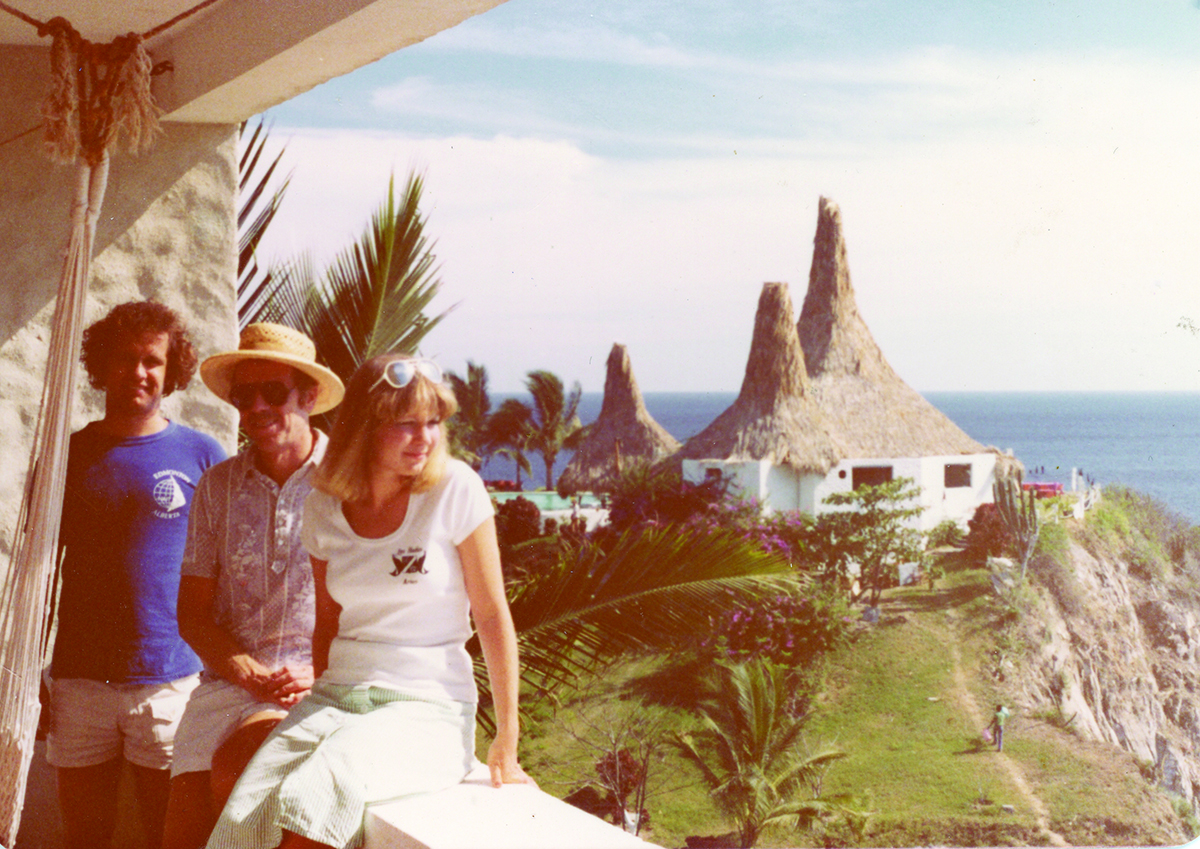

Gerry Youell was a man who loved life. His many friends were attracted to his fun-loving and easygoing company. He was a lover of good food and music - and wine, as long as it was what he called "good value."

"Dad was a great person to share time with," says Gerry's daughter, Lorea Chilton. "He was a lover of his relaxation time with his friends and family." He was disciplined, thoughtful and unassuming in life and work.

"Because of this discipline, he was a very successful petroleum engineer," she says. "He was an excellent and respectful communicator and a man of integrity - a true gentleman."

Gerry studied petroleum engineering at the University of Oklahoma (as the U of A did not offer a path toward Petroleum Engineering at that time) and spent his career at the Edmonton-headquartered Chieftain family of companies.

"He liked to be second-in-command," says Gerry's widow, Linda. "He was happy to let others lead."

