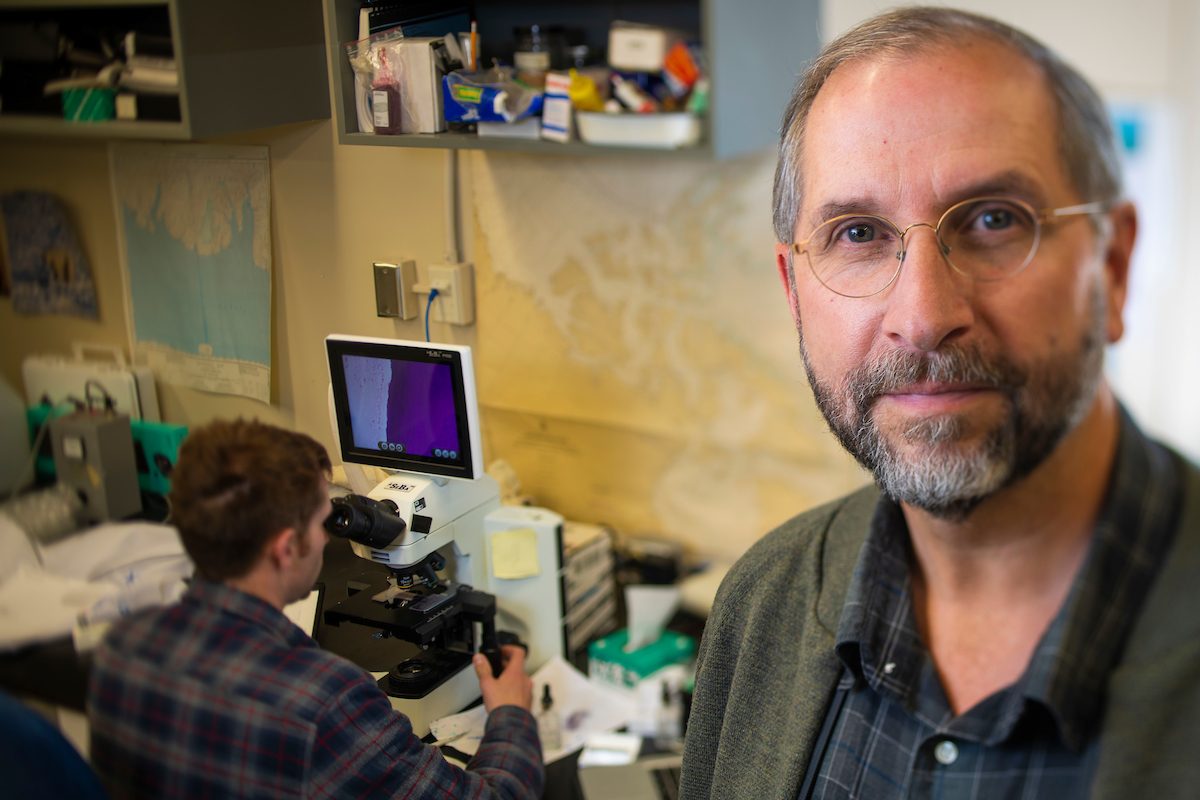

Andrew Derocher, professor in the Department of Biological Sciences, and our November Instructor of the Month. Photo credit: John Ulan

Blending course material and experience, Andrew Derocher in the Department of Biological Sciences is well-known for using "bear stories" to reinforce the concepts he teaches. And after 36 years studying polar bears, there's no shortage of ways to use the bears as a model species. Meet our November Instructor of the Month, and hear from Derocher on making the most of field research, taking advantage of unexpected opportunities, and the importance of washing the dishes.

What's your favourite course to teach?

My favourite course is Zoology 408 (Biology of Mammals). I view it as a capstone course for biology students, and I explore the evolution, anatomy, behaviour, and ecology of mammals to reinforce principles that students have learned in other courses. Mammals are so diverse that we can explore a huge range of topics.

I also have an iterative writing assignment where students write a research proposal and I work with them to develop their ideas and methods. Regardless of the trajectory the students take, someone will ask them to write a proposal, and it's a great experience to have done one as part of their coursework.

Why should people learn about this subject?

Being mammals ourselves, students can often relate their own experiences to wild species. I emphasize that point when I discuss the importance of various mammalian traits. Understanding other species may provide individuals insights into themselves.

I focus on the philosophy that any question in biology or ecology can be answered using the fundamental principles learned in science. I focus many lectures on energetics and explore how species have evolved to maximize their fitness. If doesn't matter if I use bats, whales, or badgers to explore a topic because it's the principles that I try to bring forward. I use mammals as a means of integrating information that students have learned through many of their other courses-that could be physics when we explore flight in bats, or organic chemistry when we explore hormone regulation.

What's the coolest thing about this field?

The diversity of mammals is outrageous, and the range of adaptations to hot, cold, deep diving, feeding, food deprivation, and numerous other traits are endlessly fascinating. There are so many incredibly interesting aspects of their ecology that I'm never short on a new insight from a fresh publication. From bats hibernating in snow drifts to polar bear mating ecology to diet selection in kangaroo rats, there's no end to what we explore.

What was your favourite learning experience as an undergrad? How do you incorporate that experience into teaching your students?

I was an undergrad at the University of British Columbia, and I was in awe of what some of my professors were studying. I was particularly drawn to those professors studying large mammals-but I was just as interested in birds, fish, lichen, plants, and anything else that was alive. I could have studied almost any taxonomic group, but I was drawn early on to carnivores.

I was most influenced by those few professors that were keen to interact with undergraduates and those one-on-one meetings influenced my teaching profoundly. I make time for undergraduates my top priority: I don't hold formal office hours as they often don't work for undergraduate schedules, and line ups for input don't help their time management. I make appointments one at a time, and it works. I believe that direct interaction with professors is an essential part of an undergraduate's education. Exploring ideas, research, graduate studies, and career options is important. I also use these opportunities to garner input on course content and assignments.

What was it that drew you to this field?

I grew up catching bees, fish fry, frogs, snakes, and investigating everything wild nearby. From there, books became a window on wildlife. Then, the more time I spent outdoors, the more interested I became in pursuing a career in wildlife. I'm an accidental professor, and I had intended on being a management biologist-but one opportunity led to another.

My career with bears started with grizzlies on the coast of British Columbia, and I was asked what I was going to do over winter when they hibernated, and I said I would look for a master's position. That led to the question "Have you ever thought about studying polar bears?" Not until that moment. I was soon on a path that has lasted more than 35 years. Polar bears are a great species for teaching. Students are as fascinated by them as I am, and our research examines not only the bears themselves but how they can be studied as a model organism to ask fundamental questions in ecology.

What do you feel is the most important piece of advice you give to your students?

Make the best of each and every opportunity presented to you, and good things will happen. The harder you work, the luckier you'll be. It's a competitive world, but following your passion will make it easier.

For field biologists: never get the cook mad at you; wash more dishes than anyone else, and you'll always be welcome in camp; if you're flying, keep your pilot happy; and when it comes to equipment, one to use, one to lose, and one as a spare. After over 60 expeditions to conduct field research and thousands of hours in aircraft, these rules have served me well.

What would people be surprised to know about you?

I have a passion for Inuit art and antique clocks. Inuit art is a bit more logical given my core research area, but clocks fascinate me with their precision and craftsmanship. I can do basic repairs-but ironically, finding the time to do so is challenging.