Teach less, more deeply; students need time to process and embody what they learn. If we give students too much information to process, they will only have time to learn it superficially. We need to teach less so that students have the necessary time to deeply process what they are learning.

I began thinking differently about teaching for breadth vs depth a decade ago when I noticed that students I had taught in prerequisite courses were somewhat unprepared for the subsequent advanced course. Maybe this says something more about my ability to teach, but on the other hand, the student learning outcomes from those prerequisite courses suggested that learning had happened.

To better facilitate student learning I transitioned my courses to Team-Based Learning (TBL). My aim in implementing TBL was to enable students to practice applying their knowledge to problems while in class. But to make room/time in class for students to practice applying their learning meant that I had to teach less stuff. I needed to give students more cognitive space so that they would have the opportunity to more deeply process what they were learning. This is what Jeanette Norden advocated when she gave the keynote address at this year’s Festival of Teaching and Learning.

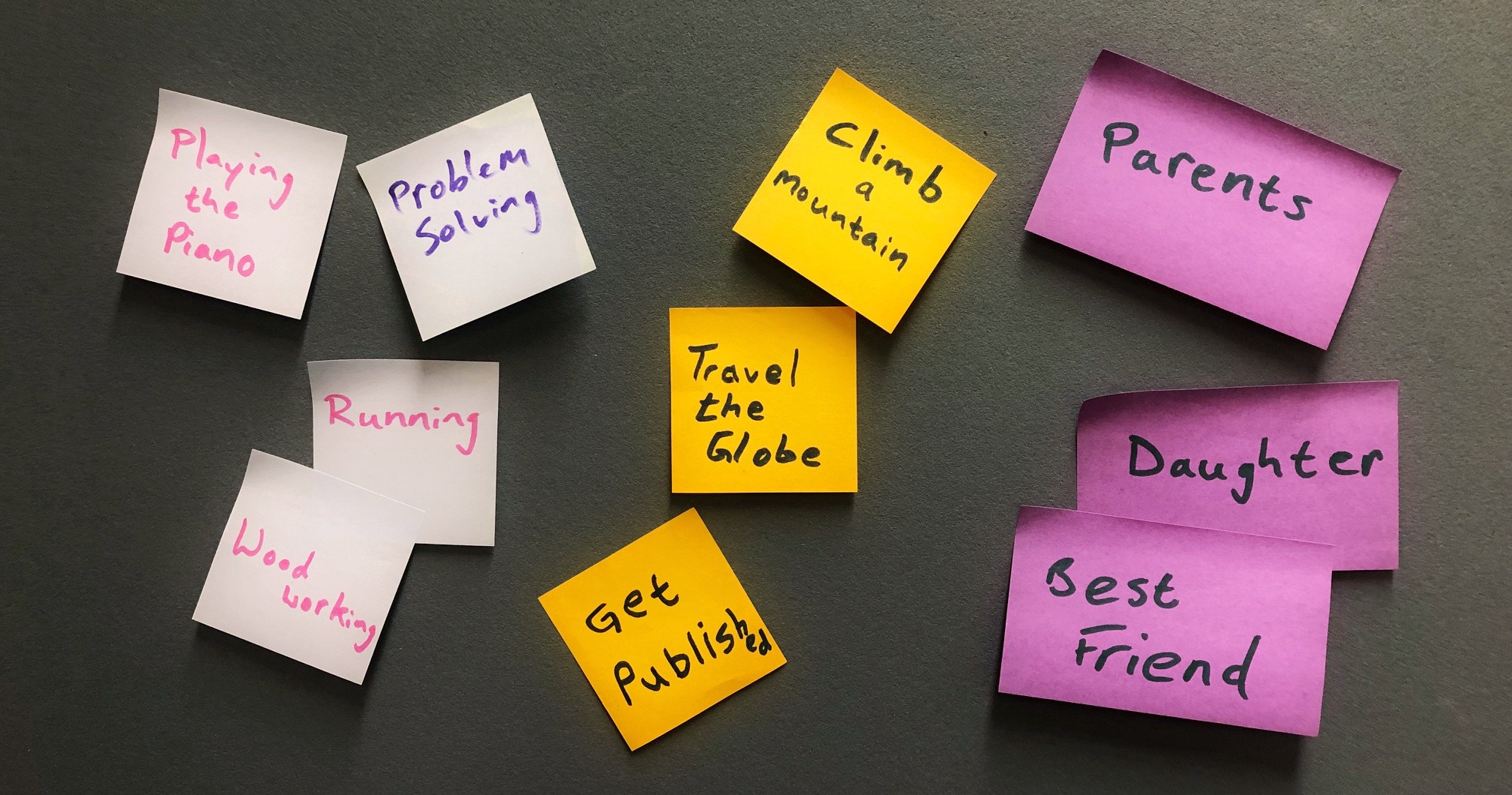

For her, it’s important to teach her students about neurobiology, but it is just as (if not more) paramount for them to learn that they are dealing with real people that are often in a crisis situation. One of the ways she does this is by having students write on three different cards their love, their dream, and their talent.

Then she walks around the room and randomly take one of the cards away from students stating that they have just lost it due to some medical issue. They could have lost a partner, or their ability to speak or move. Any of these would be life-altering and impact what they love, their dream, or unabashed talent. She does this to help students make the connection that this is what their patients will experience when they, as medical doctors, give life-altering news to their patients.

