A Class Act

Sarah Kent - 3 August 2023

Graduating law students marked a major milestone this year when they walked across the stage at the Jubilee Auditorium. The Class of 2023 is the 100th graduating class of the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Law since the school started offering a full-time degree.

The Faculty has a storied history of more than 110 years leading to its current reputation as a top Canadian law school. In addition to being the first professional Faculty at the U of A, it was also the first law program in Western Canada.

“The class composites hung on the top floor of the Law Centre show what more than a century can do,” says Raj Oberoi, ’23 JD. “The composition of the student body has changed. The number of students has changed. There are graduating classes from some of the past century’s toughest times.”

When the Faculty was established in 1912, it offered lectures on behalf of the Law Society of Alberta as well as courses for a part-time LLB program. Back then, a law degree wasn’t a requirement to sit the bar exam. Instead, aspiring lawyers took part-time courses while completing three to five years of apprenticeship.

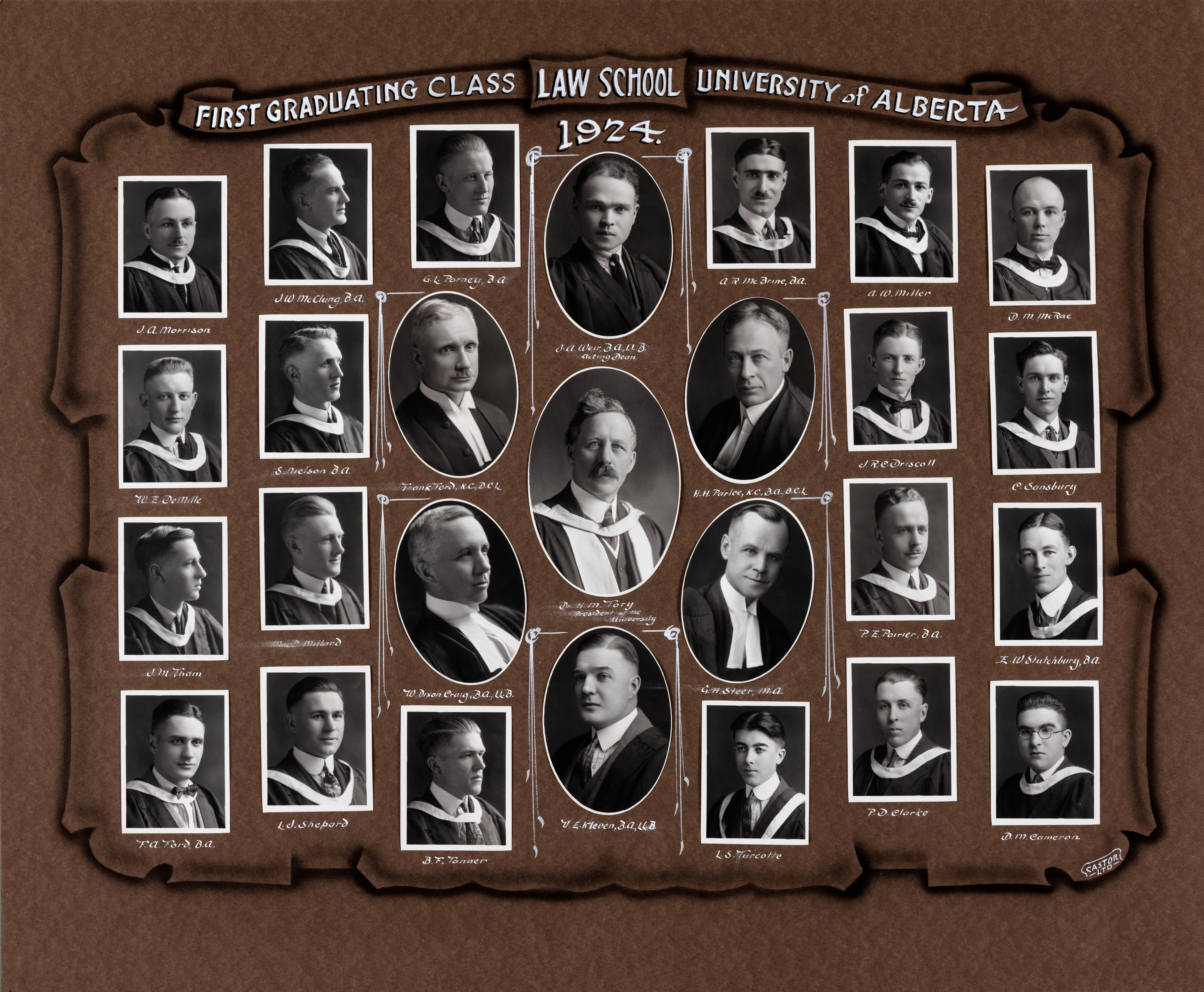

It was not until 1921 that the Faculty moved to the Harvard model of legal education, offering a three-year, fulltime LLB. Since that first full-time class graduated in 1924, more than 9,700 students have completed their law degree at the U of A’s Faculty of Law.

The Class of 2023 is part of a legacy of excellence, innovation and social responsibility that is foundational to the Faculty. But the law school journey for this year’s graduating class looked vastly different than any that preceded it. For the first two years of their three-year program, they persevered through the challenges of remote learning and uncertainty brought on by the pandemic.

As this year’s graduating class joins the ranks of the Faculty’s alumni, we trace the history of the Faculty to recognize how far the law school has come since that first graduating class.

THE POWER OF A VISION

When the Faculty of Law was established in 1912, Canadian legal education was in its infancy. Law societies, rather than universities, controlled curriculum. The creation of the Faculty is largely a credit to Henry M. Tory, the first president of the U of A, who made arrangements with the Law Society of Alberta to co-ordinate the society’s lectures and examinations.

At the time, legal education was modelled on English traditions that emphasized the practical apprenticeship of lawyers. Lectures, conducted by the Faculty at Edmonton’s courthouse, supplemented articling with classes offered before or after the workday.

