Update Four: Writing with the James Bay Cree: Naming Perpetrators Dr. Ruth DyckFehderau

Dr. Ruth DyckFehderau - 1 July 2024

As an Adjunct Professor in the Department of English and Film Studies, I write nonfiction books with the James Bay Cree of Northern Québec. Currently we’re working on a book series of Indian Residential School (IRS) recovery stories. My Cree supervisors hire outsiders for trauma stories because “our own [Cree writers] have enough to carry.”

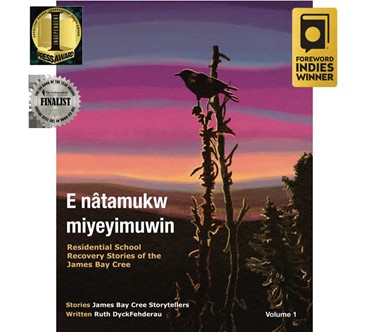

Previous posts about this project are here, here. and here. More information about our most recent book, E nâtamukw miyeyimuwin: Residential School Recovery Stories of the James Bay Cree, Volume 1, including purchase details, here.

In this posting – required for my adjunct appointment and approved by Cree Board of Health and Social Services of James Bay (CBHSSJB) who publish, own, and control the books – I’ll discuss the delicate matter of naming perpetrators, and about two ongoing lists.

Each year, twice a year, I travel to the remote, lush James Bay Cree territory of Eeyou Istchee and visit approximately three (of nine) communities.

Shoreline, Cree Nation of Eastmain, Eeyou Istchee

Oujé-Bougoumou Cree Nation, Eeyou Istchee

I work with local Elders and Community Support workers to identify and prepare appropriate psychological supports for storytellers, and to spread the word about this project in the community. And then, folks who want their IRS-related stories (including intergenerational stories) published in a book contact me and we begin the long process of story-gathering, story-drafting, story-checking, and editing, going through the steps repeatedly until the storytellers are satisfied. Usually, along the way, storytellers share many more details than the final version presents. To prevent later abuse of those details, all earlier drafts, notes, and recordings are destroyed. In the end, only the single approved version remains.

E nâtamukw miyeyimuwin: Residential School Recovery Stories of the James

Bay Cree, Volume 1

In the earliest days of gathering stories for E nâtamukw miyeyimuwin, my supervisor and I sought confirmation from lawyers that we could publish the names of perpetrators without repercussion. Many storytellers had spoken of experiencing, witnessing, and recovering from torture or abuse. Often the abuses were more severe than the Canadian public knew. Often they were devastating in their ordinariness, in the ways in which abuse was normalized, as commonplace and expected as sunset. And often, the storytellers named those who had abused them. Indeed, as Judith Herman writes, in a book I regularly consult, Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence – from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror (1997), the act of describing the trauma and naming the abuser is not easy to do. Reaching that point can take years of psychological labour – but it can return a sense of power to the victim. Wanting to support the survivors and storytellers, in early story drafts, I included the actual names of abusers who had visited extraordinary cruelties upon children and made them ordinary. We hoped the lawyers would agree with the practice.

Unfortunately, the potential repercussions the lawyers foresaw were legion. Perpetrators’ children sometimes shared given and surnames with their parents and naming perpetrators could lead to mistaken identities. Others who were in no way related to perpetrators might share surnames with them, be affected by the publicity, and sue for defamation. Poor IRS recordkeeping sometimes led to several spellings of a surname and the wrong spelling could lead to a mix-up and to potential legal battles. And so on. Even though the storytellers often had evidence that would hold up in court and were not likely to lose any lawsuit, the simple fact that they could be sued at all added a level of risk that the publisher (Cree Board of Health and Social Services) deemed not worthwhile. I returned to my early story drafts and changed the perpetrators’ names.

What then to do? How could we honour the formidable work and healing survivors had done to reach a point where perpetrators could be named? We still don’t have the answer to this question. But, as I gather the stories, I keep a list of names – priests and nuns, counsellors and supervisors, teachers and cleaning staff – who abused and tortured the Indian Residential School students of the James Bay Cree, in the hope that one day I am able to publicize it in some way.

I keep another running list as well, perhaps the most gruesome list I have ever made: A list of what happened to the babies. While the intense calorie restriction kept many girls amenorrheic and thus unable to become pregnant or carry a fetus to term, other girls became pregnant by their rapists and birthed the children. This list, like the perpetrator list, we’ve been advised not to publish, at least for now. But I keep it nonetheless, in the hope that one day a venue where these names, these histories, can be known and identified in such a way as to reveal this part of history while also keeping the victims safe.