What it got me thinking about was how do I translate her approach to my biochemistry and molecular cell biology courses? In medical school, it is particularly relevant that what they are learning theoretically, academically about disease and pathology directly impacts how they need to relate to people and care for them. This is learning made manifest. But how do I do that when I am teaching something that is basic science in a class where the vast majority of students will not be health professionals?

I think what Jeanette was trying to emphasize is that while we teach our subject we need to model to students how to be a human being that treats everyone with care, empathy and respect. It does not have to be in a health or service discipline. We need to teach students to develop their intellect and thinking ability while also enabling their personal development.

This is difficult when the course material we are teaching is not directly tied to everyday circumstances or at least not in the realm of lived experience. For example, in the courses I teach, as much as cellular chemiosmosis is a part of our everyday living, it is not something that necessarily affects how we interact with each other.

So, what is the solution? How do we apply what Jeanette modelled for us so that we can teach our students so that they are not simply thinking, disembodied from the human experience?

I think it is in how we teach. Something that I have been thinking about for some time is that it is not just what we teach but how we teach that is so fundamentally important to developing the whole student. Thus, we need to consider the teaching strategies we use in our classroom — are they isolating or are they social/communal? When we interact with our students, do we display care and empathy to their lived reality?

Some people disagree with me about this. Some are of the opinion that university is all about the head and that university professors should be solely focused on developing the intellect. I think that is our primary purpose, but we cannot do that in a vacuum ignoring the fact that our students are human beings. We need to respond to our students as human beings. It is akin to applying the golden rule in our teaching — do unto others as you would have them do unto you: when we teach, we need to interact with our students as humans similar to how we wish others to interact with us.

As teachers, we need to be willing to join our students in the messiness of learning. Doing so is one of the ways that we can create that cognitive space that I mentioned earlier.

