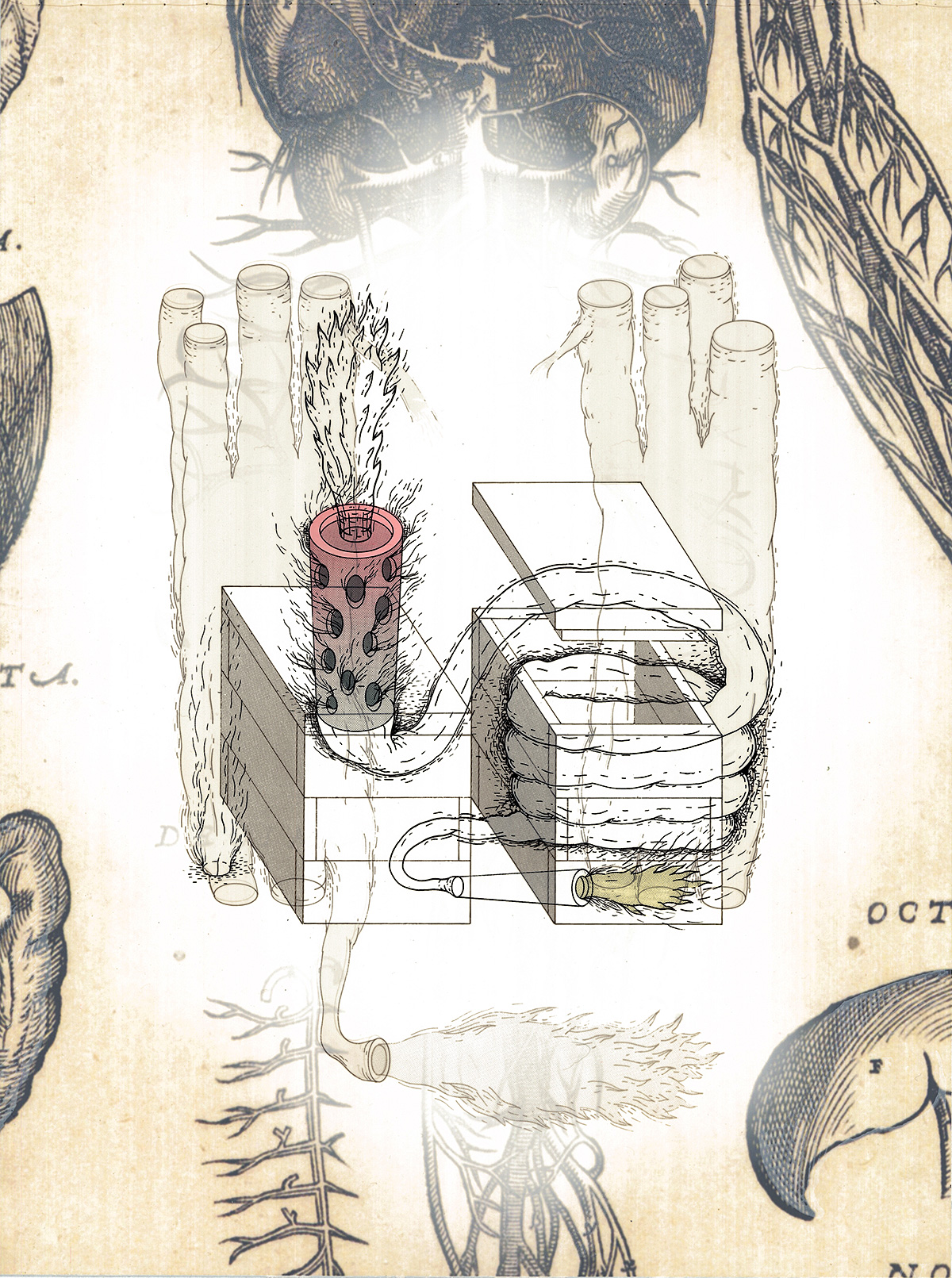

Virus #1 by Sean Caulfield, '92 BFA, '96 MFA

Take a moment to examine this piece of art. Certainly you noticed it when you opened this page - it is, after all, a striking image - but then, like most readers, you probably jumped right to the headline, looking for more information.

So now go back to the image and take the time to really look at it. Examine the colours, the layering. Take in the different elements and how they are working together. Think about what the image means to you.

Now, how does that meaning change when I tell you that this work of art is called Virus #1? Are you rethinking how you interpreted each of the elements? One more detail: this image was created for a book called The Vaccination Picture. As you process that last bit of information, examine once more what you think this piece of art is trying to convey.

