An international team of scientists including two neurobiologists from the University of Alberta is weighing in on the latest controversy over the brain power of Tyrannosaurus rex.

Dinosaurs have been extinct for more than 60 million years, but they can still cause a bit of a ruckus. It was as though an asteroid hit the world of dinosaur research in 2023 when prominent neuroscientist Suzana Herculano-Houzel of Vanderbilt University claimed that dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus rex were far more intelligent than had been believed.

In an article in the Journal of Comparative Neurology, she argued that T. rex had an exceptionally high number of neurons, the cells that carry and send information in the brain. In fact, Herculano-Houzel said there were so many neurons in the brain of a theropod such as T. rex that it may have been as smart as a baboon and capable of cultural transmission of knowledge and tool use.

It was a provocative study that was immediately greeted with skepticism in the scientific community. And now an international team of paleontologists, neuroanatomists and cognitive psychologists has come up with a new study, published in the journal The Anatomical Record, that refutes Herculano-Houzel’s claims.

Cristian Gutierrez-Ibanez, a research associate in the University of Alberta’s Department of Biological Sciences, was one of the leaders of this new study debunking the notion that the T. rex was as smart as a baboon.

“There were a lot of people who thought the record needed to be set straight,” he says. “Particularly because it did make it into the press. You end up with this popular idea that T. rex was super smart and could use tools and have culture and you go, ‘Whoa!’”

An academic firestorm

Herculano-Houzel had touched off an academic firestorm, and lots of scientists wanted to respond. Gutierrez-Ibanez says a group of scientists eventually decided to combine their efforts and author a single paper to refute her findings. “We said there is no point in eight different things being written to say this is wrong. Why don’t we just put them all together?”

It was a project unlike anything he had been a part of, with academics from a range of disciplines working together. Doug Wylie, a professor in the U of A’s Department of Biological Sciences, says a project like that can be a challenge, with a lot of cooks in the kitchen. But thankfully, a couple of people took control of the process. Wylie credits Gutierrez-Ibanez for being one of them, particularly in the analysis of data.

