless.

Q. What stories do you want to tell next?

A. I am currently developing a short film which is inspired by the memories of residential school survivor Lena Wandering Spirit, who lives in Fort Chipewyan, Alta. The filmmaker, Jay Villeneuve, who is Cree from Alberta, will tell her story using a mixture of shadow puppetry, interpretive dance, Aboriginal music, ballet, and painting, to tell the story of how she has coped with the experience over the years.

I am also working on two photo-essays which are part of a series being produced by the NFB across Canada in commemoration of Canada’s 150th anniversary. One is set in Yukon and the other in Vancouver, and they will both deal with the theme of legacy and immigration. They will be ready for January 2017.