Stretched flat on the earth just outside the Saddle Lake Reserve two hours' drive east of Edmonton, I opened my eyes and gazed into the sky. The warm sun was overhead. I was soaking wet but could feel the prickly prairie fescue under my bare back and calves. There were voices nearby, soft and subdued, though one, that of a small child, Atayoh, was more animated. The sweat lodge was being disassembled behind me. Unable to move, I understood that a purification of some kind had just taken place. Elders and knowledge keepers had told us beforehand that inside the sweat's black void and volcanic heat we might be gifted with answers or struck by visions or pass out, or that ancestors might speak to us or that the Creator might heal a spiritual wound. But in stage after stage of the sweat, what I felt was a peeling away of layers - layers of experience, history, assumption, persona, misinformation. The lodge's total interior darkness meant there was only one place to look: inside. The chants and songs and prayers hit a hypnotic level by the time all the rocks were in the centre pit, glowing like molten lava starting to crust over. When the last prayer ended and the lodge tarp was pulled back, I was capable of forming only one thought.

Today, we start over.

The child's voice rose with joy. Atayoh was playing with his grandpa, Eugene Makokis, whose wife, Pat Makokis, '79 BEd, had invited me to the sweat. Atayoh was running around near the sweat lodge, carrying a small piece of birch, waving it like a wand and laughing. My brain was beginning to process again and I began to consider what the future held for a child like Atayoh. He was only two years old, but even a single generation ago he might have had just a few more years at home before being placed in a residential school. Another few years of playing with his grandparents, bonding with his mother, delighting his community. And then he'd be gone. His parents and grandparents might never have seen him again.

It was this way for 150,000 Indigenous children and their families across the history of the Indian residential school system, part of a practice that lasted for more than a century. The 2015 final report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, a seven-year undertaking, was the first real attempt to come to terms with how residential schools were used by the Canadian government as one tool among many to eradicate Indigenous culture, ceremony and identity. On the very first page of the TRC report, the authors note the residential school system is "difficult to accept as something that could have happened in a country such as Canada, which has long prided itself on being a bastion of democracy, peace and kindness throughout the world."

I saw that day, as clearly as I saw the perfect line of the prairie horizon, that non-Indigenous Canadians have a great many serious facts not just to acknowledge but to truly understand before there can be any talk of reconciling with Indigenous people in this country. Canada tried to erase Indigenous people by destroying their political and social institutions, seizing their land, moving populations forcibly, banning their languages, prohibiting their cultural practices, enforcing a foreign faith and attempting to dissolve their family customs and bonds at every turn. And that is on top of what took place at the residential schools.

I'd left the sweat lodge drained, an empty vessel. What stepped into that space was the truth. And there is no hiding from it anymore, for any of us.

Manifold crimes have been committed against Indigenous peoples in Canada for centuries, but why? Why did Canada do these things?

At the time of first contact, European colonizers believed they had divine authority (under a papal bull, a kind of public decree from the pope) to conquer and convert. It was thereafter the duty of European superiority to promote man's continuous progress - meaning, civilize the savages when and where you find them. Since Confederation, but even more pointedly during the greater part of the 20th century, it became legislative practice to erase Indigenous peoples, primarily for economic interests. It would have been (and still would be) fiscally impossible for the Crown to fully meet its treaty obligations.

It's important to understand that virtually everything that took place in a residential school, and many of the atrocities inflicted on Indigenous peoples since Canada's inception, have been the result of deliberate decisions at the highest levels of government. The crimes against Indigenous peoples cannot be dismissed as the actions of rogue priests or sociopathic schoolmasters. As the TRC states, "residential schooling was always more than simply an educational program: it was an integral part of a conscious policy of cultural genocide."

