Shaolin Kung Fu: A Jewel of China’s Living and Breathing Cultural Heritage

What often springs to mind when we, as Canadians, imagine Chinese culture? Perhaps we think of the breathtaking Great Wall of China, or we could be reminded of the wonders of Chinese cuisine, which has integrated itself into - and likewise been influenced by - the multicultural tapestry of Canada’s vibrant food landscape. However, one of the greatest examples of China’s living and breathing cultural heritage that has attracted global fanfare is Shaolin Kung Fu, which has been practiced and continually developed by the Buddhist Monks at the Shaolin Temple in central China for nearly 1500 years. The story of Shaolin Kung Fu surpasses its proud martial arts tradition and tells us about an ancient Buddhist monastery, nestled in the lofty peaks of the sacred Mount Song, which has had a profound impact on Chinese culture.

Historical Background of Shaolin Kung Fu

Buddhism has had a deep and lasting impact on the development of Chinese culture, often being referred to alongside the indigenous Chinese belief systems of Confucianism and Taoism as “the three converged doctrines” (sanjiao heliu).[1] Although Buddhism originated on the Indian subcontinent, it was brought to China during the Western Han Dynasty (202 BCE-8 CE) and was slowly embraced and spread among Chinese society.[2] While it initially clashed with Taoism and Confucianism, Buddhism was progressively adapted to Chinese culture and developed in accordance with China’s unique context.[3]

Regarded as the home of Chan Buddhism, the distinctively Chinese strand of Mahayana Buddhism, the Shaolin Temple played a pivotal role in developing Chinese Buddhism.[4] In 496 CE, the devoutly Buddhist Emperor Xiaowen (r. 471-499 CE) of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-535 CE) established the Shaolin Temple near his capital city of Luoyang (located in modern-day Henan Province), and appointed the Indian monk Buddhabhadra (known as Batuo in Chinese) as the monastery’s first abbot.[5] The monastery assumed great religious significance with the arrival of another foreign monk, Bodhidharma (known as Damo in Chinese), who initiated Chan Buddhism in China and became its very first patriarch.[6] For that, the Shaolin Temple is regarded as the birthplace of Chan Buddhism, better known in the West by its Japanese name - Zen Buddhism.

Regarded as the home of Chan Buddhism, the distinctively Chinese strand of Mahayana Buddhism, the Shaolin Temple played a pivotal role in developing Chinese Buddhism.[4] In 496 CE, the devoutly Buddhist Emperor Xiaowen (r. 471-499 CE) of the Northern Wei Dynasty (386-535 CE) established the Shaolin Temple near his capital city of Luoyang (located in modern-day Henan Province), and appointed the Indian monk Buddhabhadra (known as Batuo in Chinese) as the monastery’s first abbot.[5] The monastery assumed great religious significance with the arrival of another foreign monk, Bodhidharma (known as Damo in Chinese), who initiated Chan Buddhism in China and became its very first patriarch.[6] For that, the Shaolin Temple is regarded as the birthplace of Chan Buddhism, better known in the West by its Japanese name - Zen Buddhism.

