In Chinese culture, the dragon (long) is a mythical shapeshifter whose most common form is a composite of various animals. As a revered protector that remains obscured from human sight, the legend of the dragon is rooted in the sound and rain of thunderstorms and other weather events.

Using select objects from the Mactaggart Art Collection, the Echoes of Thunder: Unveiling the Mythical Chinese Dragon exhibition aims to illustrate the origin of the Chinese dragon and follow its evolution from an imperial symbol to a widespread design motif through the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Note: images of this exhibition may appear dark, which is due to the low light levels used by curatorial staff to mitigate damage to the textile objects.

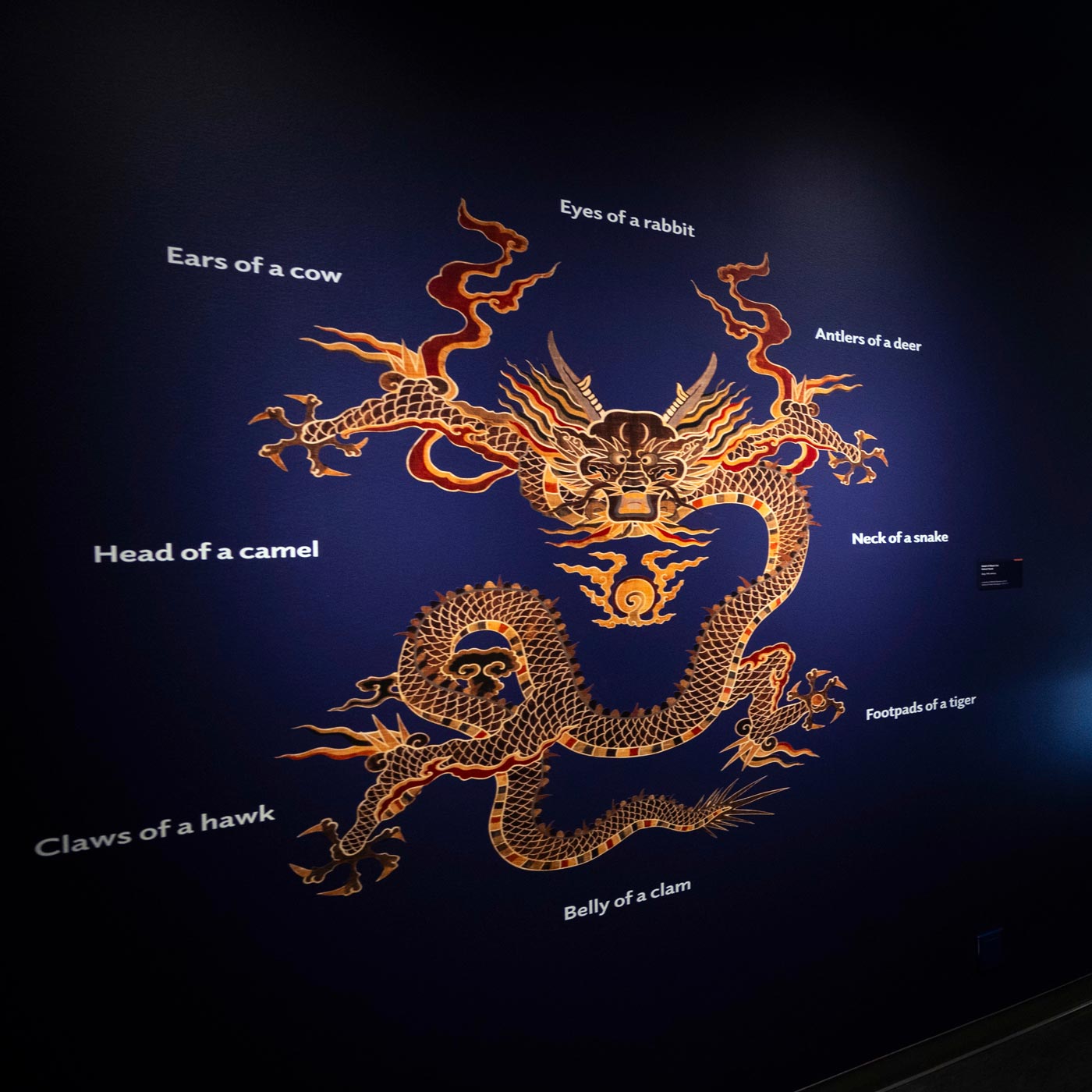

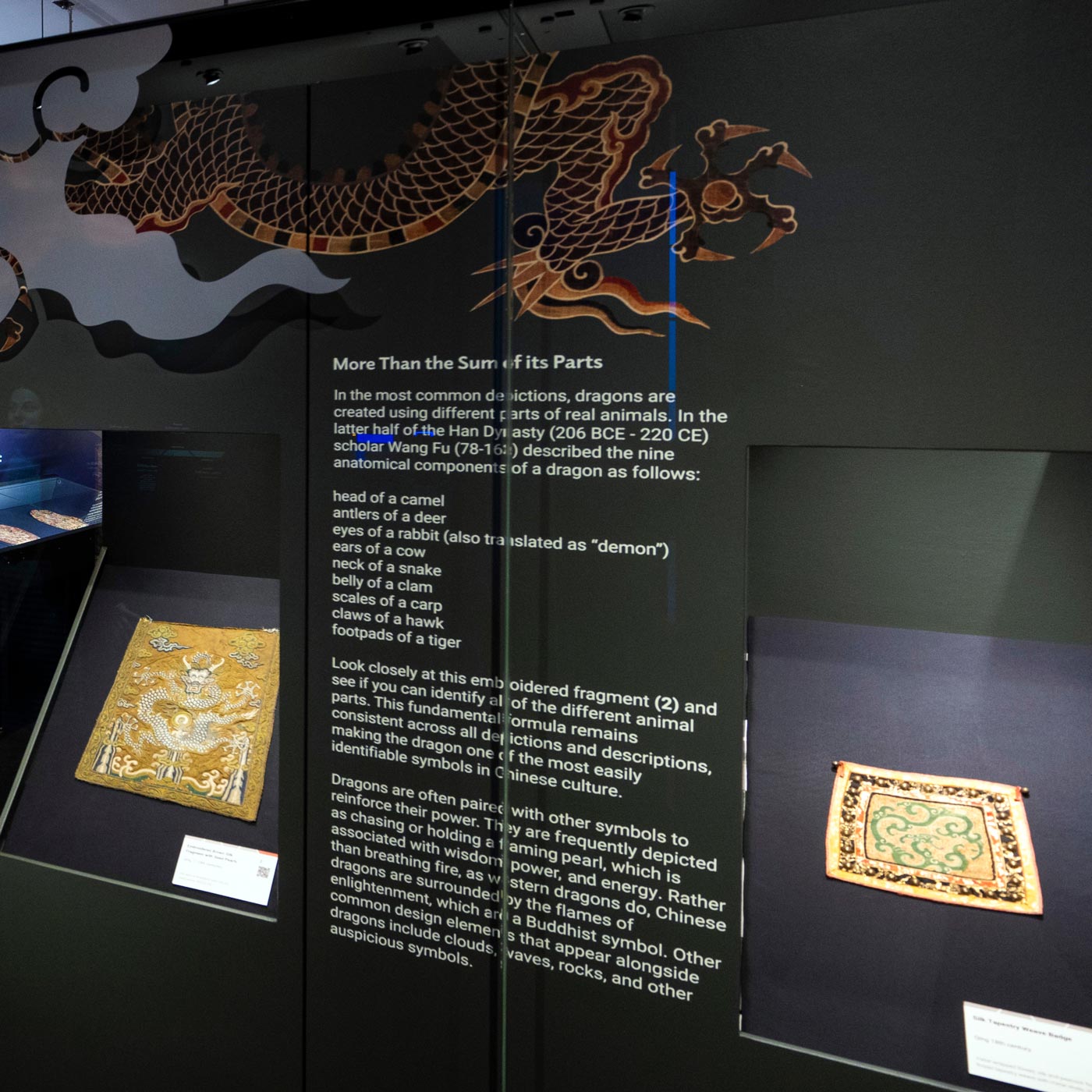

What does the dragon look like?

In the most common depictions, Chinese dragons (long) are created using different parts of real animals. In the latter half of the Han Dynasty (206 BCE - 220 CE) scholar Wang Fu (78-163) described the nine anatomical components of a dragon as follows: head of a camel, antlers of a deer, eyes of a rabbit (also translated as “demon”), ears of a cow, neck of a snake, belly of a clam, scales of a carp, claws of a hawk and footpads of a tiger.

