At 8 p.m. on October 16, H.H. Gaetz answered his phone. He listened as the voice on the other end of the line revealed that the university would be closing. It was 1918 and that voice belonged to W.A.R. Kerr, then the acting president of the University of Alberta. A deadly strain of influenza was spreading across the world and had already arrived in Calgary.

This virulent form of the flu, commonly known as the “Spanish Flu,” was particularly deadly to the young and healthy. Soon all of Edmonton’s schools, churches, theatres, and cinemas would also be closed down to prevent large gatherings of people from spreading the illness.

Despite having cancelled all classes, the university remained abuzz with activity. An extraordinary number of people from the university and the local community volunteered to help care for the sick. For a month, Pembina Hall was transformed from cozy student residence and comfortable classrooms to emergency influenza hospital. More than 300 patients would find their way to the temporary hospital, including two teenage sisters from Westlock, Alberta.

16-year-old Miss Eileen Bala and her 17-year-old sister Mrs. Irene Yadlowsky worked in one of Edmonton’s packing plants. Catching the flu in November, the two young women would have heard the stories flooding in from across the globe; they would have experienced the order which required all Albertans to wear masks on public transit and seen their church cancel services. Knowing how quickly and deadly the flu would have been terrifying for the pair.

It was U of A faculty and staff, their family members, students, and members of the surrounding community who would help provide comfort and care for Eileen, Irene, and their fellow patients. Warm meals were expertly prepared by the University’s new household economics teacher, Mabel Patrick; nutritious and well-made meals were also sent out across the city to help families who were nursing the sick at home. This effort was aided by mathematics professor Ernest Sheldon and classics professor W.H. Alexander who helped recruit volunteers and coordinate the use of automobiles to transport nurses and food around the city.

The wives and children of faculty members helped to sew linens for Pembina’s makeshift hospital; linens were a critical resource in need of perpetual replacement. The constant ringing of the telephone, which in 1918 would have sounded like a persistent loud bell, was tamed by librarian Jessie Montgomery.

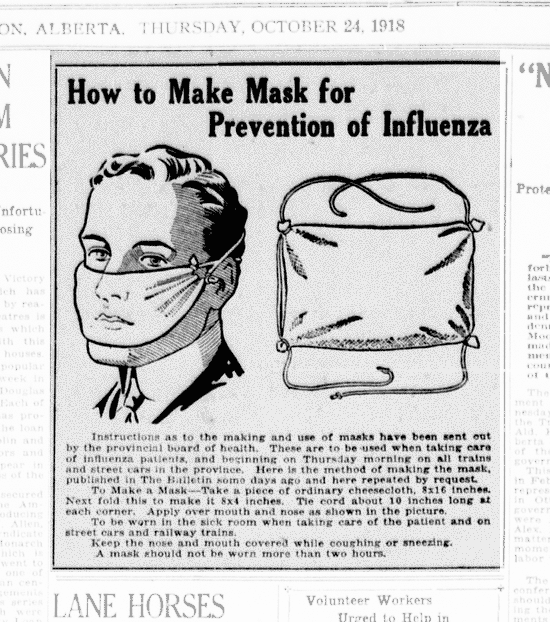

Assisting the ill, like Eileen and Irene, these volunteers put themselves at serious risk. The flu was highly contagious and apart from the controversial use of homemade masks of the day, there were no effective protections from it.

The epidemic had created a severe shortage of trained nurses, and so many untrained women volunteered to nurse the sick under the supervision of the few professional nurses who dedicated their efforts to those battling the dangerous fevers, coughs, exhaustion and possible pneumonia caused by the flu. E.K. Burgess, a University librarian whose brother was Pembina Hall’s architect, and Olive Ottewell, whose husband directed the University extension department, were among those who volunteered to do the dangerous work of nursing the sick.

When nurses could not be found, members of the University’s domestic staff, including Athabasca Hall’s janitor, James Collins, and Lena Miller, the senior housemaid, cared for sick students. Serving as orderlies was a task taken on by the university’s medical students, who worked alongside the tireless professors Muir Edwards and Gordon.

Despite everyone’s best efforts to protect the sick, casualties were a sad and constant reality, for both the patients and those who would ultimately sacrifice themselves in the service of them. William Muir Edwards was counted among the 72 patients who passed away in Pembina Hall. Etta Lockerbie’s role in the outbreak began when she nursed flu patients in their homes. She joined the workers at the emergency hospital on the day it opened bringing her much appreciated experience. Overworked and exhausted, she developed the flu herself after just one day of nursing in Pembina Hall and died of the Spanish Flu on November 5, 1918.

For Eileen and Irene, their time in Pembina Hall would come to an end too. Passing away at the young ages of 16 and 17, the sisters were unable to overcome the deadly influenza virus. Although the epidemic did subside, classes returned, and the last patients in Pembina Hall moved out, the Spanish Flu’s influence on the U of A community carried on. It was not the first, nor would it be the last time the U of A community would band together to “uplift the whole people.”

Suzanna Wagner — MA student, Faculty of Arts

Suzanna Wagner is a history MA student at the University of Alberta’s department of History and Classics, studying Canadian military nursing in the First World War. She has a broad interest in the histories of health, nursing, and material culture.