It's probably safe to say that with every new detail, you moved further away from your own interpretation and closer to understanding the artist's intention. This is the magic of words and images, says Charity Slobod, '10 BA, '10 Cert(Trans), '15 MA.

"Words help anchor the image and bring context and meaning to a more universal understanding and the author's intention," says Slobod, who studied Canadian comic book translation for her master's in Modern Languages and Cultural Studies.

An image by itself has a very open meaning, she explains. The vascular system might mean one thing to a nurse and something completely different to an engineer. But once you add words alongside the image, the meaning becomes narrower, more closed.

In the case of the images you see below, the artists are graduate students seeking to capture the essence of their academic work in one striking image, with a title and short description. This expertise-stretching task was set before them in the Images of Research competition, organized by University of Alberta Libraries and the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research. More than 100 students submitted images in 2017, and New Trail is featuring the winning entries.

Why ask researchers to turn their work into images? Academic writing can sometimes be a barrier when researchers share their work with the public, says Slobod, who works with the professional development team for the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research. Art can invite conversation with non-experts in a way that academic studies in peer-reviewed journals can't.

"The production of art gives people access to think about [the topic] in a broader way," says Sean Caulfield, '92 BFA, '96 MFA, Centennial Professor of Fine Arts. He created Virus #1 and other pieces for The Vaccination Picture, a book by his brother, Timothy Caulfield, '87 BSc, '90 LLB, director of the U of A's Health Law and Science Policy Group. The book pairs art and science to debunk the myths about vaccinations.

"At a certain point, data don't change minds," says Sean Caulfield.

"Telling a story can open up dialogue. It can encourage viewers to look in a new way."

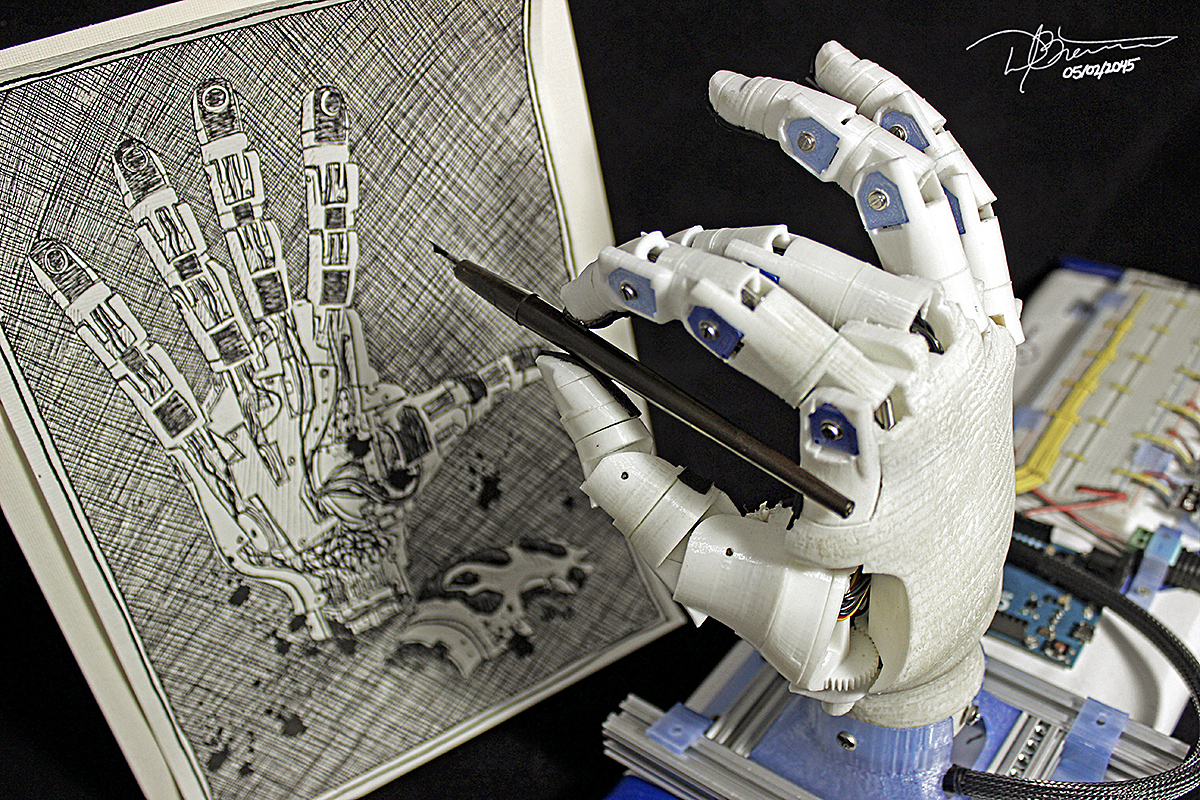

Self Portrait in 2045

First Prize (Tie)

