One of the artifacts from Margaret Mackey’s childhood is a picture book about Santa Claus that’s part of her earliest memories. She describes it as a cheap little thing printed on flimsy paper with no discernible literary merit. But when she recently found a copy and flipped to a page depicting kids making Christmas cookies, Mackey says the image stirred an internal experience she could scarcely put into words.

“Holding that book in my hands, I remembered things—the smell of the kitchen as I was holding this book in my hands 60 years ago—very nebulous associations, but very potent,” says Mackey, a professor in the Faculty of Education’s School of Library and Information Studies (SLIS).

“It was like an explosion in my head of neurons that hadn’t been activated in decades until I looked at that book. It was breathtaking.”

This experience, which was part of Mackey’s research for a forthcoming book reflecting on the texts that shaped her as a reader, contributed to her growing curiosity about the influence of location on the formation of literacy.

The power of the auto-bibliography

“I looked at my school textbooks and my novels and picture books, the magazine subscriptions we had and the TV programs, the cookbooks and knitting patterns, the Sunday school materials and the exhibits in the museums I went to—as broad a collection of materials with which I became literate in St. John’s, Newfoundland in the 1950s as I could come up with many, many years later,” she says.

“The more I thought about it, the more I realized that the bit about St. John’s in the 1950s was also crucial and that although literacy in some ways means you participate in a global conversation, in other ways it’s very local, and so I got interested in the local side of things, the ways in which literacy is shaped by where a child becomes literate.”

In working on the book, entitled One Child Reading: My Auto-Bibliography (to be published in April 2016 by University of Alberta Press), Mackey says she created maps of her hometown overlaid with notations about the special places of her childhood and the texts that informed them. Intrigued by the results, Mackey initiated a pilot project with graduate students in SLIS to have them create similar depictions—a process she says enhanced their eloquence in talking about the connections between spaces and texts.

“The students came up with some fabulous and interesting maps,” she says. “What the map does is provide a container for the juxtaposition of materials that kids encounter, and the space holds them side by side in ways I haven’t been able to get at before.”

Support for curiosity-driven research

An Insight Grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC)—along with support from the team at the Faculty of Education’s Research Innovation Space in Education—will enable Mackey to take this research further.

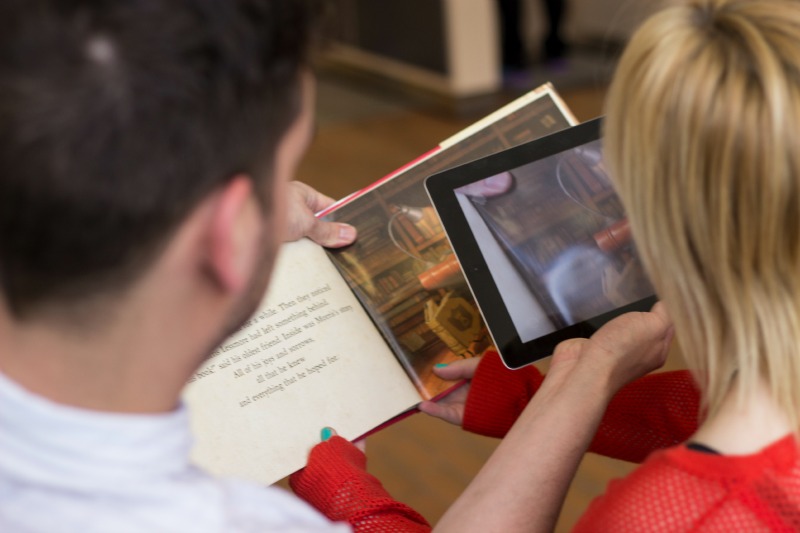

Her SSHRC-funded project involves working with undergraduate students to develop digital maps that relate places that were special to them in their childhood to the texts that shaped their print, media, and digital literacy, even those places that have no physical location.

“One of the things I’m interested in is my childhood was almost entirely outdoors, but kids today don’t get to go out in nearly the way kids in the ‘50s and ‘60s did, and so one of the options for people—and it was taken up by some of the pilot participants—is that the space they put on their map can be a fictional space. Because, for sure, some kids are more familiar with a fictional territory than they are with their own neighbourhoods.”

While the change in how children experience their physical environs and the impact of the digital realm on the formation of literacy are highly relevant areas of inquiry that may have helped her secure the grant, Mackey credits SSHRC for supporting research that allows scholars to follow their curiosity and arrive at questions they may not have previously thought to ask.

“All my research life, my question has been a version of ‘What can we find out if we set up some interesting juxtapositions of some textual materials, let some interpreters loose on them, and see what they have to say that we haven’t been considering in our other kinds of research?’” Mackey says.

“I think this kind of very open-ended research about literacy, which is a very internal and private achievement as well as a public one, gets to notions about literacy that other kinds of research don’t reach. The social question about children who don’t play outside is an important one, but SSHRC is also happy to say go ahead and see what you can find out.”