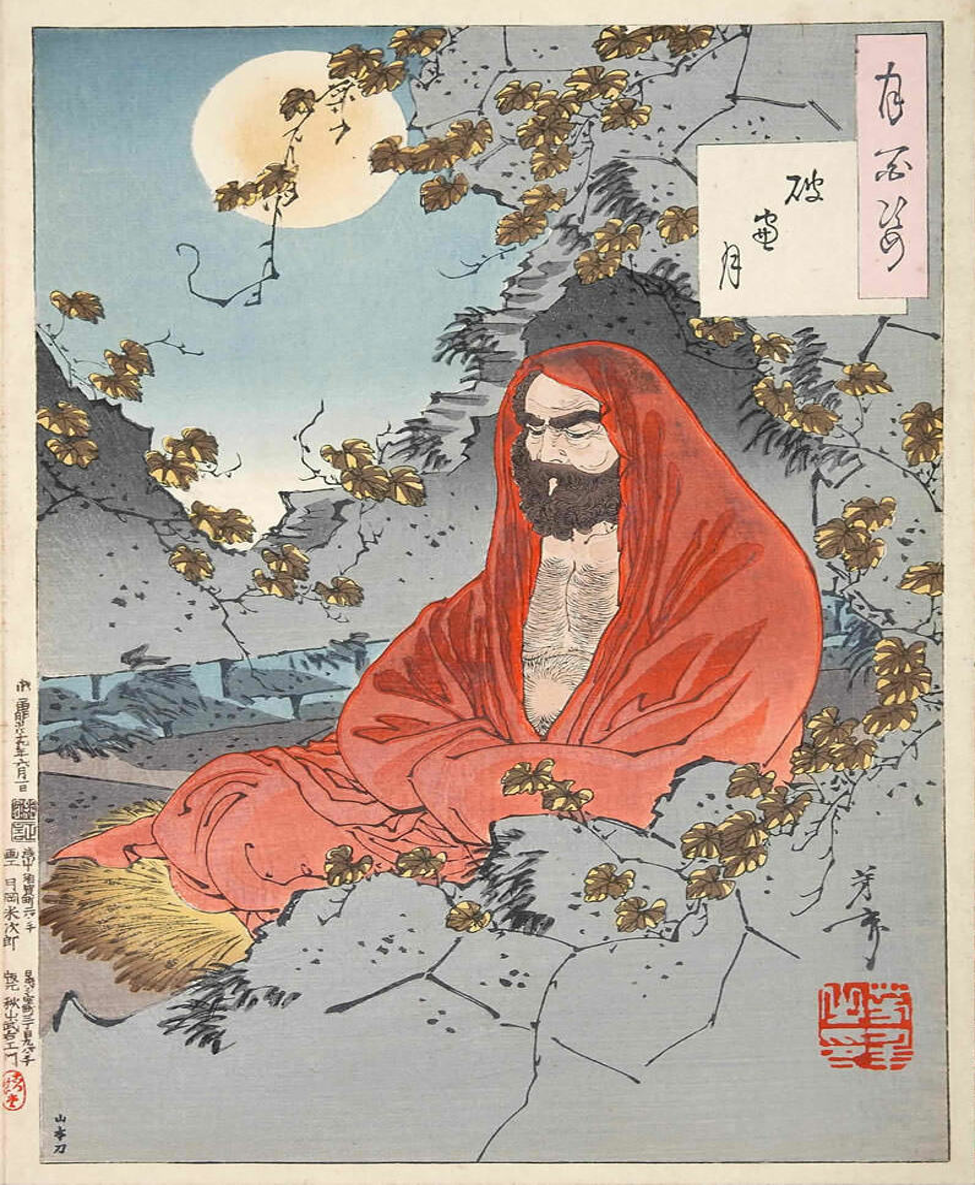

“The Moon Through a Crumbling Window,” 1887, by Japanese artist Yoshitoshi, depicts the first Chinese patriarch of Chan Buddhism, Bodhidharma (Damo).

“The Moon Through a Crumbling Window,” 1887, by Japanese artist Yoshitoshi, depicts the first Chinese patriarch of Chan Buddhism, Bodhidharma (Damo).

From the very inception of the monastery, martial arts were a key part of the Shaolin monks’ daily lives. Batuo’s famous disciplines, Sengchou and Huiguang, both practiced and perfected martial arts at the Shaolin Temple.[7] However, as the cultivation of martial arts evolved over the centuries, they came to assume a very prominent role in the culture of the Shaolin Temple. The Shaolin martial arts tradition largely started as a pragmatic response to the demands of the time, but would progressively evolve into a practice inextricably linked to Chinese culture and Buddhism.

Firstly, martial arts were viewed as both a form of necessary exercise for the monks (made essential due to long periods of sitting in meditation), and as a form of spiritual meditation in and of itself, with an emphasis on the discipline and focus inherent to martial arts training.[8] Secondly, the many political conflicts that arose in China over the years forced the Shaolin monks to use martial arts as a means to defend themselves and the monastery.[9] This eventually led to them offering their military services to friendly state patrons, notably under the Tang (618-907 CE) and Ming (1368-1644 CE) Dynasties.[10] As such, the Shaolin monks, through their dedication to martial arts, left a significant impact on Chinese history, in addition to Chinese culture.