Soon after the Faculty was established, Tory began to fiercely lobby for the modern and rigorous Harvard model, which employed a fulltime academic program. Under this model, the Faculty would teach students how to think like lawyers and how to approach legal issues critically and analytically.

Soon after the Faculty was established, Tory began to fiercely lobby for the modern and rigorous Harvard model, which employed a fulltime academic program. Under this model, the Faculty would teach students how to think like lawyers and how to approach legal issues critically and analytically.

In 1921, Tory’s vision for the future of legal education prevailed. The new LLB degree became the primary basis for admission to the bar, and students holding the new LLB were required to article for only a year after completing their degree. With greater control over the curriculum, the Faculty of Law was redesigned as a full-time, three-year program. The U of A Faculty of Law was one of the leaders in adopting this approach; it would be decades later before the Harvard model was adopted in Ontario.

HOW IT STARTED, HOW IT’S GOING

In the fall of 1921, 20 first-year law students started the new LLB program with John A. Weir serving as the first full-time professor and later as the first dean. Law classes were held on campus in a single room on the second floor of what is now Convocation Hall. In addition to Weir, there were a handful of part-time instructors.

The size and composition of the student body at the Faculty of Law has dramatically changed since that first graduating class, which comprised just 13 students. The Class of 2023 consists of 175 students, with women outnumbering men. Twelve members of the class self-identify as Indigenous.

“It feels immensely rewarding to be a part of the 100th graduating class, not only as a woman, but as an Indigenous woman,” says Emily Szeryk, ’23 JD, who is Métis from Manitoba.

“It feels immensely rewarding to be a part of the 100th graduating class, not only as a woman, but as an Indigenous woman,” says Emily Szeryk, ’23 JD, who is Métis from Manitoba.

The Class of 1924’s legal education focused on traditional areas such as contracts, property law and criminal law. Around 20 courses were offered. With the switch to the Harvard model, moot courts became a mandatory part of the curriculum. The moots took place in the lounge in Athabasca Hall with Weir and other instructors serving as judges. In the December 1921 issue of the Gateway, law students proudly declared, “Our Moot Courts have come to stay.”

More than 100 years later, the curriculum has greatly expanded. The Faculty now offers around 150 courses, including 14 mandatory courses. Course offerings include traditional areas of law that were part of the original curriculum and revitalized and emerging fields such as Indigenous law and climate change law.