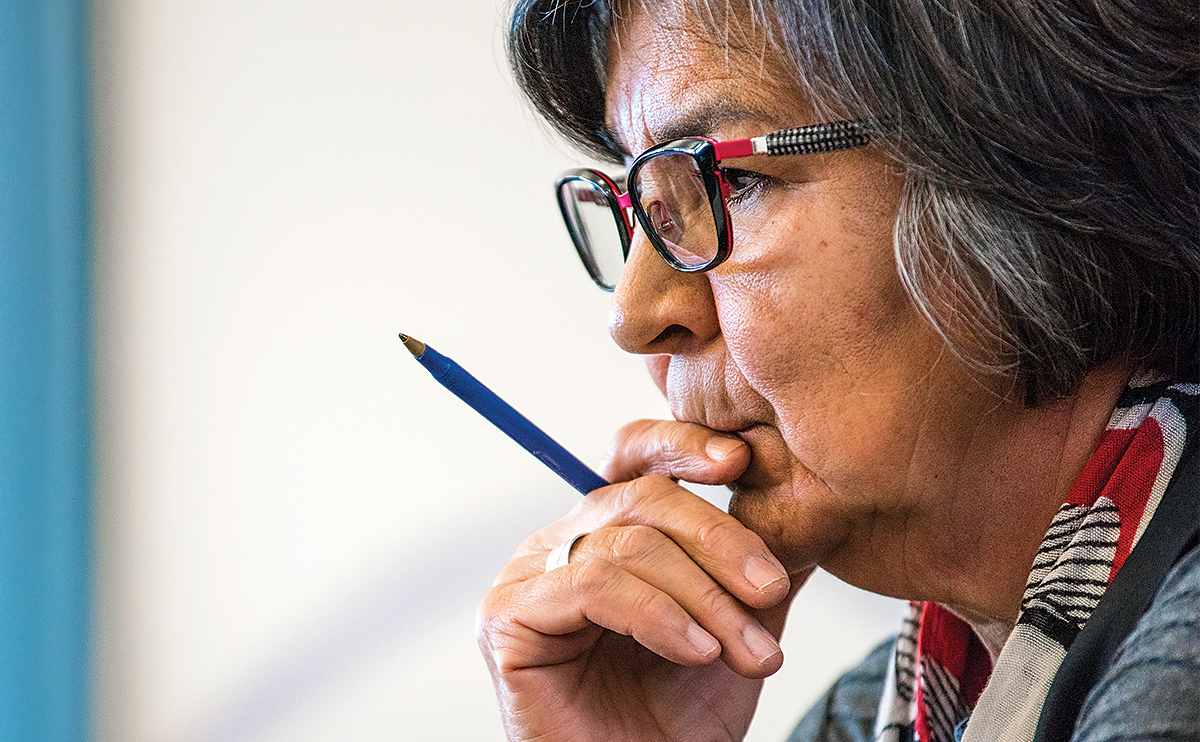

Last September, the University of Alberta hosted the second annual Building Reconciliation Forum, a two-day session that brought universities together with First Nations, Métis and Inuit leaders to wrestle with the question of how to address the 94 calls to action set forth in the final TRC report, many of which involve education in one way or another. As the first morning was getting underway, I ran into young Atayoh's grandmother, Pat Makokis, and Fay Fletcher, '84 BPE, '94 MSc, '04 PhD.

Pat Makokis wants her grandson, Atayoh, to grow up in a different kind of world.

Photo by John Ulan

Makokis, who is from Saddle Lake Cree Nation, went on to earn her doctorate in education from the University of San Diego and is currently on a three-year appointment with the University of Alberta to work in Indigenous relations. Fletcher, who is of white European descent, is associate dean in the Faculty of Extension and an associate professor focusing on education and Indigenous issues. They often work as a team to help the university, government and business find an ethical, intellectual and emotional space from which to begin thinking about how to make reconciliation possible. Typically, they lead discussions and offer presentations on history and current realities, and where each one of us fits into finding a way forward.

"It's possible," Makokis told me, when we met in Fletcher's office at Enterprise Square last fall, "that Fay and I are starting to have a bit of success because we've been doing this work together for so long. It's challenging, but it's exciting."

The first morning of the Building Reconciliation Forum demonstrated precisely how great the challenge is. We were reminded that Canada was, in large part, founded on the practice and profit of a process meant to erase a major roadblock to nation-building, namely Indigenous people and their treaty claims. Cultural genocide wasn't just something that happened in our country; it made our country.

From the words of Sir John A. Macdonald in 1883 when he told the House of Commons that "Indians" were "savages," to public works minister Hector Langevin telling Parliament, also in 1883, that if left in the family home, Indian children would "remain savages," to deputy minister of Indian affairs Duncan Campbell Scott telling a parliamentary committee in 1920 that "our object is to continue until there is not a single Indian in Canada that has not been absorbed into the body politic," we can easily see the pattern at work. The attempts at eradication continued unabated. The Canadian government used Indigenous peoples as lab rats for nutritional experiments in the mid-20th century. Even the 1996 federal royal commission, heralded at the time as a step forward, has had few, if any, of its recommendations met in full. But that's history, part of back then. We know better now, and we are smarter and more ethically inclined. Right?

Perhaps not. In 2008, then-prime minister Stephen Harper publicly apologized in Parliament to Indigenous peoples on behalf of the nation, but his government then proceeded to hinder the work of the TRC. In fact, the TRC had to sue the Canadian government in 2012 and 2013 to force it to produce documentation related to the history of residential schools. It took a judicial ruling to obtain much of the documentation that led to the TRC's final report, more than 900,000 documents in total.

