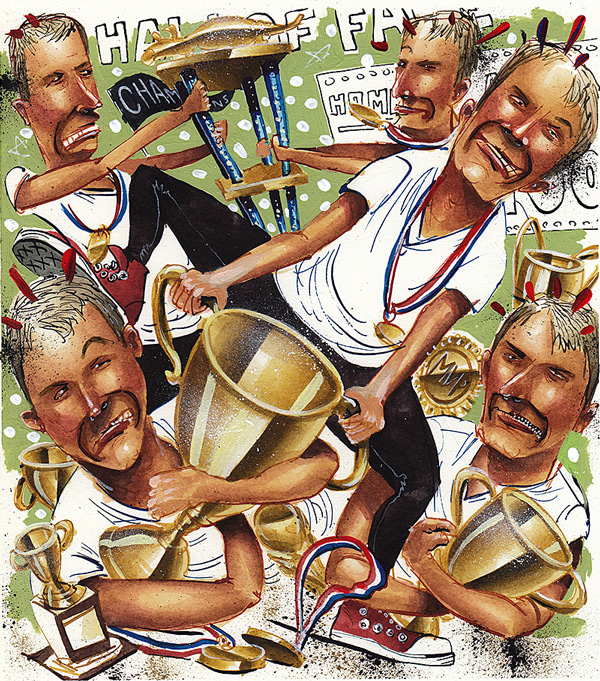

“Winning isn’t everything, it’s the only thing.” Vince Lombardi, the iconic coach of the 1960s Green Bay Packers, made that saying famous, and it was the mantra I grew up with, though I didn’t play football and had no idea who Lombardi was. I was, however, the oldest of six kids, five of us boys. We lived in a bungalow in northwest Calgary that was so cramped I didn’t have a bedroom to myself until I moved to Edmonton for university. The four oldest, all boys, were produced in a four-year window. We were about the same size and of equal athletic ability. These factors coalesced to create a ruthless Serengeti-like ecosystem where every day was a blunt fight for survival. If you weren’t a predatory lion, you were a dopey wildebeest about to become a meal. I lost the tip of my middle right finger in those years, and sometimes I imagine it happened during dinner once, when I got too close to the plate of a hungry brother.

In some ways, itemizing what we competed over on this pitiless savannah — some would call it a house — doesn’t warrant detailing, because if it had a physical, emotional, moral, existential, philosophical or comical element to it, we competed over it. Food, sports, clothes, jibes, insults, fights, laundry, bathroom time, phone time (there was just one landline in the house), TV channels, the best TV chair, the front seat in the car, the back seat in the car, the middle seat in the car, the radio in the car, driving the car. All that on top of the succession of contests that played out 24/7 on our basement pool table, our ping pong table (a piece of plywood on top of the pool table), our hockey rink (the basement floor by the washer and dryer), our basketball court (a hoop dangling from the garage), our golf course (four holes laid out around the yard played with a duct tape ball), our mountain bike route (the alley), our bobsled run (the hill behind the neighbourhood), and in the various games of poker, chess, checkers, Risk, Monopoly, hearts, cribbage and Scrabble. Perhaps most formative was the relentless race to score verbal points. Serving up the quickest and sharpest retort earned double points if the wisecrack made either parent laugh.

In case it’s not clear by now, our house was a wee bit competitive. Calling it sibling rivalry is like calling Taylor Swift a singer. It doesn’t quite do it justice. Competitiveness was omnipresent, ubiquitous, all-encompassing. I loved the cut and thrust of it and, to this day, when I’m back with my brothers (our sister was exempt) we still value a good insult. I spent years trying to convince my wife, Cathy, and then our two children, that this verbal jousting was my love language, an effort that mercifully yielded under the force of their amiability and good nature.

I suppose I grew up thinking “Serengeti mode” was natural. I mean, you can’t criticize a lion for biting things. It’s what lions do. When a brother displayed a millisecond of weakness, you pounced first and asked questions later — or never. It wasn’t until I began to mature, what, three, four years ago, that I began to realize competitiveness has a dark side. Writers like Somerset Maugham, Iris Murdoch and Gore Vidal have written versions of, “It is not enough to succeed. To be truly happy, one’s friends have to also fail.” Now that sentiment is competitive.