Yet Gerry showed true leadership when he chose to earmark a gift in his estate for basic research. The goal of basic research is to improve our understanding of how nature and people work. Gerry, a friend of the University of Alberta, recognized that basic research is truly a good value, with the potential to generate applied solutions for many years. After he died, his gift went to the study of the herpes simplex virus.

The herpes virus is ubiquitous. It takes up residence within nerve cells and mostly just chills out there. It can reactivate, and when it does, it expresses itself at the end of the nerve - any place that particular nerve ends. An unlucky few, like Gerry, suffer more frequent and more intense outbreaks.

"Gerry was plagued by cold sores," says Linda. Anything could trigger an outbreak: heat, wind, sunshine.

"Every time he came back from a trip, and he travelled a lot for work and pleasure, he would have blisters," says his son, Gregory.

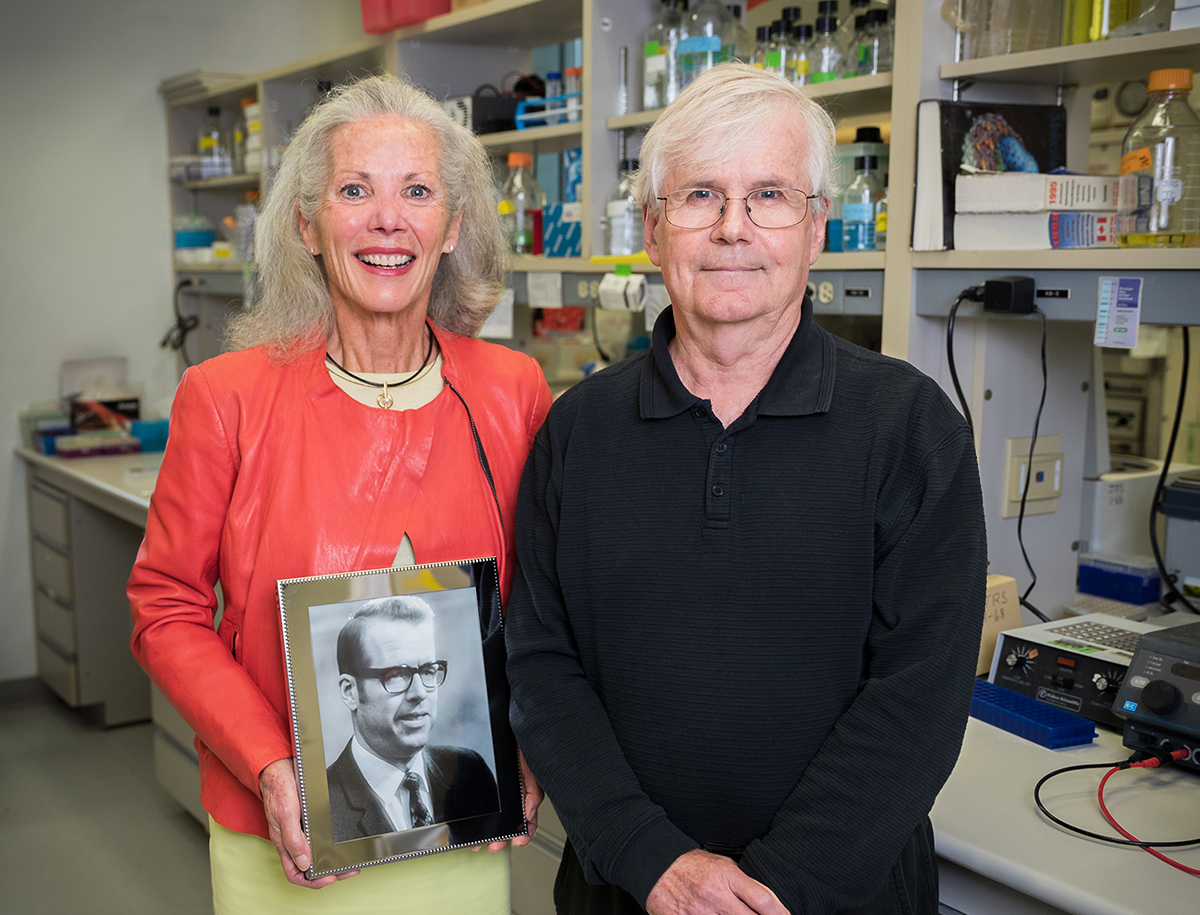

Gerry learned that Jim Smiley, Canada Research Chair in Molecular Virology and a virology professor at the University of Alberta, researches herpes viruses. He also learned that public support for basic research like Smiley's is falling in Canada.