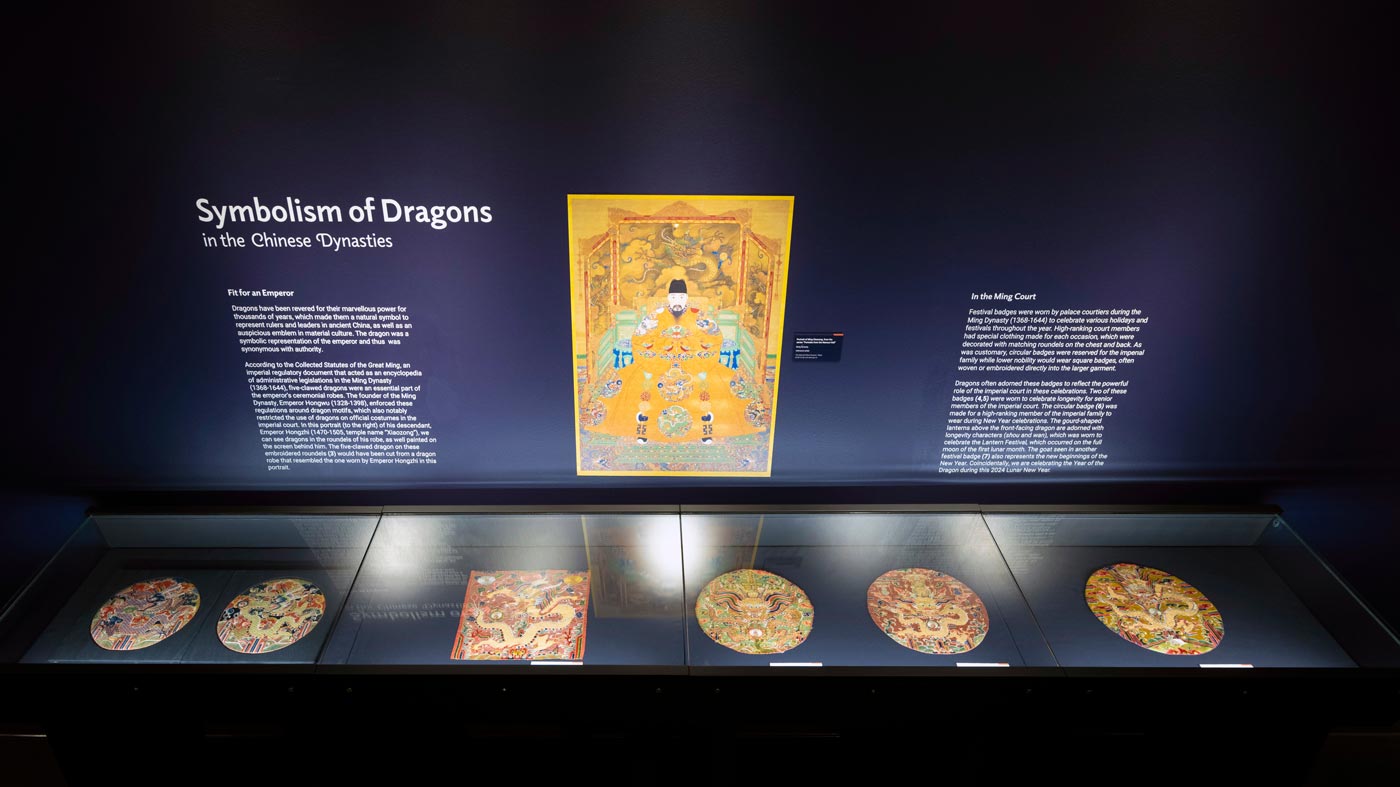

Fit for an emperor

Dragons have been revered for their marvelous power for thousands of years, which made them a natural symbol to represent rulers and leaders in ancient China. Palace courtiers wore festival badges during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) to celebrate various holidays and festivals throughout the year. High-ranking court members had special clothing made for each occasion, which was decorated with matching roundels on the chest and back. Dragons often adorned these badges to reflect the powerful role of the imperial court in these celebrations.

Changing shape

Imperial textiles were instilled with meaning from the combinations of motifs that symbolized the rank and virtue of the wearer. Observers would recognize the social status of imperial court members based on the colour, composition and decoration of their attire.

Dragons with five claws were worn by the emperor and his direct relatives. Civilians and lower-ranking courtiers still coveted dragon designs and used variations of dragon designs when decorating material culture to avoid violating regulations. The qilin was one such design, which resembled a dragon with hooves instead of claws.

Anthropomorphic figures

Anthropomorphism is the attribution of human characteristics to something non-human, such as an animal, object or mythical being. As design motifs, dragons are sometimes anthropomorphized in their depictions to be seen as more human-like or to reinforce virtues or lessons.

Teaching through dragons

Groups of dragons speak to the harmonious organization of a leader presiding over his subordinates, which corresponds to Confucianism and symbolizes social order. This tapestry hanging features a typical imperial composition of numerous dragons floating in the sky, surrounded by clouds, with rocks and waves below.

Be sure to visit this immersive exhibition, which is being held Gallery A in the Telus International Centre (11104 87 Avenue), during its run from February 24 - June 22, 2024 (Thursday, Friday and Saturday 12 p.m. to 5 p.m.). Closed Easter weekend.