A few years ago, I had the great pleasure of being at dinner with former Montreal Canadiens goalie Ken Dryden (and Daniel Weinstock and Karl Moore, if I remember, but since even they will agree that they are slightly less cool than Ken Dryden, I am sure they’ll understand if I put them in brackets). I took the opportunity to ask about a mystery that has puzzled me for years: How did the playoff beard originate, and how did it spread to become generalized in hockey and beyond?

It is now normal for National Hockey League players not to shave during the Stanley Cup Playoffs, but this was not always the case. A quantitative study of the origin and evolution of the playoff beard could make a significant contribution to the study of cultural evolutionary phenomena. There was a time when there was no such thing as a playoff beard, and now it is a widespread cultural phenomenon. How does this happen?

While Dryden said he didn’t quite know where the beard came from, he offered up a potentially very significant insight. He said that before the late 1960s, with the playoffs consisting of only two rounds, played over two weeks, most players would not have had time to grow in a beard during their playoff run. This didn’t shed light on the origin of the phenomenon, but it pointed to a change in environment (from two rounds to three in 1968, and then to four in 1970) which might have created the conditions that allowed the trait to spread and become fixed in the population.

A quick look at the current Vegas-Washington series shows that the playoff beard has become generalized in hockey, and even baseball and basketball fans are now familiar with it. But how does a cultural phenomenon originate and spread?

The playoff beard Wikipedia page (did you need to ask if there was one?), speculates that it originated with the 1980 Stanley Cup winning New York Islanders, who had a couple of Swedish players, who possibly emulated their compatriot and tennis Champion Bjorn Borg’s superstition of not shaving during important tournaments.

Despite its tremendous potential for elucidating the mechanisms of cultural evolution, there is remarkably little actual scholarship on the origin and evolution of the playoff beard. Most of the sources tend to be journalistic or biographical. I am not aware of any prior quantitative treatment of the question.

If Dryden is right, we should not see playoff beards before 1968 (three rounds), and perhaps not even before 1970 (four rounds). If the playoff beard wiki page is right, we should see a sudden change in playoff beard frequency starting in 1980, the first of the Islander’s four consecutive conquests. In fact, perhaps this playoff beard question captured my unconscious imagination early on, as in the 1970s and early 80s, I was a secret Mike Bossy/Islanders fan, which as a Montrealer, I could never have admitted publically without risking a serious school yard beating. Until now. See? I feel better already.

Methods

I searched the Getty Images website using the search string Stanley Cup finals and focused on images taken from 1965 to 2010. I identified photos of players taken during the Stanley Cup playoffs final series. For each photo, I recorded the team, the year, the number of players of one team visible, and the number of beards visible. Some pictures generated two records if players from both teams could be seen and their beard status clearly ascertained.

See for yourself

I originally tried using the traditional posed team photos with the Cup, but quickly realized that many of these, especially before the 1990s, were taken at some undetermined time after the game, rather than immediately after. Additionally, many of the team photos were also clearly photos taken at some unknown time during the season, with an image of the Cup (sometimes clumsily) superimposed in front of the players. Even the more recent (now traditional) pictures of the team with the cup, on the ice, right after the game, are somewhat chaotic and it is difficult to count the players and the beards. The on-ice, in-game pictures have so far proven to be the most reliable source of data. They also proved to be more difficult to find, especially for the years before the 1990s.