Dylan Brenneis, '16 BSc(MechEng)

Master of science student in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering

Image created with Michael (Rory) Dawson, '08 BSc(MechEng), '11 MSc, Jaden Travnik, '15 BSc(Spec), and Patrick Pilarski, '09 PhD, in the Bionic Limbs for Improved Natural Control Lab, University of Alberta

The image depicts a robotic hand expressing its identity through self-portraiture, challenging the viewer to reconsider a prosthetic hand as merely a crude replacement. While this level of dexterity and intelligence is still beyond the capabilities of prosthetic limbs, it is entirely possible that in the future, such a self-portrait won't be far-fetched. The Bionic Limbs for Improved Natural Control (BLINC) Lab is dedicated to restoring lost limb function to amputee patients - not only physical movement but also sensations of touch and spatial orientation. My research focuses on creating devices such as the featured hand, which has a camera integrated into the palm, to change the way people think about prosthetic limbs. By including features such as on-board cameras, telescoping limbs or interchangeable tools, I am exploring what is possible when we don't restrict ourselves to humanoid forms.

I Am Not Alone

First Prize (Tie)

Camelia Vokey

Master of science student in the Department of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Rehabilitation Medicine

Image created by Artur Merkulov on Whyte Avenue, Edmonton

The eyes tell it all. In the company of a dog, this military veteran can begin to move beyond the debilitating memories and symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. My research explores the effectiveness of animal-assisted therapy in treating PTSD. All humans benefit from animal interaction, and the use of animals in therapy is growing. Spending time with dogs and other animals increases levels of the hormone oxytocin, which is associated with reducing stress, anxiety, sleep disturbances and social isolation. People yearn for the "free zone" that a dog provides - free from judgment, criticism, rejection, punishment, evaluation and unsolicited advice. For veterans, caring for a dog can decrease trauma-inflicted anxiety, loneliness, stress and anger. A dog encourages them to trust and feel safe again and helps them regain their self-confidence and self-esteem. This bond is not only a key to escape from desolation but also the beginning of a faithful friendship.

Wonder-Trail in Blue and Yellow

Third Prize

Noemi de Bruijn

Master of fine arts student in the Department of Art & Design, Faculty of Arts

Image created at Abraham Lake, Alta., and developed at the University of Alberta

My research focuses on our relationship with the environment. I'm concerned with what I call "nature-culture dislocation" - how we have distanced ourselves as a culture from the realities of the planet we live on. We curate everything that surrounds us, and photography is a great example of how this occurs in modern life. I use photographs, my own or those taken by others, and then embellish them using print, painting or drawing media. I also get inspiration from topographical maps, where the contrast of art and science reflects the dislocation I speak of in my research. By altering the horizon lines of the landscape, I hope to entice the viewer to have a second look and to reconsider what they are seeing in the imagery. When that happens, I feel that I have achieved a reconnection to the landscape and the land, and I believe that makes my work worthwhile.