Canada, meaning both the government and individual Canadians, has committed atrocities against Indigenous peoples under many covers. But through a process of cultural regeneration and spiritual preservation akin to keeping a single match alight in a hurricane, Indigenous peoples in Canada have somehow managed to survive. And now here we are. Thirty-five million treaty people - Indigenous and non-Indigenous alike - needing to heal from a dishonourable and contemptible past. Which leads us to a rather vexing question.

Now what?

Back at the Building Reconciliation Forum, Wab Kinew - politician, broadcaster and advocate - offered one starting point. Non-Indigenous Canada must "recover" from the myth of cultural superiority. "It still persists," he said. "It's still with us. There is a spiritual and intellectual legacy to Indigenous culture. And it's not too much to ask that people learn about the nations where they live."

Indigenous scholar Steven Newcomb put it a different way. The shared history of the two peoples, he said, has been about domination and dehumanization. "And if we can't tell the truth about that, there is no point having a conversation about reconciliation."

If Canada wants to reconcile with Indigenous peoples, in other words, we first need to know, and then accept, the extent and depth of what it is we are reconciling from.

Despite the sobering cataloguing of truths about Canada's past, it was nevertheless the point of the forum to talk about reconciliation, particularly in the post-secondary setting. Wendy Rodgers, U of A deputy provost, told the assembly about her own awakening, which began as she confronted her ignorance around the damage done by our colonial heritage. "I see the world differently," said Rodgers, "recognizing that our university, like our country, has absorbed some of the colonial assumptions about the superiority of white, western ways and the inferiority of Indigenous peoples and their cultural practices. We have to work to unlearn these assumptions."

Rodgers was touching on something central, namely that many of us are still trying to acknowledge the corrosive influence of colonialism, the belief that white, Eurocentric culture is superior to Indigenous culture. That culture is not superior. Yet neither is it inferior. We have to unlearn that way of thinking. If we can, maybe the learning can begin. And as I found out a couple of weeks later, the process will be painful.

Though the building now houses University nuhelot'įne thaiyots'į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills, some residential school survivors still cannot bear to enter the school.

Photo by John Ulan

The passageway was no more than 10 metres long, but in covering that haunted distance, the meaning of it all went through me like a spear to the chest. The TRC report became a living document when I was led through a former residential school a few kilometres west of St. Paul, Alta.

University nuhelot'įne thaiyots'į nistameyimâkanak Blue Quills has been an Indigenous-run educational institution since 1971, after a 1970 protest to demand the institution be turned over to a First Nations educational authority. In 2015, it became the first Indigenous-controlled university in Canada, owned and run by seven First Nations. But between 1931 and 1969, the facility was a residential school run by the Catholic Oblates.

I was being shown every room, office, hall, corner and closet by Corrine Jackson, the university's assistant registrar. She is a graduate of the university, but both of her parents and many other relatives and members of her community were placed there in the 1950s and 1960s. She has heard many of their stories.

The basement common room is a long, low space no longer in regular use, but for decades it was a dining hall. It brought to mind stories from the TRC report: example after example of children forced to eat rotting vegetables, rancid food or scraps left over from the meals of the priests and nuns, and then sometimes forced to eat the vomit from having to choke down that food.

The tour continued upstairs and on the third floor we paused beside a small storage room. It was once the infirmary. Jackson's mother, who is now 78, had broken her arm skating one winter, but the nuns wouldn't take her to the hospital. They left the break unset; it healed poorly and to this day her arm bends awkwardly. Jackson then told me another story.

"I never knew this until my mother told me recently, but I had an aunt, an elder aunt." It wasn't until Jackson's mother was able to visit Blue Quills with her daughter, after decades of avoiding the building, that Jackson found this out. "My mother had an older sister who was in residence with her. She was on her time, and she stained her petticoats and her underwear. As punishment, the nuns had her scrub clean her stuff and, after that was done, she was sweating. Then they threw her outside without a jacket for a few hours, and it was minus 30. She got double pneumonia and passed away. She would've been 13 or 14, my mom 10 or 11."

Number tags remain beside coat hooks in the downstairs mud rooms at Blue Quills university. Students at residential schools were assigned numbers and, for some, that became their only identity.

Photo by John Ulan

Jackson's mother was released from residential school not long after that because her own mother died. She was needed at home to raise her younger siblings and, at only 12 years old, help her aging grandparents. "I find my mom to be a true survivor," she told me.