Although the Shaolin monks participated in military campaigns during most of the Tang Dynasty, they likely did not develop their own unique form of martial arts until the 12th century CE.[11] In the period from the 12th-16th centuries CE, the Shaolin monks acquired great expertise in staff fighting, earning a reputation as the most capable staff fighters in all of China.[12] Then, at the beginning of the 16th century, the Shaolin monks started to cultivate their own unique form of unarmed hand combat (quan).[13] As this process has continuously evolved through to the modern day, contemporary Shaolin continue to master and develop the now-world-renowned Shaolin Kung Fu.[14]

It was in the 1980s, during the process of political and economic liberalization under Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping, that the Shaolin Temple and its martial arts truly started to capture the modern cultural psyche.[15] As the monastery and its warrior-monks were prominently featured in many films, starring actors like Jet Li and Bruce Lee, the Shaolin Temple itself became a popular attraction.[16] Many Chinese and foreign tourists alike started to travel to the monastery, seeking to visit the iconic location and even learn the skills of legendary Shaolin Kung Fu.[17] In recognition of the Shaolin Temple and its martial arts having become a prominent symbol of Chinese culture internationally, the monastery was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2010.[18]

Shaolin Kung Fu, Chan Buddhism, and Everyday Lessons for Canadians

Considering Buddhism’s strong opposition to violence, the synthesis of martial arts and Chan Buddhism (known as “martial Chan” (wuchan) by its practitioners) may appear paradoxical.[19] However, as the Shaolin Temple’s current abbot, Shi Yongxin, aptly put it, “The initial purpose of introducing martial arts to Shaolin Temple was to protect the Temple. In the language of our monastic community, it was to protect the Dharma. However, in the process of development, martial arts became a powerful tool for spreading the Dharma. Hence, it is said, ‘The name of the Temple is renowned for its boxing, and the boxing reveals the glory of the Temple.’”[20] In that sense, not only does Shaolin Kung Fu illustrate the unique Chinese characteristics of Chan Buddhism, but its popularity also acts as a vehicle for spreading Buddhist teachings, known as the Dharma.

The Venerable Shi’s comments ring especially true in the context of the event featuring Shaolin Kung Fu at CIUA. While the exhibition will undoubtedly attract many Canadians who are well acquainted with the mythologized imagery of stoic monks practicing martial arts in mountainous monasteries, it will give them deeper insight into ancient practices and principles that they may apply in many facets of their daily lives. Shaolin Kung Fu, and the attendant spiritual messages and historical heritage of its warrior-monk practitioners, can teach us, as Canadians, many important lessons that can enhance our daily lives.

First and foremost are the obvious health benefits. In addition to the physical activity that Shaolin Kung Fu requires, the meditative side of the practice, including focused breathing techniques, has also been proven to improve mood and increase cognitive function.[21] In terms of less tangible benefits, the spiritual teachings of Chan Buddhism help us to better cope with adversity by encouraging us to accept all circumstances and challenges encountered in our lives.[22] Chan Buddhism teaches us to “live in the world”, but in a manner that increases inner peace and happiness.[23]

Finally, the story of the Shaolin Temple and Chan Buddhism offers a fascinating glimpse into the enduring legacy of ancient intercultural contact and collaboration; China’s rich Buddhist history is a telling example of the long-lasting results of the deep exchanges between Indian and Chinese cultures. As today’s modern Canada stands as a multicultural society that fosters interactions and learning among diverse cultures from around the world, working together harmoniously to shape the nation’s identity, the history of the Shaolin Temple and Chinese Buddhism underscores that such intercultural collaboration is not unique to Canada. Indeed, our country is simply contributing to a continuous and greater human story of cultural contact, tolerance, and diversity that has existed since ancient times.

Finally, the story of the Shaolin Temple and Chan Buddhism offers a fascinating glimpse into the enduring legacy of ancient intercultural contact and collaboration; China’s rich Buddhist history is a telling example of the long-lasting results of the deep exchanges between Indian and Chinese cultures. As today’s modern Canada stands as a multicultural society that fosters interactions and learning among diverse cultures from around the world, working together harmoniously to shape the nation’s identity, the history of the Shaolin Temple and Chinese Buddhism underscores that such intercultural collaboration is not unique to Canada. Indeed, our country is simply contributing to a continuous and greater human story of cultural contact, tolerance, and diversity that has existed since ancient times.

Many Canadians have had the pleasure to visit and see the built legacies of other cultures - the Colosseum, the Taj Mahal, and the Great Wall of China, just to name a few. Notwithstanding all of their beauty and value, the Shaolin Kung Fu event at CIUA offers something that those monuments cannot: a living, breathing and interactive piece of our shared global cultural heritage. Come to CIUA to experience Shaolin Kung Fu and Chan Buddhism with Master Shi Yandi on August 3rd to participate in the continued development of one of China’s richest cultural traditions!

