I have always been fascinated by understanding the human-environment relationship and how changes in the landscape can affect the way we experience that reality. In the last six years, I focused on this aspect as I explored the social changes brought on by oil and gas extraction in a region where little research on this topic within my discipline (anthropology) has been done.

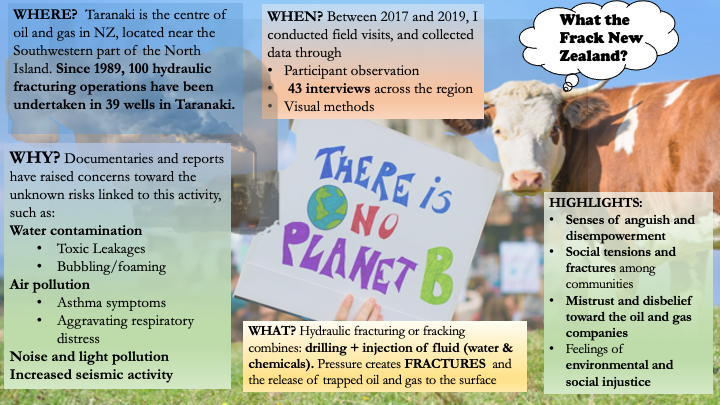

Often, the first image that comes to mind when thinking of New Zealand is a calm and serene green landscape with sheep and cows grazing freely. Not many people are familiar with the presence of the oil and gas industry in the country, and in particular the use of hydraulic fracturing, or fracking— an unconventional and controversial extractive practice. Fracking combines vertical and horizontal drilling along with the use of a fracking fluid, a mix of water, sand and assorted chemicals, injected into the ground at high pressure. This combination creates small fractures within the rock, described at times as tiny earthquakes, and it leads to the release of the trapped oil and gas to the surface. Worldwide, fracking has been widely contested, as reports and documentaries have raised concerns on the environmental and health risks associated with it.

In the region of Taranaki, where I have carried out my ethnographic research, fracking has been occurring since 1989. More than 100 fracks have been done, with companies often sharing land with farmers, or fracking close to houses and schools. Once I found out about how long fracking has been conducted in New Zealand, I started to ask myself: What are the changes people may have been experiencing because of it? How do the modifications occurring in the landscape may affect people’s sense of belonging and the way they interact with the environment? Through my fieldwork— I spent a total of seven months living in Taranaki— I immersed myself in the landscape, engaging with community members, Maori iwi and hapu representatives, farmers, professionals in the hydraulic fracturing sector, and activists to better grasp their experiences. I interviewed anyone interested to share their experience and perspective with me. Many community members and several activist groups have questioned the roles of institutions and local governmental bodies through the years and different governmental administrations, expressing their discontent from participating in marches to building complex legal cases against the petrochemical industry and local councils. Through their stories, I have grasped the polarizing aspects of this practice and how the extensive use of fracking operations has led to social friction among members of the same community, as well as within families and circles of friends.

People I interviewed have expressed the need to bridge the gap between those who work in the sector and the locals who are affected. With my research I hope to help give a clearer understanding of what fracking does to communities and families, unveiling the risks and living conditions experienced by those living in fossil fuel-dependent regions, hearing directly from those affected. Their stories can promote changes in policies by knowing what has worked and what has not and open a dialogue between all people impacted, not just in their region but also globally with other communities facing similar problems.

To me, innovation is about having an outlook on the future. Innovation is linked to the idea of creativity and having an attitude that fosters a positive change. This doesn't mean one must create something completely new or extraordinary, leaving people speechless. An innovative person is also someone who applies a new perspective, a fresh perspective to something others might be already familiar with. In the moment you question what exists, you are already innovative and capable of bringing something new. Despite not being as knowledgeable about fracking as an engineer might be, I looked at a landscape I was familiar with and I felt a connection to, and my curiosity pushed me to investigate more in-depth, through my lens and perspective, and understanding that everyone’s view of the world is unique to oneself.

The University of Alberta's inaugural Digital Innovation Showcase features the research of graduate students and postdoctoral fellows. View posters and engage the presenters on Twitter May 10-14, 2021 #UAlbertaInnovationShowcase.

Anna Bettini

Anna is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Arts, Department of Anthropology under the supervision of Dr. Andie Palmer. Anna was born in a small town outside Milano, Italy and has had the opportunity to travel and learn more about other cultures and languages, igniting her interest in anthropology. When she was 16 years old, she embarked on a study abroad program in New Zealand, and from that moment an interest in and love for the country started. After finishing high school in Italy, Anna moved to the United States and attended Central Washington University and graduated in 2014 with a double bachelor’s degree in Primate Behavior and Ecology and Anthropology. She continued to explore topics in anthropology and completed a Master’s in Social Anthropology in the United Kingdom at the University of Kent in 2015. She is now at the end of her program at the U of A, waiting for her next adventure.