Jackson paused before sharing yet another horrifying story - one that had been told to her - her voice faltering slightly. "Some sexual abuse happened on the third floor. My mother-in-law, she was five years old, her and her good friend used to hear this older girl who would cry at bedtime. A nun would come and get her and they would hear her screaming somewhere and then she would just come back and lay there. Anyway, they said they woke up one morning and the older girl just wasn't there. Her bed was empty. They asked where she was. The nuns got really irritated and said she went home … these were five-year-old girls."

Physical and sexual abuses were well-documented in the TRC report; for some residential school survivors, the TRC's sharing panel was the first time their accounts were actually believed. The commission identified fewer than 50 convictions for abuse at residential schools - a shockingly low number when you realize that nearly 38,000 claims of physical and sexual abuse were submitted as part of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement.

The commission also worked to uncover the truth about deaths in residential schools. Volume 4 of the TRC's report, Missing Children and Unmarked Burials, noted that fully half of the 3,200 children whose deaths were accounted for in the residential school system did not have a cause of death listed (tuberculosis accounted for roughly half of those who did have a cause listed). One-third of the deceased were not named. One-quarter were not identified by gender.

I couldn't help but think again of Atayoh's carefree laughter as the rest of us recovered from the sweat lodge and how, in a different era and just a few years older, he would have been forced into living conditions just like these.

We eventually made our way back downstairs to the rear exit and walked out toward a second building, the newer administrative and teaching centre of the university. I thanked Jackson for the tour. She shook my hand and we parted.

Blue Quills is now a university but being back outside felt as if I had escaped its past. The sun was shining, the sky was cloudless and the air was crisp. How would such a day have looked to a lonely little child 50 years ago, arriving here for the first time?

Teaching the next generation about ceremony, such as this smudge, is key to helping communities reconnect with tradition.

Photo by John Ulan

"Just keep walking," said Pat Makokis, half under her breath. "Walk at exactly the same pace. Don't slow down. And don't speed up. And whatever you do, don't start running."

The dog, a muscular animal, had trotted up and now followed us so closely it was almost on our heels. I could hear it panting. I turned around to look and could see the readiness in its heavy shoulder muscles. "Don't look back and don't stop," said Makokis.

We kept moving at the same pace, though trying to walk calmly is not at all calming. The animal followed us for about a hundred metres down the muddy, semi-gravelled road. Once we'd passed out of sight of its house, the dog stopped and stood in the middle of the road, watching us, almost daring us to come back that way.

We'd been walking around the townsite on the Saddle Lake Reserve for about half an hour. I had met Makokis at the hockey arena, from where we set out. She wanted to show me what was happening to the place where she lives, a place that had never been prosperous but that at least had once been safe.

In September 2007, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Among other rights - self-determination, language, equality and land - Article 21 calls on governments to "take effective measures and, where appropriate, special measures to ensure continuing improvement of their economic and social conditions." In other words, Indigenous peoples have the right to live a safe and comfortable life with access to economic opportunities.

Yet to walk the roads of Saddle Lake is to understand that many of Canada's Indigenous peoples do not have these opportunities. The roads are in worse condition than many an off-road hunting trail. The housing is squalid. One of the roads is blocked by concrete barriers to deny drug dealers quick entry and exit in residential zones, though it doesn't seem to have worked - there are worn tire tracks through the long grass in the ditch beside the barriers. And then there are the dogs. "The people who live here have dogs for two reasons. Either they're drug dealers or they're scared of the drug dealers and their dogs," Makokis explained. We stopped so she could point out some signs in front of the local grade school. "You see that?" she said. "That sign has no graffiti. That's because they were made by students, and they're signs about hope and perseverance and staying clean and respecting family. The gang boys don't deface those because a lot of them are still kids."

Makokis knows that some people see all of this as proof of stereotypes - but those people don't understand the complex legacy of the residential schools, how generation after generation of Indigenous children were taken from their homes and taught to feel ashamed of their families and their culture.

"I've been teaching about historic trauma for years, and I look at our community and it's so heartbreaking to see people in disparity and poverty and family violence and all these things. And I look around and I can see generations, three at least in some of these families, where they're traumatized so badly that it's rolling out in the problems in their families. And it's just heartbreaking. It's so heartbreaking because I understand. It's all about unresolved grief."

"Intergenerational trauma" is the term psychologists use to describe why the effects of residential schools continue to manifest in Indigenous communities. First-generation survivors develop coping methods, lifestyles and even parenting styles rooted in the traumatic experiences of the past. The next generation adopts these lifestyles and parenting styles and then inevitably passes them along to the generation after that. Makokis knows finding a way to break that cycle is key to moving forward.