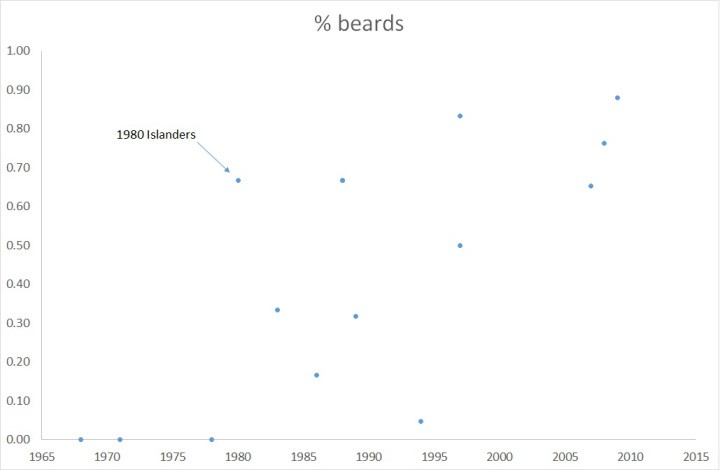

For the graph, I used only pictures on which 5 or more players of one team could be seen, with their beard status clearly visible. This helps the percentages actually make sense. I had about three hours to do this, scattered over a week, so don’t expect too much for now.

Results

As figure 1 clearly shows, playoff beards are essentially absent before 1980. They suddenly increase in frequency with the 1980 Islanders. They become dominant by about 2000 and have remained so since.

Discussion and Future Work

The results lend support to Dryden’s contention that the playoff beard could not have happened before 1968. They also bring considerable support to the idea that the beard originated with the 1980 Islanders. From there it seems to have spread fairly quickly over two decades, to become almost standard by 2000.

There are several interesting possibilities for future research. First, a more systematic survey of the photographic evidence is required. I hope to do that in time for next year’s Stanley Cup final. I might even spend some time this summer in a (gasp!) library, looking through microfiche newspaper archives. My very quick and spotty examination shows a clear pattern, but more resolution is clearly needed.

I am aware that my current study only looks at the number of beards present during the Stanley Cup Final series, which is not necessarily the number of playoff beards present. To identify playoff beards more accurately, I will have to look at in-game, on-ice pictures taken at other times of the year, and compare with picture taken during the finals.

Control data is also needed. Does the frequency of beards in the playoffs mirror the frequency of beards in the general population (initially at least)? In media advertisements? One method to evaluate this would be to look at street scenes and news reports from a given year, and compare these with playoff beard frequency and frequency of beards in ads in Sports Illustrated, for example. If any grad student would like to take this on as a thesis project, I am happy to supervise. I might even have a bit of funding for it.

Second, was the playoff beard a trait that already existed in some form before the addition of playoff rounds, but was only fully expressed after the change to a longer playoff format? Did it originate more than once but only become fixed once the environment favoured its spread? It is extremely interesting to note, for example, that in the 1968 final series between Montreal and St. Louis, BOTH goalies, but not the other players, show very clear stubble, but not a full beard on the in-game, on-ice pictures. This is at the very end of the period when it is possible to see the beard status of hockey goalies in on-ice photos, and also happens to be the very first year of the three round playoffs. However, if the playoff beard had its origin among goalies and if Montreal was somehow had something to do with it, I would expect Ken Dryden would have been aware and would have said something. Or maybe not. Who knows?

Another intriguing data point is a picture of Montreal scoring ace Guy Lafleur, taken in the locker room after their 1971 (edit: 1972) conquest of the cup, applying after-shave, as if he has just shaved (perhaps ritually?), right after the game, suggesting a potential playoff beard.

It would also be interesting to investigate how the playoff beard spread, whatever its origin. The fact that it seems to be associated with the 1980 Islanders suggests that we might be looking at prestige biased transmission, but testing that hypothesis will be challenging. Still, I look forward to it.

Originally published on ArcheoThoughts on May 29, 2018.ArcheoThoughts on May 29, 2018.

André Costopolous — Vice-Provost and Dean of Students

André Costopoulos, PhD, joined the University of Alberta as Vice Provost and Dean of Students in July, 2016. Born and raised in Montreal, Costopoulos holds a BA (Hons) in anthropology from McGill, an MSc in anthropology from the Université de Montréal and a PhD in archeology from the University of Oulu, Finland. He began his career in 1999 as a visiting assistant professor in the Department of Sociology, Anthropology and Social Work at Eastern Connecticut State University. In 2001, he joined McGill as a research associate and sessional instructor in the Department of Anthropology and joined the faculty as an assistant professor in 2003. From 2012–2016, he served as McGill’s Dean of Students.