In 1982, the disease Houghton decided to tackle was known only as NANBH — non-A, non-B hepatitis, as in not caused by hep A or B viruses. A mysterious blood-borne disease defined by what it wasn’t. This would become his quest: to chase a shadow.

Together with Qui-Lim Choo, whom he recruited in 1983 along with Amy Weiner, Kang-Sheng Wang and Maureen Powers, Houghton set to work. One of the things that had slowed progress on NANBH — let’s call it HCV, the hepatitis C virus, since we know now that’s what they were seeking — was the lack of suitable animal models. Other than humans, hep C is only known to infect chimpanzees.

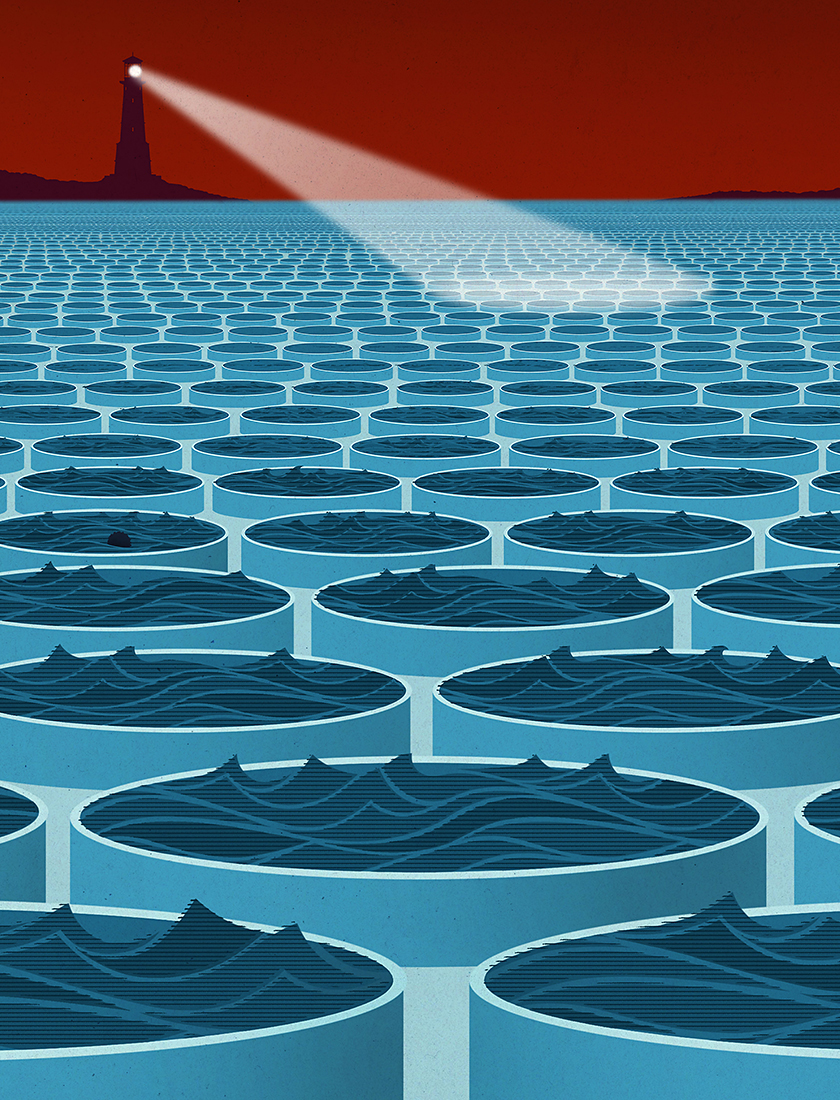

Houghton visited the lab of Daniel Bradley of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, an expert in the NANBH chimpanzee model. With Bradley’s collaboration, the Chiron team extracted nucleic acid (DNA and RNA) from infected chimps and patients and cloned them to create vast libraries containing millions of nucleic acid sequences. They began sifting through them for one that looked as if it didn’t belong — a task akin to finding a single typo in a dictionary.

These days, with modern techniques that vastly speed up the copying and sequencing of segments of the genome, virology is a different beast than it was then. Nothing in Houghton’s tool kit at the time was quite up to the scope of this endeavour. “The methods we were applying were not sensitive enough,” he says. If today’s technology had been available back then, Houghton says, “it probably would have taken seven weeks” to find the mystery virus and sequence it.

Instead, it took seven years.