"I look at my own family and I think, 'Oh my God, if people only understood that hanging onto culture is part of the answer.' Because to me, when I look at my family, how the hell did I end up with [children who are] a doctor and a lawyer? You know? We were poor like everybody else but we hung onto that culture. We could see the strength and the beauty and the teachings in that, in how we have to live our lives."

That tradition and ceremony have been a part of young Atayoh's life since the beginning. Makokis likes to say that her husband, Eugene, sang their grandson into this world. Like pretty much every other toddler, he loves to play dinosaurs but he also loves the drum. He just picked it up one day, displaying an uncanny sense of rhythm alongside his childish enthusiasm. He is a healthy, happy child and he is being raised in tradition. Makokis doesn't believe this is a coincidence.

As we continued our walk, she stopped and waved a hand over the houses we could see in front of us. "You know, it's not just about teaching white people about what happened. It's about teaching our own people about what happened, so that they understand why they are the way they are, and how they can change."

When we got back to our cars, we paused with doors open. "People need to know the disparity of what's happening to my people," she said. "You can go to Cold Lake and see what they're doing there then you can go an hour and a half down the highway to here, to another reserve, where you can witness the direct effects of poverty and trauma, where we barely have drinkable running water. When you have economic opportunities, the community collectively can figure out its growth plan. If there were the same opportunities on every nation, you would probably see those communities thrive."

A cold wind was blowing across the parking lot. We said goodbye and I drove back through town on the kind of road the average Albertan would write outraged letters to elected officials about. I decided to take the back way through the reserve to the main highway, but wasn't sure how to get there. The road signs on the edge of town weren't much help; the information was obscured by graffiti.

Eugene Makokis sang his grandson, Atayoh, into the world.

Photo by John Ulan

A 90-minute drive northeast of Saddle Lake lies the Cold Lake First Nation. The reserve sits near the town of Cold Lake on the Alberta-Saskatchewan border. It also straddles huge swaths of the Cold Lake Air Force base, is home to numerous oilsands operations and has reached a land settlement agreement. All of this adds up to opportunity and, in 1999, leadership created Primco Dene, a company wholly owned by Cold Lake First Nation, with the express strategy of working with industry. On the same site is a casino and new Marriott hotel, both run by the band.

As we sat in the boardroom of their modern offices, natural light spilled in through floor-to-ceiling windows, all the better to admire the burnished wood table. A bottle of chilled spring water had been placed in front of me, and various members of the Primco executive team - some white, some Indigenous - sat around the table.

Commencing with 50 employees in the catering and janitorial businesses in 1999, Primco Dene now employs more than 800 people, mostly Indigenous, from 50 different communities in Western Canada. It operates 15 separate companies, which include security and emergency medical services as well as janitorial and catering services. Primco Dene has turned the Cold Lake First Nation into a financially sound body, an Indigenous success story operating on its own terms.

I asked what the biggest challenge was to working as an Indigenous company in a predominantly white industry, the oilpatch. "To me, the biggest challenge is education," said Larry Henderson, Primco's vice-president, commercial. "We need to get good information out to everyone but particularly people at the heads of companies - proper information, so that we change the perspective of things. There are so many prejudices out there, so many misperceptions."

"And really," said Mike Brown, Primco's security manager, "you can throw money at things, but I think the place you've really got to start with the education is at the kindergarten level. But you can't just start it and then leave it. You have to follow up. We have to teach Canadians that Indigenous people have fulfilled their part of the bargain, but we in no way have fulfilled ours." Not to mention, said Tammy Charland-McLaughlin, Primco's vice-president of operations, that there are many misconceptions around fiscal issues.

It's hardly surprising there are misconceptions. As I found, First Nations funding is complex and convoluted. Essentially, the federal government holds First Nations money in a trust. This money originates from a variety of sources, including the sale of what was originally First Nations land, and resources from reserve, treaty and traditional Indigenous land. As far back as 1911, Duncan Campbell Scott spoke to Parliament about "the Indian Trust Fund," which at the time held $56,592,988.99.

The details of what happened to this fund and whether it evolved into something else (the federal government refers in its financial documents to the "trust accounts" that it administers), how much has or has not been paid into these funds or trust accounts in the century since Campbell Scott's report, and even the process by which the federal government today disburses transfer payments, are all difficult to confirm. What is clear is that moneys currently transferred to First Nations communities are generated, in large part, from funds that they, in fact, own. Once these moneys are disbursed, each individual nation then assumes the responsibility to pay for services such as education and health. Of course, all of this varies from community to community and does not account for Métis, Inuit or First Nations peoples living off reserve.

The bottom line, says Charland-McLaughlin, is "the general public thinks taxpayers' dollars pay for our nation, but they don't."