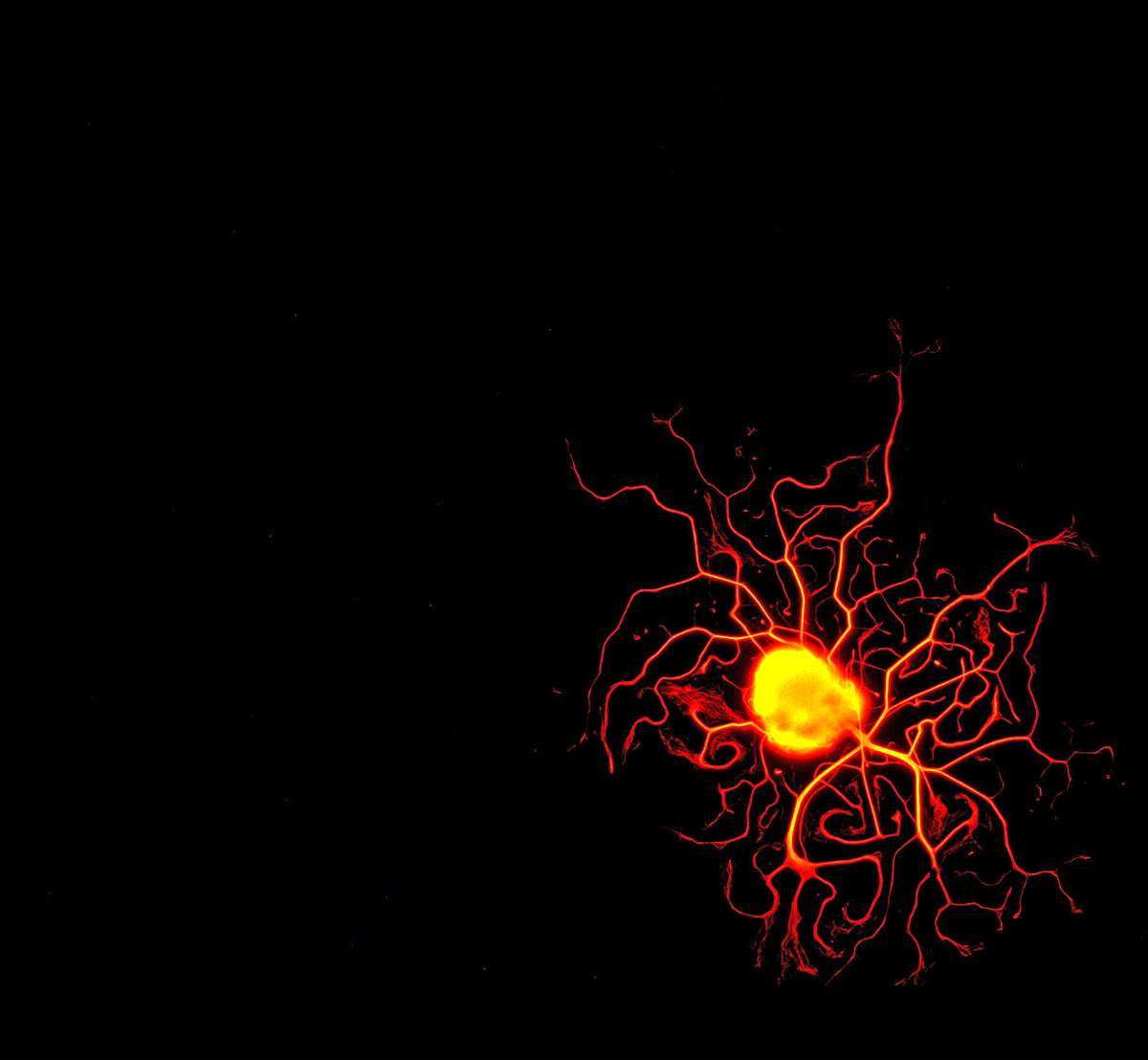

Outgrowth

People's Choice Award

Trevor Poitras, '16 BSc(Spec)

Master of science in neuroscience student in the Neuroscience and Mental Health Institute, Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry

Image created at the University of Alberta

The peripheral nervous system, a fragile network easily injured by trauma, damage or disease, is capable of regeneration but it can be limited and incomplete. My work involves investigating the biochemical pathway that may act as "brakes" in preventing the regeneration of axons - slender, information-transmitting fibres that project from a nerve cell. An example might be regulatory mechanisms designed to prevent cells from growing out of control. Finding ways to block these mechanisms could improve the growth of neurons and the chances of a functional recovery. This image shows a dissociated sensory neuron culture from a rat's dorsal root ganglion, which is being tested to determine whether drugs or particular molecules can cause neurons to grow new projections. These types of experiments are important for developing clinical treatments that can help repair peripheral nerve damage.