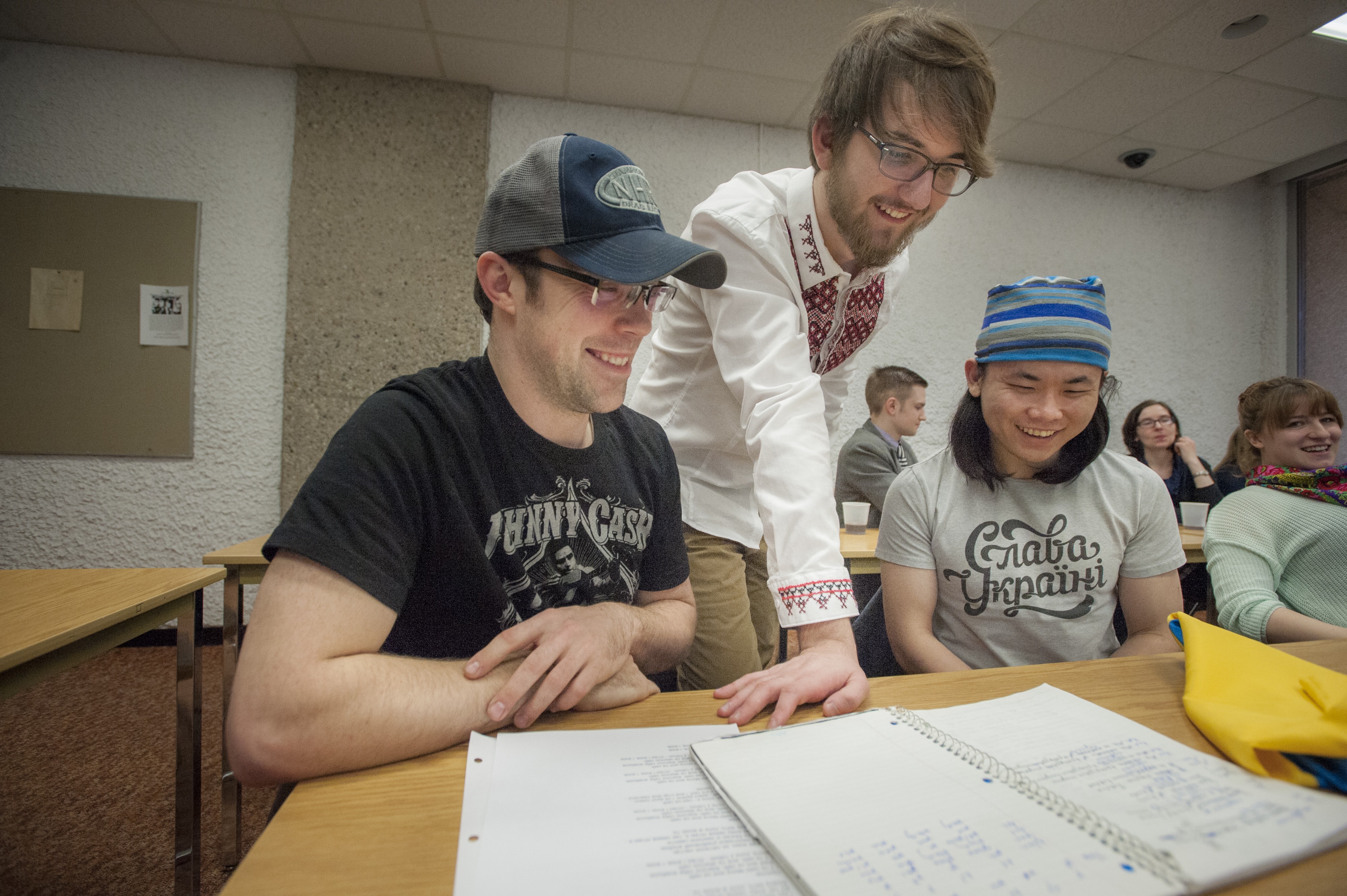

For example, by walking around the room you can ask them questions like, how are you doing? Do you understand the problem I have set for you? Do you need more time to think about it? What is tripping you up about it? When doing this, it’s important to make sure that they know that it’s okay for them to admit that they’re struggling with an idea or a tool — and respond to them with an example of your challenges when you were a student. This provides them with that time they need to apply the lessons that they are learning, while simultaneously giving you an opportunity to demonstrate empathy. After all, teaching should be personal and relational.

In order for students to engage intellectually with the problems and context we set for them, they need to understand that it is ok for them to fail and that it is possible to succeed even after failing. I, as their professor, am an example of that. Intellect without empathy is a dangerous thing and university professors are in a good position to develop one in the context of the other.

Neil Haave — Associate Director (Scholarship of Teaching and Learning), Centre for Teaching and Learning

Neil Haave has been teaching molecular cell biology and biochemistry at the Augustana Campus since 1990 where he served as Chair of Science and Associate Dean. Neil is a recipient of a McCalla Professorship and Augustana’s Teaching Leadership Award and Teaching Faculty Award for the Support of Information Literacy. Neil is interested in developing scholarly approaches to teaching which includes researching our own educational practices in light of the published literature on teaching and learning in higher education. He occasionally posts to his blog, Actively Learning to Teach.