Since the release of the TRC's final report in 2015, there has been a vast amount of activity - forums, books, essays, workshops, community-building exercises, school visits, government work, think-tanks, post-secondary summits, and on. If one theme has begun to emerge, it might be this: Indigenous people feel that prior to any breakthroughs on genuine reconciliation, a first step would be for non-Indigenous Canadians to accept, and perhaps even attempt to understand, the legitimacy, beauty and depth of Indigenous culture and history.

"The public education system plays a huge role in shaping the narrative of what this country is."

Of course, these lessons are unlikely to be absorbed without friction. Pat Makokis and Fay Fletcher wrestle every day with questions of how to educate and through whom. They can recount numerous anecdotes of difficult situations they've faced in which non-Indigenous people have challenged the legitimacy of Makokis's message or Indigenous people have challenged the right of Fletcher, as a moniyaw or white woman, to even speak to the subject. Makokis and Fletcher use the term "settler-ally" to describe Fletcher's role and relation to the issue and process. It means someone of European descent who is an ally of Indigenous people in working to create change. This term can also be used as "settler-ally work," as in the work undertaken together.

"Pat knows my role and I see hers," Fletcher told me, "and we can seamlessly privilege both those views. I don't know anybody who works like Pat, that there is a place for everyone to bring perspectives and knowledges that are important. I've been in a space where there was a lot of anger expressed. But Pat very quietly said to me, 'This is not yours to carry.' And so I learned to sit, to listen, to receive, but not to be harmed by it - or as little as possible. I know it's an old saying, she's got my back, but she does."

I asked them about times when they were team-teaching or speaking together, when they encountered difficult moments, or even when they might have seen the light bulb go on in an educational setting.

"Well, the thing you have to realize first is a lot of the problems revolve around western methodology," said Makokis. "Universities and academies that maybe don't believe Indigenous knowledge and teaching is rigorous enough because it's mostly oral. But then sometimes we end up working with people - academics, say - who realize that there is another way."

"What's funny, though," added Fletcher, "is that some of these people who are getting it are only getting it at the end of their careers. They look around after decades of doing things the western way and maybe they see what's being done to our collective mother, our Earth, and they realize, 'Oh my God, Indigenous people are the poorest on this land and yet they're fighting this fight.' "

The biggest barrier in pursuing reconciliation through education, said Makokis, is simply the lack of knowledge of who Indigenous people are. "When we don't know each other, it's easy for someone to walk down a street and see a Native man panhandling and think that's who we all are without realizing what that man's story is."

We stood up to go, but Makokis offered a parting thought. "The question that I try to get people to think about is, 'How have we been indoctrinated, all of us, by what we've been taught?' "

That's certainly a question Evelyn Steinhauer, '02 MEd, '07 PhD, has been grappling with of late. Steinhauer is an associate professor in educational policy studies in the Faculty of Education at the U of A, as well as associate chair (graduate co-ordinator) and the director of the Aboriginal Teacher Education Program. I met with her in her office on the seventh floor of the education building one afternoon as the early winter light was bleeding into evening. I asked her to tell me about the controversial events that have surrounded one of the faculty's mandatory courses, EDU 211: Aboriginal Education and the Context for Professional Engagement. The course description says students will develop "their knowledge of Aboriginal peoples' histories, educational experiences and knowledge systems, and will further develop their understanding of the significant connections between such knowledge and the professional roles and obligations of teachers."

All of which sounds logical and beneficial. Not to everyone, apparently. In the 2016 spring session, a student went to Rebel Media, the website of provocateur Ezra Levant, '96 LLB, and complained that the course was one-sided and that it was set up only to hector non-Indigenous people. The student's action created animosity and fear. Professors had to go to class with security. The university made moves to protect the faculty, but it also investigated the student's claims that he felt unsafe and had his rights compromised. Steinhauer is still not convinced the university realized the seriousness of the threats.

"In the end," she told me, "we were the ones investigated because we made the student uncomfortable so we must've been doing something wrong. It went to the police and the police did an investigation. It didn't go any further."

The situation stands as an apt reminder of the many inherent challenges in the reconciliation process - in this case, how to use the power of education to create equality and tolerance in the next generation. Or, as Primco's Mike Brown put it, we need to start at the kindergarten level. But if the teachers don't believe in it, don't get it, the racism will be perpetuated. The reality, said Steinhauer, is that we will never have anything even close to reconciliation until we build meaningful relationships.

"There's been a lot of broken, troubled relationships, but people just need to get to know Aboriginal people. We're really good at walking in the white world because that's how we've learned to survive. But how often does a non-Aboriginal person come walk in our world? When you walk in each other's worlds equally, then that's when relationships will really begin to develop."