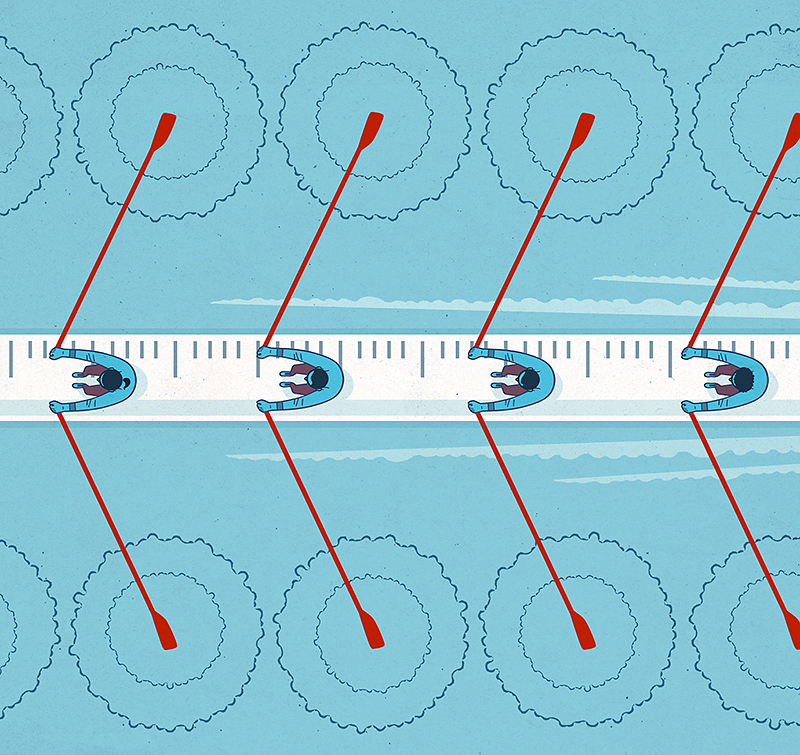

It didn’t help that no one really knew what kind of pathogen they were looking for. Was the virus like hep B or yellow fever — or even a prion? Or maybe it was a retrovirus like HIV. Houghton’s strategy was to go wide, trying many different molecular approaches at once based on the scientists’ best guesses. It was like fishing with multiple rods over the side, each hook carrying different molecular bait. At one point, more than 20 different approaches were in play.

Their work was painstaking. And fruitless.

“After two or three years,” Houghton says, “we were still shooting blanks.”

The path to any Nobel Prize is paved with failed experiments, almost by definition. The breakthroughs that win a Nobel tend to be innovations wrought by failures that force you to rethink and try new approaches.

One day in 1985, three years into the research, Houghton went next door to the lab of George Kuo to discuss a new approach Houghton had been considering involving the generation of monoclonal antibodies against HCV. That key discussion convinced Houghton to try an immunoscreening approach to bacterial clone libraries. At about the same time, Bradley suggested the same idea.

So, the Chiron team put another fishing rod over the side, so to speak.

The tactic, never before tried to identify a new virus, would use antibodies — proteins in the blood that bind to foreign substances — to help detect the virus. The team would copy the DNA and RNA from chronic hep C carriers into DNA in bacteria and make libraries of many millions of bacterial colonies. Then they could screen the libraries using samples from patients with chronic hep C.

If the idea worked, the antibodies would sniff out and bind to the foreign stowaway, the hep C virus, in a rare one-in-a-million colony.

Over the next couple of years, Houghton and Choo sifted through the cloned DNA and RNA in 11 different bacterial libraries — millions upon millions of genetic sequences. They found nothing at all that might be the elusive quarry.

Nothing.

It has been said that people, like teeth, come in two types: incisors and grinders. And surely this applies to scientists, too. Incisors make an early impact with a provocative paper, enjoy early fame and then often fade from view.

Houghton is unquestionably a grinder. People who’ve worked with him say he is like a dog on a bone. “What distinguishes Mike compared to other researchers is that he zeroes in on a goal and goes after it, and he just never lets go,” says John Law, lead virologist in the Li Ka Shing Applied Virology Institute and a research associate in the Department of Medical Microbiology & Immunology. “He’s not going to fall back on Plan B just because Plan A is hard.”

Back in 1987, after five years of trying and failing to find hep C at Chiron, Houghton was beginning to feel some pressure as the project leader responsible for the research. “The investors put pressure on management, and management put pressure on me.” Houghton knew he was close to being cut loose.

He didn’t particularly care. This was his mission: to fight the toll of disease on so many lives around the world.

“You can go ahead and fire me,” he remembers telling his boss. “I’ll just continue to work on this elsewhere.’ ”

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.