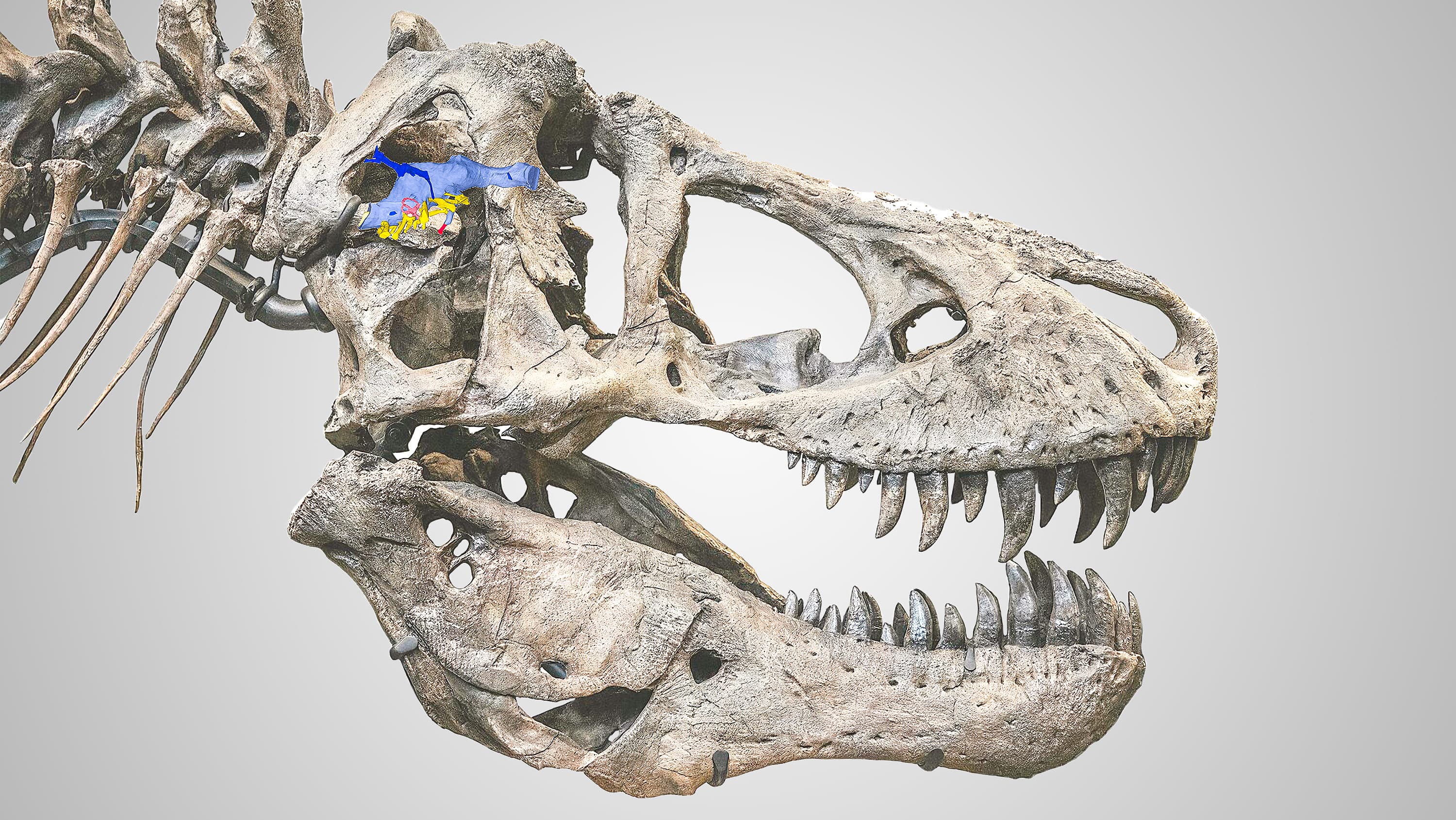

The team examined the techniques that Herculano-Houzel used to estimate dinosaurs’ brain size and number of neurons in their brains, and found that her assumptions were unreliable. Despite the temptation to think of them as big birds, dinosaurs were reptiles, and reptile brains are far different from those of mammals and birds. For one thing, they don’t fill up the skull cavity. There is a lot of cerebrospinal fluid taking up space as well. “The first time I dissected an alligator brain, I took the top of the skull off and I went, ‘Where is the brain?’” says Wylie. “Because there is this big space in there.”

Then there is the animal size factor. An adult male baboon can range from 14 to 40 kilograms. A T. rex could be in the neighbourhood of seven tons. According to Gutierrez-Ibanez, the number of neurons scales with the body size. “We don’t know why it’s true, but it is true. A larger animal needs more neurons.” That means T. rex needed a lot of neurons for just doing the basics with such a large body, with none left over for using tools and transmitting cultural knowledge.

Reptile brains are also packed more loosely with neurons than the brains of mammals and birds. “She’s focused on the neuron number, and they are too high anyway,” Wylie says of Herculano-Houzel’s study.

And reptiles don’t have the same kinds of connections and circuits in their brains that mammals and birds have. Gutierrez-Ibanez says that would limit the complexity of their social behaviours.

So, T. rex was probably only about as smart as a crocodile, not a baboon, the team concludes. That was likely a very good thing for the animals being hunted by T. rex. But it doesn’t mean the theropod didn’t have a decent reptile brain. After all, they were also able to dominate the world for millions of years, which is no mean feat.

We are not dissing T. rex,” Gutierrez-Ibanez says. “We are just saying that claiming T. rex had the intelligence of a baboon and culture might be taking it too far.”

Gutierrez-Ibanez and Wylie’s contribution to the paper was funded by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada.