Escaping the surly bonds of earth takes so much money and energy that some denizens of the International Space Station drink recycled urine to limit the water that needs to be hauled up. The cost of sending astronaut Kjell Lindgren's bagpipes to the ISS, for example, has been estimated at $259,000. (Science can't explain why we'd do this.)

So why would AlbertaSat, the university's donor-funded, student-led aerospace club, traffic in disposable satellites? In 2017, the club's Ex-Alta 1 satellite became the first Alberta satellite to reach orbit.

Eighteen months later, and by design, it burned to a crisp as it re-entered Earth's atmosphere.

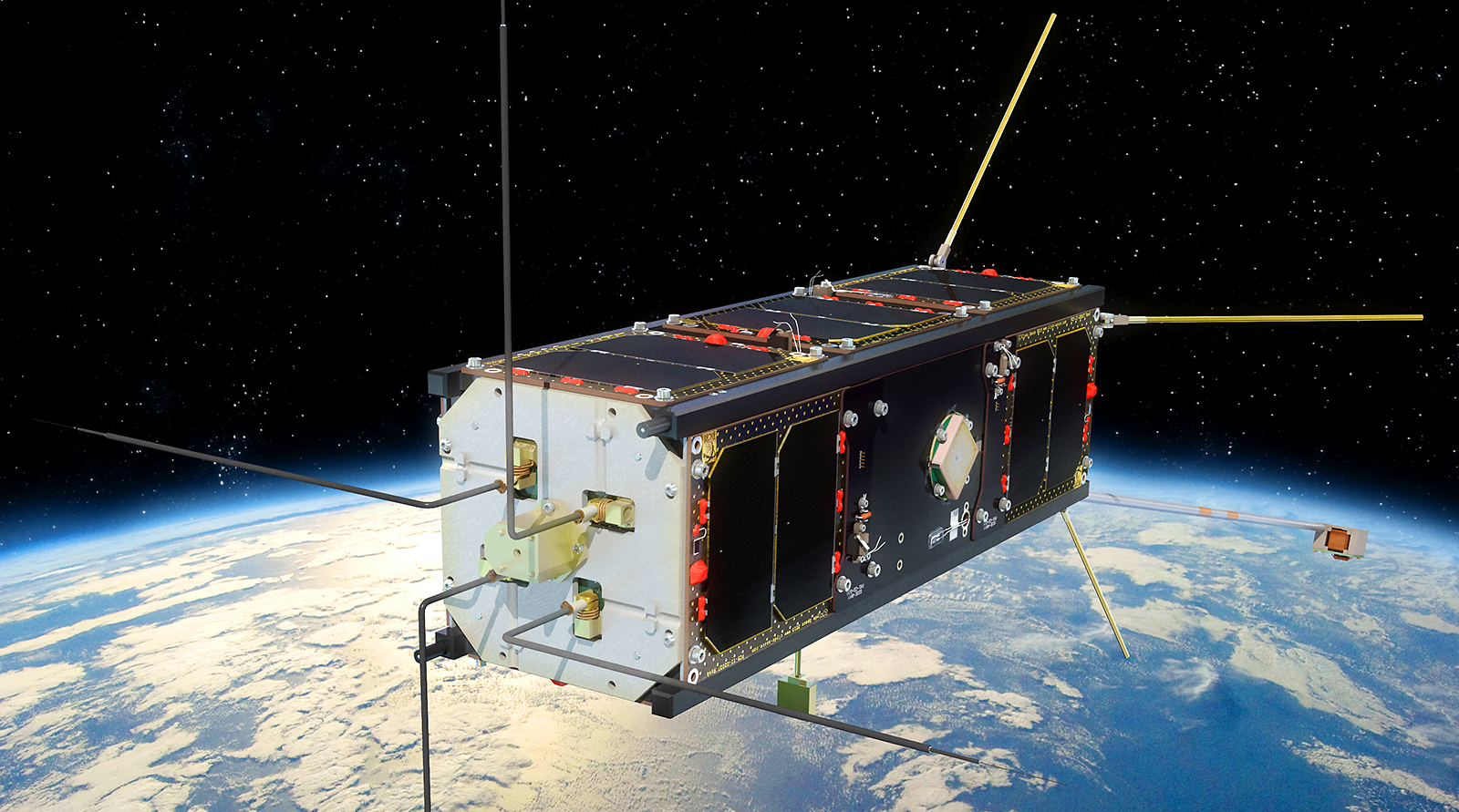

Certain kinds of space science are best done from low orbit, around 400 km above sea level. Objects orbiting at that height, like the International Space Station, periodically need a boost or they'll slow down and burn up entering the atmosphere. But no such boosts come for CubeSats, the loaf-sized satellites like this one designed and built by AlbertaSat. (Take a look inside.)

For its brief life, Ex-Alta 1 collected information about the Earth's magnetosphere, helping researchers understand space weather and potentially crippling geomagnetic storms. For such a small package (30 x 10 x 10 cm and just 2.64 kg) student-built satellite Ex-Alta 1 (shown here with a few bragging points) was such a success the group is at it again. Ex‑Alta 2, due for launch in 2021, will use multispectral photos to track wildfires. (It will also pioneer open-source CubeSat design practices.) Then it, too, will burn up in the atmosphere.

AlbertaSat team members don't feel too sad. "If you spend years doing something and it accomplishes a goal, it's a success," says engineering student Erik Halliwell, who leads the design of the power systems of Ex-Alta 2. "It doesn't matter how long it takes to accomplish those goals and then burn up."

Here are some things to know about the dearly departed Ex-Alta 1:

1: U of A's nanoFAB etched a tiny silicon chip with the names of all the donors whose contributions helped launch the satellite. The CubeSat (and the names) travelled around the world about 8,000 times before a scheduled plunge into the atmosphere.

2: No bigger than a loaf of bread, the satellite called Ex-Alta 1 packed such specialized equipment as a fluxgate magnetometer, a multi-needle Langmuir probe and a radiation dosimeter to monitor space weather.

3: The little spacecraft, which orbited at 415 km from Earth at an inclination of 51.6 degrees, had an onboard computer that stored telemetry and instrument data, transmitting it to student satellite operators at the U of A.

4: Ex-Alta 1 was part of a swarm of dozens of cube satellites, which together demonstrated that building viable spacecraft can be done quickly and cheaply, opening new doors for researchers and industry.

5: The satellite featured nine solar panels, each with two photovoltaic cells to generate power with a peak output of 1.23 W per cell. Four lithium ion cells in the battery pack stored that power, providing a reserve capacity of 38.5 Wh.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.