Classes for that term had ended, which meant that when I left Steinhauer's office, the south education tower was unusually quiet. The halls were unoccupied, but it didn't feel peaceful.

The Faculty of Extension offers certificates in Indigenous Community-Industry Relations, and students must complete five non-credit courses on what you might call entry-level Indigenous issues primers. In late November 2016, I attended the four-day Indigenous Laws, Lands and Current Industry Government Relations course. About 20 per cent of the 30 attendees were Indigenous, the remainder white, most working for various government departments, local businesses, small accounting or law firms. A couple of the Indigenous attendees worked for their band councils. In the opening sharing circle, as person after person said a few words about why they were there, it became clear that "knowing more, understanding more" was at the heart of their attendance.

As a legal scholar, Janice Makokis, '05 BA(NativeStu), (Pat's daughter and Atayoh's mother) walked the group through the history of Canada's legal relationship with Indigenous people. Kurtis McAdam, a Cree knowledge keeper, also led sessions. After an early career working to develop Indigenous programs in the correctional system, he now spends his energy trying to locate elders to draw out and preserve the knowledge residing in them. As McAdam detailed the history of how Indigenous oral law developed over centuries, and how it gets interpreted today, the group was moved by a story he told: centuries ago the Blackfoot and Cree, tired of civil war, agreed that they had to cement peace between tribes and did so by sending their young children to live with each other, so that each tribe knew it could never attack the other because they would be killing their own children.

Over the course of the four days, there were a number of emotional moments, particularly when one or two of the Indigenous participants told the group that they had come to the course to learn about their own heritage, and that they themselves had been shocked to learn the details of what had happened to their people - not just in residential schools but over the course of the entire relationship between Indigenous peoples and Canada. More than once, a white participant would say something like, "But how could that happen?!" To which Makokis or McAdam would say, "Good question."

The most pointed moment of the class, however, came on the second day. McAdam was talking about the difficulty of trying to preserve knowledge when it is stored in oral tradition. "And it doesn't help, obviously, when your people are subjected to cultural genocide."

At that point one participant, Michael (not his real name), put up his hand. A curious and genial man who looked to be in his late 30s, he had told the group on Day 1 that he was an accountant working with a firm in St. Albert. He had enrolled in the course because he wanted to know the truth about things.

McAdam stopped when he saw Michael's hand up. "Yes?"

"I have a question," said Michael, choosing his words carefully. "You use the term 'cultural genocide.' That's a pretty big term, you know, genocide, the Jews, the Nazis. What exactly do you mean by it when you use that term in this context?"

A slight tension came over the room.

McAdam thought about it for a minute. "OK," he said. "Let me explain it like this." He took his collection of small handheld drums and a couple of pipes. He put them in the middle of our circle. "Imagine that all these things are your culture and your people. Take away your sense of family …" He picked up one of the drums, handed it to a participant and asked him to go stand alone in a corner. "Then you take away language …" He handed another drum to another participant and asked her to stand in a different corner. "Then you take away cultural practices …" Again, the same, this time with Michael, who went to the farthest corner away. "So, you do all that. And then you take all the little children, every single [child] in every family, and you take them away from their parents, and you strip them of everything they know and have. And you do that for the next decade with every child. And then you do it for a century and a half." He looked around the room and pointed to the people standing in the corners - culture, family, language - and then back to us. "And so, all of you, you're who is left. You have no children, you can't practise your culture, you forget how to parent, your language is against the law, you're not allowed to dance or sing or tell stories, you're forced off your land but not allowed to farm. Your money is stolen from you. Everything that you were, everything that your people were, is gone. And it's all been taken away from you under a system of law that you don't understand and didn't agree to and that has been designed to remove you. And now that's your life."

He stopped. The room was quiet. He asked people back to their seats.

"Does that help answer your question?" he said to Michael.

Michael was hunched forward in his chair. "… I guess so." He sounded unconvinced, but also a touch insulted, as if part of him was thinking, But wait a minute, it wasn't me who did that to you. After lunch, Michael did not return, and I assumed he was simply doing what most of Canada has been doing for decades: shutting out the truth because it's too painful to confront.

But then there he was the next morning, back in his chair sipping a coffee. We started the day with a sharing circle. There were many tears shed. There was outrage. But more than anything else, there was determination. A commitment to not go back to the same place we'd just come from. "I am going to go back to work tomorrow," said one woman who worked with the City of Edmonton, "and every person in my office is going to know what really happened. They're going to know because I'm going to tell them."

When Michael's turn came, he had things to say.

