Eight years after the University of Alberta feted its first graduating class, The Trail was launched to unite alumni scattered “far and wide in Alberta” — and, as the editors soon learned, around the world.

Letters, accompanied by the obligatory two bucks for dues, arrived at The Trail with postmarks from Vancouver and Chicago, China and South America. The gossipy “Sparks from the Anvil” column detailed the European adventures of Rhodes Scholars alongside the LinkedIn-style job announcements of grads closer to home.

A little bit Facebook, a little bit phone book, the magazine’s mission was to connect alumni with their alma mater and with each other. Here are a handful of grads whom we’d love to have met who made an appearance in the magazine during its first decade.

1: Beatrice Georgina Parlby (Buckley), 1903-89

’25 BA, ’44 Dip(Ed), ’24-25 Pandas basketball

After graduating with a degree in agriculture, Beatrice Buckley (everyone called her Bea) returned home to Gleichen, Alta., where she was doing “anything and everything” to earn enough to attend a four-month teacher training program at one of Alberta’s “normal schools.” “My latest adventure,” she quips in a November 1925 letter to The Trail, “has been cooking for threshers to the tune of ‘Groans from the Crew.’”

What we know

Farming and politics went hand-in-hand in Buckley’s family. Her parents moved to southern Alberta from Ireland when she was about three. In 1921, she started her studies at the U of A just as her dad, John Charles Buckley, was beginning a 14-year career as the elected party whip for the United Farmers of Alberta. The UFA’s July upset of the governing Alberta Liberals also saw the election of Irene Parlby, who would become one of the Famous Five in 1929 and Buckley’s mother-in-law two years later. Like John and Irene, Buckley advocated for farm and rural life, serving for a time as president of the Alix, Alta., local of the United Farm Women of Alberta. She also followed through on her dream to become a teacher, a career she continued with great joy until her retirement in 1970. “She loved teaching,” her children Geoff, Gerry and Susan say on the Central Alberta Regional Museum Network’s website. “Her students, including her own children, were taught to explore, question, acquire knowledge and solve problems. They were encouraged to love and appreciate drama, art and music.”

What we love

Buckley made an endearing plea in the November 1925 issue that urged The Trail to follow through on a half-formed notion to start an “Alumni Reading List” for graduates. “Personally, I think the idea is a splendid one,” she writes, then sums up what most folks hesitate to say out loud. “Many of us … dread the possibility of dropping back into our haphazard, pre-varsity habits of reading — yet are very much puzzled as to just what books to select.” (Check out the modern-day answer to her plea: a virtual alumni book club.)

2: Margaret Hazelwood Brine (Gold), 1898-1985

’18 BA, ’24 MA

We meet Margaret Gold (illustrated above) at the Hotel Macdonald, where she’s serenading members of the Alumni Association with a solo performance of a children’s song written by Rudyard Kipling. “A most pleasing number,” sighed The Trail in February 1924. “Miss Gold has recently returned from studying abroad, and her singing was, as usual, much appreciated.”

What we know

In between her undergraduate degree and her master’s, Gold spent three years studying at the Sorbonne. “The glamour of study in Paris is rose-tinted and delightfully attractive.” But it wears thin in a hurry, she writes in a frank and funny Trail essay in November 1924. By then, she was already teaching classics at the U of A, which she did until her marriage to developer Charles Brine in June 1928 — a wedding the Edmonton Journal called a social event of “unusual interest.” Brine’s death in 1963 left her quite wealthy and she set about giving the fortune away. She became a generous benefactor to Edmonton arts institutions and created an annual scholarship for female students pursuing graduate or doctoral studies at her beloved alma mater.

What we love

Teacher, philanthropist, performer. A lover of good times. But she was also a trailblazing mountaineer, one of few women climbers at the time. Her alpine adventures included being part of the first group to ascend Simpson Ridge. She climbed Mount Assiniboine, nicknamed the “Matterhorn of the Rockies,” then headed to the Swiss Alps to climb. With her trusty Kodak, ingenuity and bits of string, she managed to sneak some selfies into her photo albums. But the story we’d love to hear her tell is the one about how, in July 1924, she was to have been the first woman to ascend Mount Robson, along with other members of the Alpine Club of Canada. The honour ended up going to renowned mountaineer Phyllis Munday because, so the story goes, Gold ended up partying with other Alpine Club members and gave up her spot. We’ll never know if that’s true.