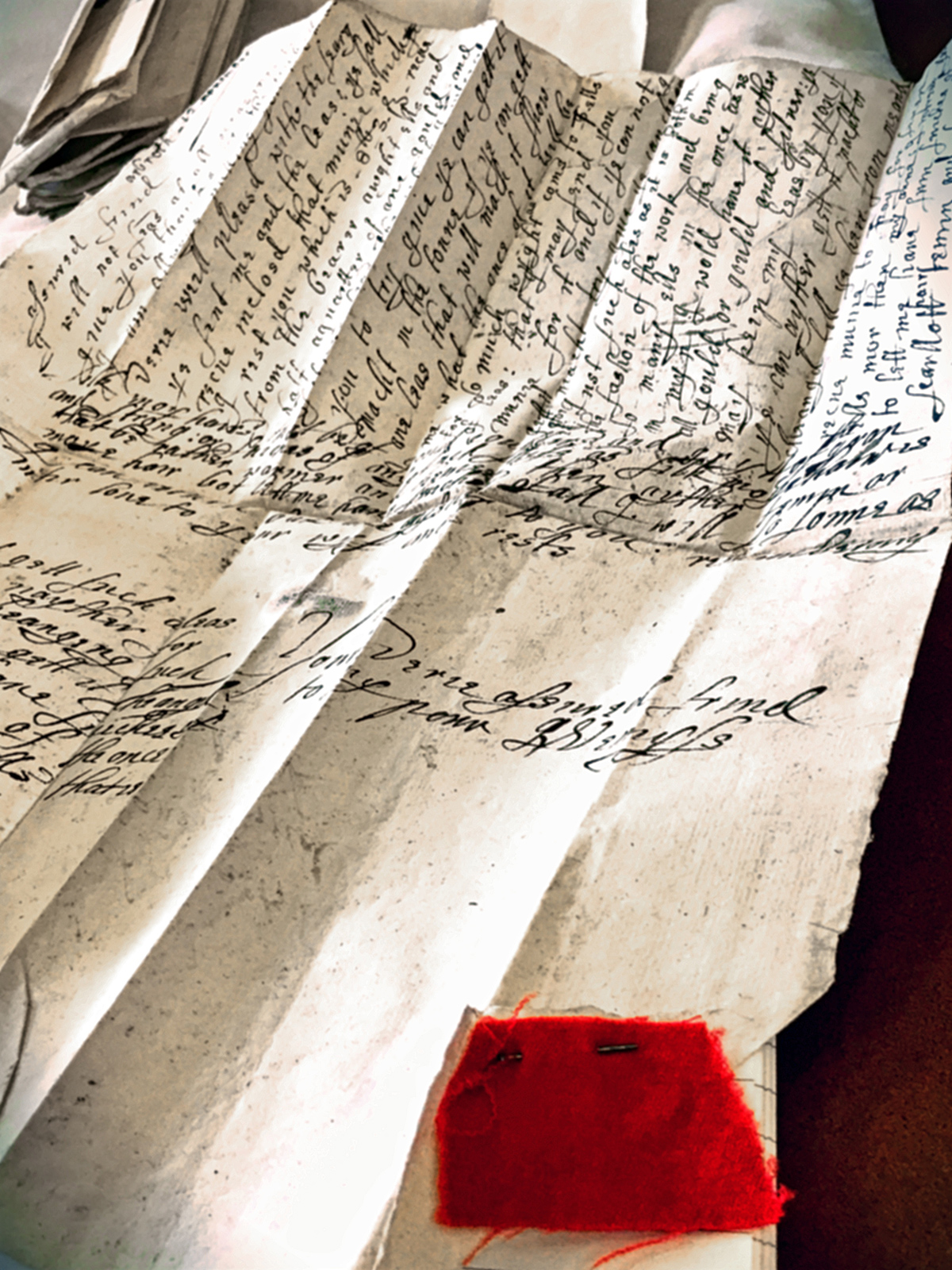

'Divers cullort ribbans': Material Evidence From the Archives

Honourable Mention

Ashley Sims, '13 MA

Doctor of philosophy student in the Department of History and Classics, Faculty of Arts

Image created in Edinburgh, Scotland

Historians rely overwhelmingly on written sources, interpretation and analysis to examine past events. My doctoral dissertation explores consumer behaviour in 17th-century Scotland. I use everyday documents that people created - diaries, household account books, receipts and letters - to understand how average Scots lived their material lives. This photograph illustrates a rare occurrence in my research, where both the written and material evidence exist in a single source. An Edinburgh woman wrote this letter in 1660 to a cloth merchant in London requesting "1 ell" (94 centimetres) of a specific red velvet ribbon. Generally, I can only imagine the particulars of the desired goods or hope something similar has survived in a museum. But 357 years ago, the writer included a cutting of the ribbon, giving me direct access to the object - and further connecting modern historian and historical figure. This photograph shows just how familiar and accessible the past can be.

Body as a Home

Honourable Mention

Camille Renarhd (Burger)

Doctor of philosophy student in the Department of Drama, Faculty of Arts

Image created with Jenny Abouav at the University of Alberta

La distancia que nos aproxima, "the distance that brings us closer," is a ritual dance piece dedicated to my friend Nadia Vera, a Mexican dancer, activist and anthropologist. Before her 2015 murder in Mexico City, Vera believed the arts could influence social transformation. My PhD focuses on Indigenous rituals and performing art, and this piece, created at the university's Arts-Based Research Studio, is a reflection of my interactions with other artists, Indigenous peoples, activists and scientists. In it, I explore an underscore of jumps and voice, finding physical and emotional engagement in a body that is resilient, explosive, alive. How can we continue to dance with a missing part of us - with our grief, our sadness - and transform it? Jenny Abouav took this photo as I was jumping in front of a blue square projection. My body is dissolving into the light, losing its human shape, transformed in an abstract landscape.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.