Fortunately for Smiley, Gerry had an abiding sense of the value of such research and an understanding that basic research is the foundation atop which innovation and practical applications can happen.

For most of us, herpes simplex viruses, or HSVs, are an annoyance, causing cold sores or sexually transmitted diseases. Both can be fairly well controlled in healthy people. But, throw in, say, cancer treatments and the problems become more pronounced.

One HSV relative, cytomegalovirus, has few or no symptoms in adults but can be passed to the fetus during pregnancy, Smiley says. "It's the single most common cause of birth defects."

Plus, he says, viruses are unpredictable. Sometimes they can reactivate in the brain rather than on the lip, with devastating consequences. Any major insights into HSVs could offer understanding into how other viruses, such as chickenpox, rabies or influenza, work.

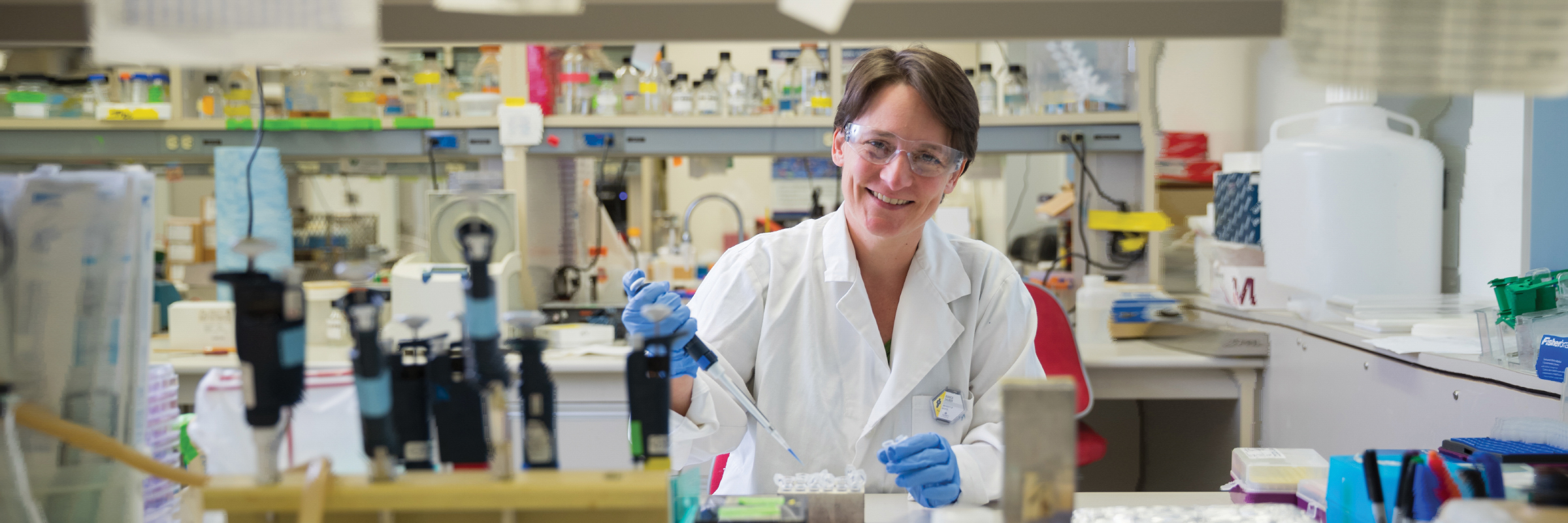

Gerry's gift allowed Smiley to fund a researcher, Bianca Dauber, who originally came to the U of A from the Robert Koch Institute in Berlin, for two years.

"She brings insight, experience, technical skills and imagination," says Smiley. "She has pushed forward research."

After Gerry died, Linda worked with the U of A to find the best way to use Gerry's gift. She toured Smiley's lab and heard about his work.

"It was serendipity, really," says Linda. "Before Gerry died, we happened to read an article about cold sore research at the U of A."

Smiley's lab appealed to Gerry as a great place to support, and his children, Lorea and Greg, ensured it happened. The family and the researchers, together, hope that one day, Gerry's gift will lead to effective treatments and even prevention.