3: John Thomas “J.T.” Jones, 1898-1986

’22 BA, ’26 MA

The front-page editor’s note in November 1923 wastes no time letting readers know that a new boss is in town. “The Trail,” it reads, “will henceforth endeavour to keep the graduates more in touch with affairs of the university.” So begins the era of J.T. Jones, who goes on to steer the magazine for five issues and remains on its editorial committee for many years.

What we know

Jones arrived in Edmonton from Wales in 1909. He graduated in 1921, became a U of A English instructor the following year and was appointed assistant professor in 1926. He spent his entire career at the U of A, teaching the poetry of John Milton. He became head of the English department and vociferously defended the arts faculty when he felt it was under threat. Jones was president of the Alumni Association from 1924 to 1926 and took great pride in his role of raising funds for the Convocation Hall pipe organ, which was installed on Nov. 11, 1925, in memory of the 82 staff and students who died in the First World War.

What we love

Under Jones’s guidance (and, we believe, his pen) The Trail went on a mission to cajole, guilt and otherwise motivate grads to “do your bit, no matter how small” and donate to a memorial fund to purchase the $12,000 pipe organ. “The University of Toronto has built a magnificent memorial tower; McGill has set up several graven tablets. We have done nothing,” despairs an unsigned editorial in July 1924, when Jones was editor. “If we have any self-respect, if we have any pride in our university, if our college spirit is anything more than an empty name, if we have any common gratitude for those who died for us, we can do nothing but give increasingly to this fund.” Later editorials cheered the contributions. “Graduates, wherever scattered, are showing that they are loyal to the U of A and that they feel the worth of the tradition left by eighty of their comrades who gave up their lives,” he wrote in The Trail in March 1925.

4: Daniel Roland Michener, 1900-91

’20 BA, ’67 LLD (Honorary)

“Has anyone heard from D.R. Michener?” writes The Trail in November 1923. “Rumour says that having returned from Oxford, he has settled down in godless Ontario. Drop a line, Roly.” Perhaps he wasn’t the best correspondent, but Roland Michener — “pride of Lacombe, Alta.”, “Roly” to his pals and eventually “His Excellency” to the rest of us — was clearly a beloved target for some good-natured teasing. “Cheer up girls!” notes another Trail entry, sharing the news about the Rhodes Scholar’s treks around Europe. “The last sentence of his letter … assures us that he is still a single man.”

What we know

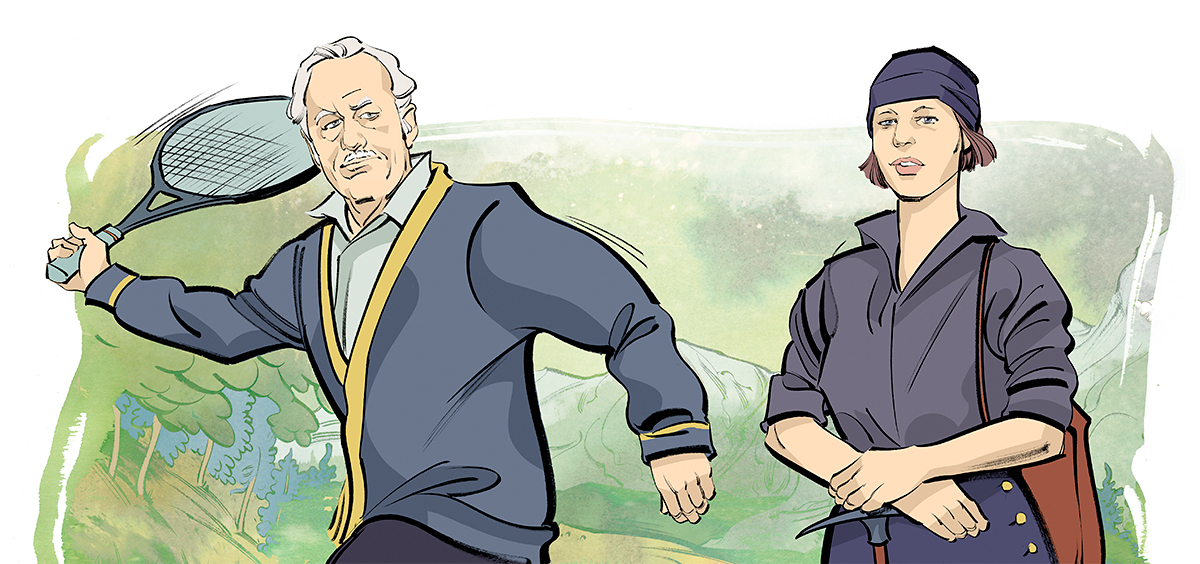

Michener (illustrated above) took time away from his studies in 1918 to join the Royal Air Force with three U of A chums. According to a campus newsletter, “a bevy of Edmonton’s youth and beauty” were on hand to bid farewell to “these four popular young bloods.” Michener’s valedictory address was almost prescient, speaking to a university’s function “to produce leaders and equip them with all the essentials of good citizenship.” He became all of these things: a lawyer, federal politician, Speaker of the House of Commons and, from 1967 to 1974, the Governor General of Canada.

