On a snowy day in January, I joined my daughter's Grade 6 class on a trip to the Alberta legislature.

I had looked forward to it for many reasons. When I was in elementary school I had taken a similar trip, and I am given to nostalgia. I had worked in the building twice - once as a university student and again as a journalist.

Upstairs, we walked rather quickly past the galleries of esteemed men with grey hair. There is an excellent display about the Famous Five. But the longest stop was at a statue and plaque I had walked past hundreds of times but never noticed. The statue was of Crowfoot, the great chief of the Blackfoot Confederacy.

In French, our young tour guide explained about Treaty 6 and Treaty 7, about residential schools, about the Indian Act. My daughter paused at the line on the plaque, "In anguish over the declining position of his people … ." She is a collector of words, and this one - anguish - struck her.

The kids asked a lot of questions that day, but the best of them were in front of the statue of Crowfoot. I realized, listening to them, that these students knew far more about Indigenous issues than I did when I graduated from university.

When we lived in France, we went to the Mémorial de Caen, a war museum in the coastal city that was destroyed in the Second World War. On the day we walked the circular descent that charted Hitler's ascent to power, there were several busloads of German schoolchildren among us. I remember thinking: how strange it must feel to be German at moments like these.

A few years later, in the Apartheid Museum in Johannesburg, I wondered what it felt like to be a white South African tourist walking past the nooses hanging from the ceiling, images of blood and carnage set against images of privilege. That was me. My parents and grandparents. That is me.

In 2014, when the Truth and Reconciliation Commission stopped in Edmonton, I attended a few of the sessions. They were handing out boxes of tissues to those of us who listened. Afterward, in the halls of the conference centre and out on the street we said "unbelievable" to one another - as though it had all happened in another country. Then we went for tacos.

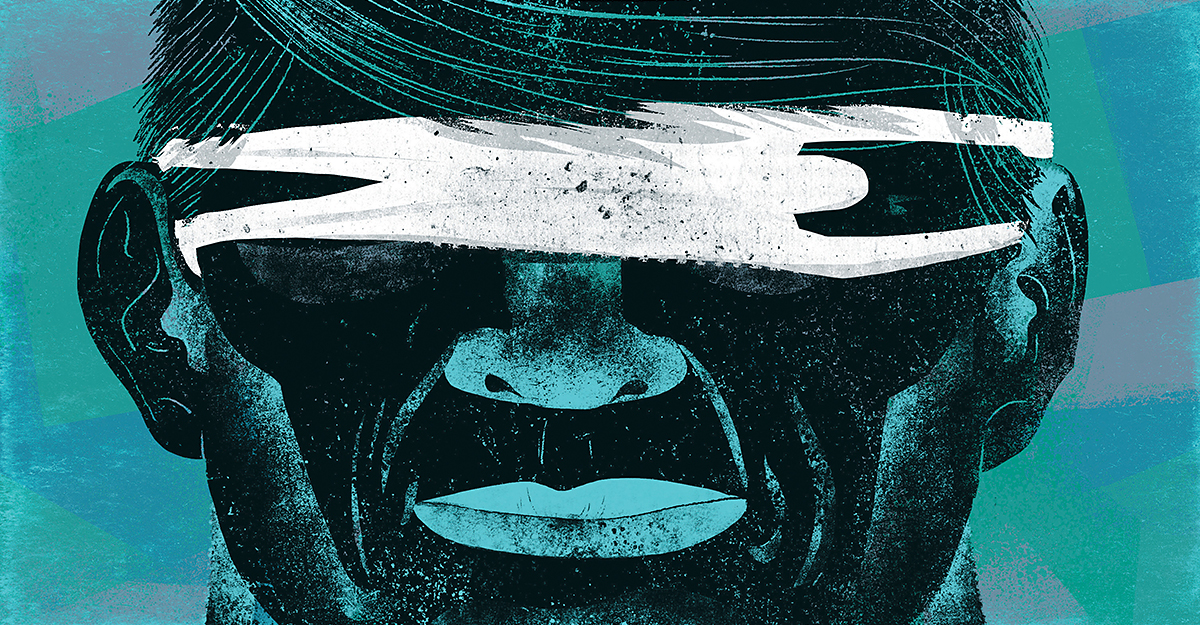

Where I grew up, when I grew up, racism was bad. A racist was the worst thing you could be. The villains in Hollywood movies were either bullies, communists or racists. But among most of the adults I knew, in my lower-middle-class industrial town surrounded by farms, jokes about Indigenous people were somehow OK.

This is how it feels to be a German at the Mémorial de Caen, to be a white South African at the Apartheid Museum: it feels like someone else did it. Those German schoolchildren were born long after Hitler committed suicide. None of the white South Africans walking through the Apartheid Museum actually hanged anyone.

I've toyed with this thinking myself. I didn't put anyone in a residential school. I don't make jokes about Indigenous people at dinner parties.

This is a dodge. While they never would have used this label, I come from a long line of privileged white people. I can find all sorts of marginalized groups in my family history but that is another dodge, a defensive retreat into comfort. I come from a culture of white privilege, and it has helped me immensely. It's why I was in the position to be asked to write in this wonderful magazine, and why I had the audacity to say yes.

In middle age, I'm in the same position as my 11-year-old daughter. We're both standing in front of the Crowfoot statue, feeling the word anguish, trying to understand. I have not yet figured out how I might improve things, apart from asking questions honestly and curiously, reading and fighting every instinct to form an opinion on an issue I know nothing about.

This is a lesson I've learned as an alumnus more than as a student: it is often best to shut up and listen.

Todd Babiak, '95 BA, works at a strategy company called Story Engine. His latest work of fiction, Son of France, is published by HarperCollins.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.