REFERENCES

- Su, Xiaoyan. “Reconstruction of Tradition: Modernity, Tourism and Shaolin Martial Arts in the Shaolin Scenic Area, China.” The International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 33, no. 9, 2016, 934.

- Chong, Tian. “The Influence of Buddhism on the Formation and Development of Shaolin Culture.” Pakistan Journal of Social Research, vol. 5, no. 2, 2023, pp. 1124-26.

- Ibid., 1126.

- Ibid., 1125.

- Shahar, Meir. The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts. University of Hawai’i Press, 2008, 17-18.

- Ibid., 12-14.

- Ibid., 9.

- Sukhoverkhov, Anton, et al. “The Influence of Daoism, Chan Buddhism, and Confucianism on the Theory and Practice of East Asian Martial Arts.” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, vol. 48, no. 2, 2021, pp. 235–36.

- Chong, Tian. “The Influence of Buddhism on the Formation and Development of Shaolin Culture.” Pakistan Journal of Social Research, vol. 5, no. 2, 2023, 1126.

- Su, Xiaoyan. “Reconstruction of Tradition: Modernity, Tourism and Shaolin Martial Arts in the Shaolin Scenic Area, China.” The International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 33, no. 9, 2016, 935.

- Shahar, Meir. The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts. University of Hawai’i Press, 2008, 3.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Su, Xiaoyan. “Reconstruction of Tradition: Modernity, Tourism and Shaolin Martial Arts in the Shaolin Scenic Area, China.” The International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 33, no. 9, 2016, 939.

- Shahar, Meir. The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts. University of Hawai’i Press, 2008, 1.

- Su, Xiaoyan. “Reconstruction of Tradition: Modernity, Tourism and Shaolin Martial Arts in the Shaolin Scenic Area, China.” The International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 33, no. 9, 2016, 939.

- Ibid., 943.

- Shahar, Meir. The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts. University of Hawai’i Press, 2008, 1.

- Chong, Tian. “The Influence of Buddhism on the Formation and Development of Shaolin Culture.” Pakistan Journal of Social Research, vol. 5, no. 2, 2023, 1126.

- Chan, Agnes S., et al. “Shaolin Dan Tian Breathing Fosters Relaxed and Attentive Mind: A Randomized Controlled Neuro-Electrophysiological Study.” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2011, 2.

- Hershock, Peter D. Chan Buddhism. University of Hawai’i Press, 2005, 2-3.

- Su, Xiaoyan. “Reconstruction of Tradition: Modernity, Tourism and Shaolin Martial Arts in the Shaolin Scenic Area, China.” The International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 33, no. 9, 2016, 935.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chan, Agnes S., et al. “Shaolin Dan Tian Breathing Fosters Relaxed and Attentive Mind: A Randomized Controlled Neuro-Electrophysiological Study.” Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2011, pp. 1–11.

Chong, Tian. “The Influence of Buddhism on the Formation and Development of Shaolin Culture.” Pakistan Journal of Social Research, vol. 5, no. 2, 2023, pp. 1124–1132.

Hershock, Peter D. Chan Buddhism. University of Hawai’i Press, 2005.

Shahar, Meir. The Shaolin Monastery: History, Religion, and the Chinese Martial Arts. University of Hawai’i Press, 2008.

Su, Xiaoyan. “Reconstruction of Tradition: Modernity, Tourism and Shaolin Martial Arts in the Shaolin Scenic Area, China.” The International Journal of the History of Sport, vol. 33, no. 9, 2016, pp. 934–950.

Sukhoverkhov, Anton, et al. “The Influence of Daoism, Chan Buddhism, and Confucianism on the Theory and Practice of East Asian Martial Arts.” Journal of the Philosophy of Sport, vol. 48, no. 2, 2021, pp. 235–246.

Author

Daniel Lincoln

Policy Research Assistant

Daniel is a recent graduate of the University of Alberta, completing a BA With Distinction in Political Science, Economics, and History. Daniel also received a Certificate in Globalization and Governance that he completed in conjunction with his undergraduate degree. His primary research interests include Russian and Chinese foreign policy, international trade, security policy, and Canada's geopolitical and economic role in the Arctic.