Multiple elements contributed to my shift in thinking. The first was probably that I began to underperform in athletic events. I couldn’t handle it when someone piled on the aggressiveness, and I couldn’t figure out why. My perception of myself as an athlete was that I could remain calm and handle whatever was thrown my way. But as time wore on I began to realize that there was a point to which I liked competition. Past that point, my success and enjoyment suffered. I just found it unpleasant.

My insight around the corrosiveness of the competitive instinct is thanks also to officiating squash at the highest levels. The truth is stark: people are not their best selves when the competitive juices are flowing like a raging current instead of a steady stream. I have seen too many professional athletes come completely unhinged when their desire to win spirals out of control.

And it’s not just the pros. Last December, I happened to be officiating at one of the bigger junior tournaments, a vital stepping stone for players hoping to ascend to the collegiate and professional ranks. It’s a setting for all kinds of intensity, pressure, competitiveness, poor sportsmanship, rampant hunger for victory, gamesmanship, illegal tactics and general bad behaviour.

And that’s just the parents.

One moment stands out. A 12-year-old girl was on the verge of winning a match in the consolation quarterfinal, which meant it wasn’t particularly important, since neither she nor her opponent could finish in the top 16. The girl in question had played well and was up 10-4 in the fifth game. She was serving and only needed one more point to win, but she hit her serve out. No big deal. She still had five match balls. But then she hit another shot out, her opponent hit a winner, then another. Suddenly, from 10-4 it was now 10-8 in less than a minute. She looked to her coach and parents, close to tears. Her opponent served and the young girl completely whiffed it. She turned around, stared at her coach and … stopped breathing.

She seemed on the verge of a panic attack. She walked toward the door, opened it, and was about to leave the court out of sheer emotional overload. I put my hands out. “No, no!” I said. “I know you’re struggling, but you have to stay on court. If you come off court, you could forfeit the match. Just try to finish!”

I think we were all holding our breath over what might happen next. She took a deep swallow and closed the door. She trudged over to wait for her opponent’s serve, at which point her opponent promptly hit it out! Unexpectedly, the panicky girl won 11-9 in the fifth game.

Everyone heaved a collective sigh of relief as both girls came off court. I went over to where the young girl was sitting with her coach and parents. “I’m sorry if that sounded harsh,” I said. “I didn’t want you to accidently forfeit the match. I’m sure it was hard to get back on that court — good for you that you managed it.”

A highly stressful situation for a young athlete had resulted in no major tears and perhaps some insight into “sticking with it.” Crisis averted.

Or so I thought. About 10 minutes later, the father of the young girl who had lost the match asked me if I had a moment. I expected him to offer some kind of observation on how stressful these moments can be for young athletes. Nope.

“Why didn’t you disqualify that girl?” he said sharply.

“What do you mean?” I said. “Who?”

“That girl my daughter was playing should have been disqualified! You were standing right there. My daughter should have been awarded that match.”

I stood dazed and confused. I told him I saw a young athlete about to have a panic attack, not someone trying to gain a competitive advantage, and that I advised her to remain on court to finish the match.

“She stepped out of the court,” he said rudely. “I have it on video.”

I happened to look over toward a row of chairs near the courts. His daughter was sitting with a friend giggling about something. If she was devastated, she was doing a good job of hiding it. I turned back to the father.

“I’m sorry you feel that way,” I said. “But that’s not how I saw it.” I turned and left.

I admit it made me wonder what it would be like to grow up in a house where competitiveness crosses over into anti-social behaviour. Winning must matter at some level, because we value the ability of athletes to perform when the pressure is high. But, on the other hand, that’s not real pressure. Real pressure is working in the human services, dealing with a person who is struggling and looking for a lifeline.

And yet we keep score. For what reason? It’s probably related to something I learned, for better or worse, decades ago in the basement of our tiny house in northwest Calgary: People like to win and it usually doesn’t matter what it’s about.

Luckily, I enjoy the company of my siblings today. Maybe it’s because we got all that competitiveness out of our systems early, I don’t know. But I know that I feel differently about competition now than I did then.

There are times when it feels good to win. But it’s damaging to want victory too much. Competitiveness is useful in small doses, but when it surges out of control, it’s more a drug than a vitamin. Maybe we’d all be better off if we focused more on genuine wins — connection, empathy, usefulness. Let that be our challenge. In fact, how about this? I bet I can be more empathetic than you!

Oh, OK, wait …

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.