"For the past 15 years, every professional development course I ever took was about accounting. But this has been a little different." He paused and the group chuckled. "The more you learn the more frustrated you become. I just don't know how white people can't get it, can't get what this is about. Being here has been … well, it's been life-changing."

Makokis and McAdam thanked Michael. And then we kept moving around the circle.

Vincent Steinhauer is president of Blue Quills, the first Indigenous-controlled university in Canada.

Photo by John Ulan

Michael's epiphany was something I understood and could relate to. When I had finished my tour of Blue Quills with Corinne Jackson, I had gone back to the office of the university's president, Vincent Steinhauer, '01 BPE, '04 MA. I went in and slumped in a chair. The view out his window was of the back of the old school.

"Enjoy the tour?" Vincent said, his eyes crinkling a bit with his own joke.

I told him that I was struggling. "I don't even know how to say it," I said. "I just feel … I feel so ashamed, so sorry." The emotion was thickening in my throat and my next words were hard to squeeze out. "I feel inadequate, not even qualified or that I have any right to even tell you what I'm feeling or what any of us should do …"

"That's the best place to start," he said quietly. "With the inner debate. To let people know how conflicted and inadequate you are. That you're searching for answers just like they are."

I nodded, glanced back out at the old building. "I understand how some people, survivors, just can't go in there."

"Yeah, there's some friction between the generations, actually, because some people are scarred by it and want to tear it down. Some of those people are so damaged that they walk the streets under the influence, and not just this town, but in many cities and towns in Canada. And people blame them for what Canada has done to them.

"But others see this place as a symbol of survival and education."

It made me think of what Jackson had told me as we parted. "To me, this is actually a positive place, a place of success," she'd said. "I got two degrees here. I came for upgrading. I was a dropout. And I managed to pull up my socks and get things done. And now enrolment is growing. We're becoming more well-known. And all those things that were taken away - the ceremony, the identity - that's what students learn here, to grow, to come into the cultural identity that was lost during the residential school time."

Atayoh Makokis plays among the dancers at the annual U of A round dance. The ceremony, traditionally held in the winter, is meant as a time for healing and remembrance for the community as a whole.

Photo by John Ulan

The transformation of Blue Quills from a repository of shame and horror into a conduit for knowledge and hope is not just uplifting but symbolic. It's what needs to happen in the hearts and minds of Canadians. A few weeks later, I asked Janice Makokis over coffee what such a person would look and act like, a white person who has turned that corner.

"Well, I guess for starters, they'd understand their privilege. They would understand the privilege they carry as a non-Indigenous person. They would understand the history and issues of Indigenous peoples. They would know when to use their privilege in places and spaces to advocate for Indigenous peoples if there is not an Indigenous person there. And they would know how to work with Indigenous peoples in a respectful way where they don't try and control the agenda. And they would listen, respectfully, and genuinely want to learn our perspective and values."

"What's so hard about that?" I said, laughing.

She laughed, too. "You know, in this process of coming to understand the history and going through this decolonization process, I realized that the public education system plays a huge role in shaping the narrative of what this country is and the relationship between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people. I remember a quote - someone was giving a talk about Indigenous ways of knowing, and how to incorporate that into a teaching curriculum. And the presenter put up a slide that said 'White privilege is having white history be required and Indigenous history be an option.' The public education system is responsible for a lot of the issues, so that trickles up to the universities, and then their role is to train teachers to understand it all from a different lens. Because then they go back in the education system and teach the students."

It's too much symbolic weight to place upon the head of one child, yet I couldn't help but think of Atayoh and the world he'll occupy by the time he gets to his post-secondary education. Will he follow his mother and grandmother to the U of A? Will he be going to a university that celebrates Indigenous culture? Will he find municipal, provincial and federal governments in which positions of actual power are held by Indigenous people? Will he be able to walk the roads of Saddle Lake and not be tracked by the pit bulls of drug dealers? Will he attend a political science class thinking that he might one day be Alberta's premier? Or will he be sitting in a classroom wondering why he's fighting the same fights as his mother and grandmother?

I thought back to those moments immediately after emerging from the sweat, when I'd first met Atayoh. I'd watched him as he scampered around the grassy circle, waving his little arms, his black hair flopping around in the breeze. He was whooping with delight as his grandpa pulled his stick away from him and gave it back, teasing him. Atayoh zipped here and there, waving his stick as if it were a magic wand. The simple joy of it all was visible on his face, the joy of imagining that one swoosh of a stick could change everything.

If only it were that simple.

-

New MOOC focuses on Indigenous Canada

Sign up for a free U of A massive open online course that explores Indigenous peoples' history and contemporary issues.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.