As Canada’s head of state, he abolished the curtsy. “I shall be happier as a Canadian among Canadians with such customary Canadian salutations as the handshake or bow,” he said. In 1970, he was asked to sign the War Measures Act, a request he did with some hesitation — and while wearing his pyjamas, according to The Canadian Encyclopedia.

What we love

Michener is synonymous with Canada’s most important journalism awards and also established several awards related to sports, which were his true passion. While at Oxford, he played competitive hockey and ran track. He even played in the 1923 Canadian Tennis Open, partnered with a very good friend named Lester B. Pearson (they were eliminated in the first round). The so-called “Jogging GG” established a trophy for an Ontario AAA Juvenile hockey championship, the Michener Tuna Trophy for sport fishing and was ardent supporter of Canada’s ParticipAction program.

5: Margaret “Peg” Stobie (Roseborough), 1909-90

’30 BA

Peg Roseborough, an honours English student from Vermilion, Alta., threw herself into life on campus. She was a member of the French and arts clubs, writer for The Gateway and local theatre star who “attained striking success for extracurricular efforts” on stage, writes The Trail in 1930. That year, she also became the eighth U of A student to receive an Imperial Order Daughters of the Empire scholarship to the University of London.

What we know

After her year abroad, Roseborough returned to Canada and completed her master’s and PhD at the University of Toronto, where she met and married another English PhD student named William Stobie. The couple moved around the United States for about a decade, working at post-secondary institutions in Indiana, Missouri and New York, before returning to Winnipeg to teach in the University of Manitoba’s English department. The “quiet and humble” couple left $7 million in stocks, books, papers and Inuit art to the U of M for the purpose of purchasing new books for the university’s library.

What we love

Roseborough obviously loved a good story and we think she had a few to tell. For example, stories about the nepotism laws in 1950 that forced her — and faculty women on campuses throughout North America — to resign her U of M job because her husband was on staff. (After which she spent a few years acting and directing local theatre as well as working for the CBC in various dramatic roles.) Or perhaps the story of her high-profile resignation from Winnipeg’s United College in 1958, when she quit in outrage after a fellow instructor was fired when the college’s principal read a private letter the instructor had written. But we think the best stories from this Gateway veteran would detail the shoe-leather journalism behind her books about two Prairie characters — Frederick Philip Grove, a Canadian writer of gritty pioneer novels with a mysterious Prussian past, and Charles Bremner, a Métis farmer who fought for government compensation after his furs were stolen by the militia during the 1885 Northwest Rebellion.

6: William Frederick “Bill” Seyer, 1890-1972

’15 BA, ’18 MSc

“Dr. Bill Seyer gives little information of the work at U of B.C. except that they are at last getting the permanent building of that institution put up.” So reads The Trail in July 1924, four years after UBC hired Seyer as an assistant professor of chemistry. A later issue reports that he was among the first members of the U of A’s lively alumni chapter in Vancouver in 1925.

What we know

Seyer’s home near the UBC campus was “lovely and lively” and students often mentioned the warm hospitality of Bill and his wife, Blanche, whom he’d met while doing his PhD at McGill. (By the way, one of Seyer’s McGill research projects looked at the chemical composition of the asphalt in Alberta’s northern “tarsands,” as the oilsands were then called.) While at UBC, he saw potential in the emerging field of chemical engineering and helped start a department. In 1948, he moved to Los Angeles to be a professor at UCLA, where he specialized in the study of corrosion (and regularly whomped competitors half his age on the tennis court).

What we love

We love ballpoint pens, and Seyer’s work helped put good ones into our hands. When the pens were introduced in the 1940s, they used a wax-like solid for ink. Seyer developed a quick-drying, absorbent ink, patented the process and sold the rights to a company that was the forerunner of Paper Mate. Less well-known, according to a University of California website, is that Seyer became a consultant to Paper Mate, and his research influenced how the design of the pens.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.