As those early law students predicted, moots did come to stay. The Eldon D. Foote Moot Courtroom, which is currently undergoing technology upgrades, is the home for the moot program in the Law Centre. In 2022-23, 74 students participated in 20 upperyear competitive moots at local, national and international levels.

“Engaging in mooting has been transformative, honing not only my legal research and writing abilities but also my ability to think quickly and effectively on my feet,” says Annie Redmond, ’23 JD. Redmond has a decorated career as a competitive mooter, earning first place in the 2021 Brimacombe Moot and was part of teams that won fourth place at the Gale 2022 Cup and third place at the 2023 Wilson Moot.

“One of the most invaluable aspects of the mooting program has been the opportunity to receive feedback from esteemed judges who preside over courts across the country,” says Redmond.

Emilio Filomeno, ’23 JD, also reaped the benefits of mooting. Alongside Jessica Gill, ’23 JD, he advanced to the international rounds of the Brown Mosten International Client Consultation Competition in 2022. “We secured first place at the international level, bringing home this title to Canada, which had not been done in almost 10 years,” he says.

STUDENT LIFE

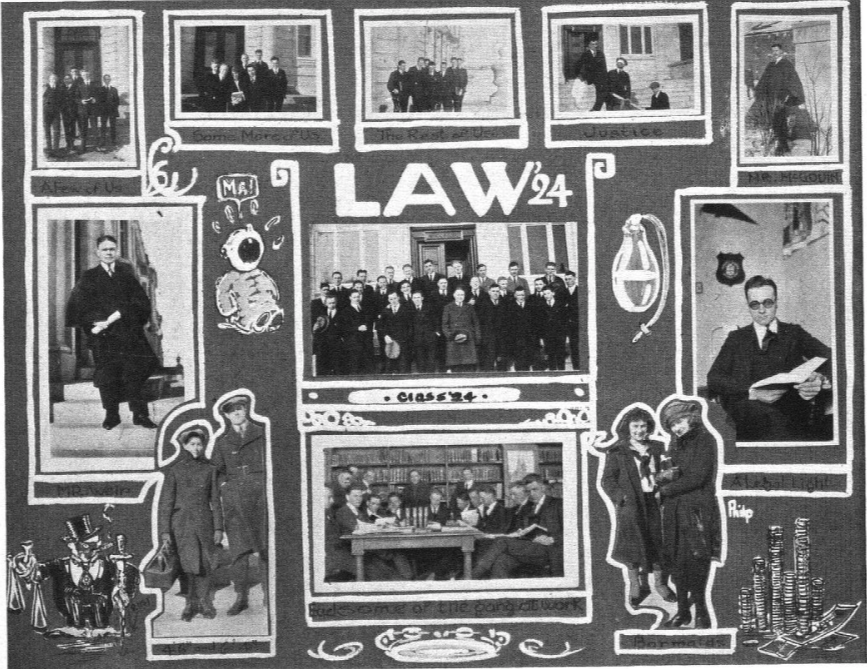

With law classes moving to campus in 1921, law students began to get involved with university life, joining student groups and intramural sports. Students in the 1923-24 Evergreen and Gold student yearbook reported, “In the affairs of the University at large, law students have taken a full part.” Law students were on the senior debating team, working on the Gateway and serving as executive members of the students’ council.

Law Club was established in 1921 with Sigvald Nielson, ’24 LLB, serving as its first president. The executive was made up of three students, and Weir acted as honorary president. The students hosted bi-weekly luncheons with guest speakers in downtown Edmonton. Law Club also began hosting the annual graduation banquet, a tradition that continues.

Today, the club has become the Law Students’ Association (LSA), with 15 executive members and a number of sub-committees. Filomeno served as the LSA president for the past academic year. “Being president was challenging at times but overwhelmingly rewarding,” says Filomeno, who prioritized kindness and compassion while representing nearly 550 law students.

In addition to the LSA, the Faculty of Law is now home to nearly 30 student groups.

Participating in intramural sports was a popular choice for the first graduating class. The students reported, “the Legalities succeeded in winning the interfaculty rugby championship” alongside students enrolled in commerce in 1924. Athletics continue to be a point of pride for the Faculty. Oberoi played for Law’s Golden Bearristers rugby team this year. Annually, law students face off against the alumni team.

