On a recent work trip, I met a fellow I just didn’t take to right away — let’s call him Mike. My gut instinct led me to draw some initial judgments. He was loud, a bit overbearing, given to unsolicited proclamations and, well, sweaty. I felt confident in my swift conclusion that Mike was not my kind of person. Then a funny thing happened on the way to my infallibility.

Before expanding on that, however, let me start at the beginning to deconstruct the origins of the problem. I hold my parents directly responsible. “For what?” you might ask.

To which I reply, “Does it matter?” I figure most everything good or bad about me is their fault or to their credit. Once you stamp a nickel at the mint, you can’t turn it into a quarter.

I was raised by a thoughtful and caring mother and father. Honest to a fault. Generous. Kind. They were great parents, which is almost certainly where most of the problems started. They instilled in me the belief that I, too, had the potential to become a person of sound judgment and acceptable moral character. I have lived a life that (the occasional parenting-of-teens outburst aside) is at least not an embarrassment to their example.

That’s the first issue at hand. The second is that — as a writer — I have had to interview, observe and interpret the behaviour of thousands of people. This has put me in the position of trying to figure out who is and isn’t full of it. I’ve met enough people in my life to have built an extensive mental database of human characteristics. I’m not Sherlock Holmes, but this line of work allows you to figure out things about people’s motivations, dissimulations, self-deceptions and the difference between genuine and performative actions.

Here’s my point: Being raised by honest and insightful people and having a career that involves talking to all kinds of folks deeply has made me able to size people up, landing in the vicinity of an accurate judgment of character. Let’s just say it out loud: I’m never wrong.

Or so I thought. It turns out, I was wrong about never being wrong.

Over the last few years, I’ve come to realize that those decades of being forced to read people has jaded me. Made me a hair too skeptical, judgmental even. Maybe I put too much stock in my ability to size someone up. I like people, mostly. But it’s fair to say that years of navigating the schemes, agendas and talking points of interview subjects has made me suspicious.

So, what showed me my hubris? This particular work trip wasn’t something I was looking forward to. Although outwardly it all sounded pleasant — nice resort, good food, a bit of golf — it involved having to socialize with strangers. I would offer more details, but you’ll soon see why I can’t. There were half a dozen other people involved in this trip, from parts of Canada and the U.S. And Mike was one of them.

It was hot where we were and, being a heavy man, Mike was feeling it. We finished a game of golf one day and, in the locker room, he informed me that he needed a minute to “get himself together,” whereupon he stripped nearly to his birthday suit in a semi-public area, wiped himself down in a highly graphic manner and pulled a whole new outfit from his backpack to change into. It was harrowing. “I sweat a ton, Curtis,” he said, as I waited. “It’s not pretty. The heat just does me in.”

Over lunch with the group, he offered opinions on just about everything and wasn’t shy about making himself heard. He was opinionated, loud and dishevelled. In my self-assurance, I immediately judged him as self-absorbed.

But over the course of the next couple of days, I began to observe small gestures from Mike — the way he held doors open for people, the way he remembered names, the way he wove what someone had just said to him into what he said next. Over one meal, he asked me what my wife did, which was a bonus point for him, but then a day later, when Cathy came up again in conversation, he remembered her name. At meals, he didn’t pick up a fork until everyone else’s meal had arrived. Playing golf one day, he picked up a couple of my clubs, which I’d left on the side of the green — a polite gesture on its own. But he held them by the shaft rather than the grip. I thanked him and, a couple holes later, he did the same thing for someone else, holding the clubs by the shaft. I asked him why he did it that way.

“COVID,” he said. “I just think people appreciate the gesture, but might not want a stranger putting his hands all over their grips.”

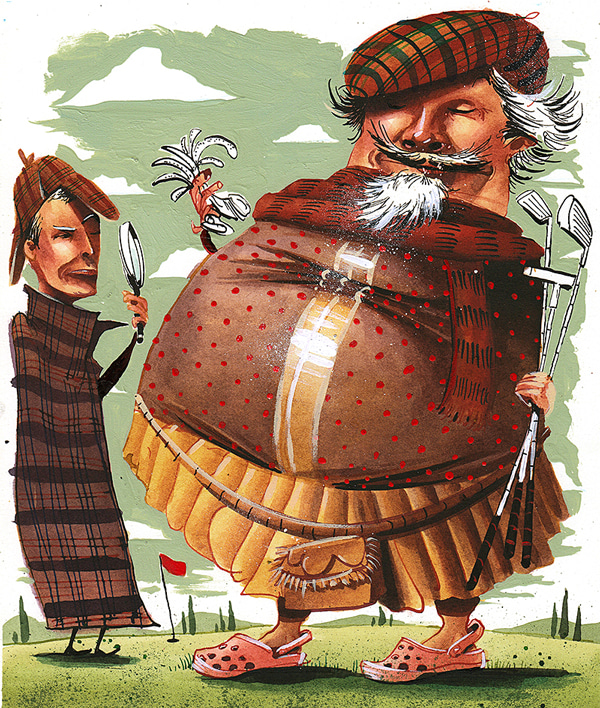

This displayed a level of pinpoint consideration you don’t often see. As we got to know one another a bit better, his mannerisms began to seem endearing. He’d hit a ball that appeared to be coming up short and instead of saying, “Hurry up!” he’d say, “Come on Grandma!” But it wasn’t just his humour. Some of his gestures were almost courtly, and I began to view him as more medieval monk than modern man. There was something Shakespearean, Falstaffian, about him.

When the week ended, I was sorry to see us part ways. If I’d only had my first impression to go on, I’d have retained a negative conclusion about him. It took some time, but I saw I’d made a snap judgment, and that maybe he was just a big personality. I never said anything to him about my early assessments, but I felt chastened.

Believe me, I am not going to suddenly change course and cease making snap judgments about people. Sometimes a moment is all the time you’ve got, and you have to size things up in a heartbeat. It’s good to cultivate that intuition, in case you find yourself in a situation where you need to make a decision based on minimal evidence.

But getting to know Mike a bit made me think that I ought to soften up. As luck would have it, I had another even more recent opportunity to test-drive my newfound open-mindedness and beatific tolerance. On a trip abroad I came across a very nice couple from Long Island, N.Y. We hit it off until the man started speaking confidently about his wild and deeply held conspiracy theories.

OK, obviously you can’t expect the serene acceptance of another’s reality to just take root all at once.

Perhaps at some level it comes down to your basic take on humanity. If you think most people are essentially good at some level and worth investing in, then you’ll take the time and let their qualities emerge. But if, like me, you feel that most people are, like me, flawed, inconsistent and not as fascinating as they think they are, I wouldn’t fault you for moving along.

It comes down to staying open to the space between gut instinct and the confirmation of that instinct.

Cathy put a magnet on our fridge a few years ago that still makes me grin. It’s a drawing of a person with their head opened up like a soft-boiled egg and a caption that reads, “If you’re too open-minded, your brains will fall out.” Not a message to live by, but I take comfort in the sentiment: Don’t be afraid to evaluate and to have an opinion. But the integrity of your judgment requires admitting that sometimes your opinion may need revision. Sure, don’t be afraid to make a call. But don’t be too proud to change it if the facts say otherwise. On that, at least, I am certain Mike would agree that I am not wrong.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.