“After the game, we all headed to a nearby restaurant, where I got to meet the group of bruised-up alumni,” says Oberoi. “Not only were they incredibly hospitable, but they also shared some valuable career advice that I won’t soon forget.”

Students have also carved out space for groups that promote diversity and inclusivity on campus and in the legal profession. For example, U of A’s chapter of the Federation of Asian Canadian Lawyers was established in 2020. Jessica Kim, ’23 JD, served as the FACL president for the past academic year. The group supports Asian law students with everything from mock interviews and mentorship programs to celebrations of Diwali and Lunar New Year.

“My hope is that all students feel included and welcome in law school and the legal profession,” she says.

PANDEMICS PROVIDE THE BACKDROP

When the Class of 1924 first began studies in 1921, the Spanish flu was still a recent memory. In 1918, classes at the university were cancelled as the virus spread. The years that followed saw intermittent outbreaks.

That is a familiar story for the Class of 2023, the first cohort to experience virtual orientation due to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The academic year that followed was a crash course in remote learning and socializing over Zoom.

“The Class of 2023 had a tremendous number of shortfalls and setbacks starting our first year in a global pandemic,” says Szeryk. “It was immensely difficult, and many of us were not confident that we would make it to the finish line. However, these difficult times allowed us to persevere and show up for ourselves.”

Kim echoes that positivity. “I believe that experiencing the pandemic while attending law school has made me a more resilient and optimistic person,” she says. “During difficult times, I experienced an increased sense of community, kindness and compassion for others.”

Kim echoes that positivity. “I believe that experiencing the pandemic while attending law school has made me a more resilient and optimistic person,” she says. “During difficult times, I experienced an increased sense of community, kindness and compassion for others.”

The Class of 2023’s final year saw a full return to in-person gatherings.

“For my 3L class, it was our first year not having to adjust to new pandemic measures,” says Filomeno. “This meant we could take advantage of all the in-person aspects of law school. Whether it was events, in-person classes, studying on campus, or seeing friends in the hallways — I cherished every moment of it.”

TYPEWRITERS TRADE FOR AI

When students of the Class of 1924 graduated, they entered a brave new world of legal practice that had been upended by technological advances only a couple decades earlier. At the turn of the century, law offices were transformed by the commercialization and accessibility of technology — from typewriters and duplicating machines to telephones and stenographs.

Today, the Class of 2023 is facing the triumphs and challenges of artificial intelligence revolutionizing the legal field. The Digital Law and Innovation Society, one of the Faculty’s newest student groups, has been on the cutting-edge of law and tech, says its president, Oberoi.

“With so much innovation still in its infancy, the club equips its members with the necessary tools to pursue their passions,” says Oberoi. As the legal field continues to be transformed by tech, Oberoi says DLIS is empowering its members to embrace the change and step out of their comfort zones.

A BRIGHT FUTURE

Members of the Class of 2023 are poised to continue making the Faculty of Law proud as they head into the legal profession.

Szeryk will be articling with Legal Aid Manitoba, working in the areas of family law and child protection. That focus was inspired by reconnecting with her Indigenous identity and observing her sister’s selfless career as a social worker. “I realized that through these areas of law, I will be able to help people, advocate for those who may not have the means to advocate for themselves. I’ll make a difference and give back to the Métis and Indigenous communities,” says Szeryk.

Kim will be articling at Pacific Medical Law in Vancouver, practising exclusively in the field of plaintiff medical malpractice. That path was inspired by her background in health services research, where she worked with vulnerable populations facing disproportionately poor health outcomes. “I increasingly recognized that the social issues we face today are the downstream effects of broader decisions in law and policy,” she says.

The Class of 2023 joins an elite group of alumni who walked the same halls. “There are many individual examples of graduates who have boldly tackled huge problems head on,” says Oberoi. “I hope the bicentennial class can look back over another hundred years of composites and think the same thing. Judging from the calibre of the people I have learned beside, I have little doubt this will be the case.”

For more history on the Faculty of Law, see Professor Emeritus John M. Law and Professor Roderick J. Wood’s article, “A History of the Law Faculty” in the Alberta Law Review.