I have a confession to make. It’s not what you think, although I admit I have no idea what you’re thinking. But I imagine this isn’t what you’re thinking, since the word confession evokes images of a priest and sinner, a chastened figure who has committed an action so shameful it can only be spoken of in whispered tones from behind a latticed panel. My offence is not sinful enough to warrant penance, though it’s true that my atonement involved countless hours of ruthless moral interrogation, some of it even from me.

Here’s what happened. When I was in my undergrad years in the Faculty of Arts, the reading loads were enormous. I recall a prof once assigning a 700-page biography of Freud, which he wanted us to read by the following week. He tested us by snapquizzing us on things like knowing Freud’s address in Vienna (“Berggasse 19! You need to do better than that, professor!”). Among the various barriers to academic success that I faced as a university student — which included sloth, distractibility, television, beer, sports and women — was that I was (and remain) a much slower reader than you might think, given that I’ve become a writer. Though my grades may have indicated otherwise, my problem was not one of comprehension but rather that I enjoyed reading, often to the point of rereading books I particularly liked. These were the days when deconstructionism was the rampant literary theory on campus and admitting you were reading a novel for something as dopey as pleasure was like saying you enjoyed the workout of breaking rocks in prison.

On top of being a slow reader, I was young. And I don’t mean age-young, though I was. I mean experience-young. I was a reasonably self-aware person but still a kid who hadn’t experienced much in the way of young love or young heartbreak or any real angst beyond the standard-issue post-teen stuff. My parents were together and happy. I got along with my siblings. I had a couple of weird relatives, but who didn’t? In other words, I was a pretty green banana. Then came a comparative literature course with one of my favourite profs, a lovely man named Edward Mozejko. And on the reading list was The Brothers Karamazov.

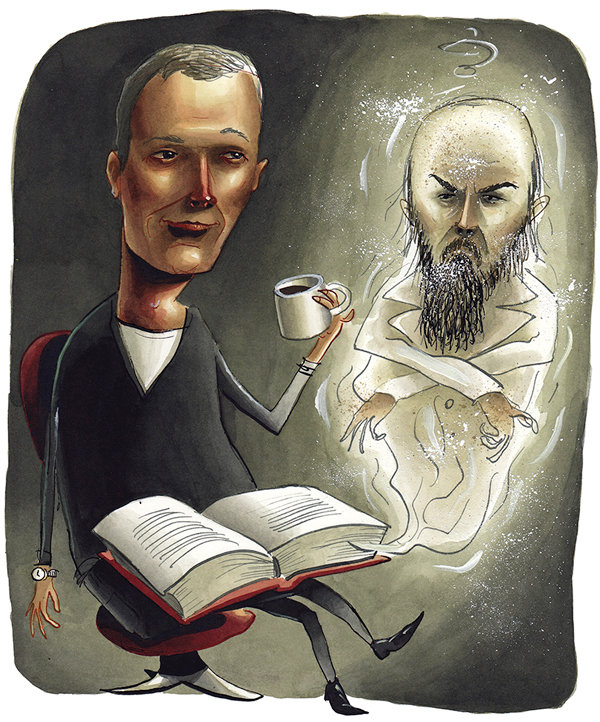

For those of you who don’t know, this is one of the towering works of world literature, widely considered Fyodor Dostoevsky’s masterpiece. It’s a heavy book. Literally. When I picked it up at the campus bookstore, it felt as if I was doing a bicep curl. You know you’re in trouble when you assess how long it’s going to take to read a book by its weight rather than number of pages. Mozejko, of course, assigned an essay on The Brothers Karamazov. I don’t recall what the precise topic was, what my mark was or what Mozejko had to say about my essay. But although I did pass the course with an acceptable mark, I left carrying a horrible secret. This may have been decades ago, but my crime has been like a tiny fissure eating away at the ethical dam of my life. I have finally decided to end the torment and confess to myself, my family and my community. I never finished The Brothers Karamazov.

There. I’ve said it. I feel better already. A weight has been lifted from my soul! Glasnost!

The reason I didn’t finish the book was that Mozejko gave me permission to not finish. Well, that’s probably not exactly how he’d characterize it. We were talking about Marcel Proust one day, as one does, and I happened to mention to Mozejko that I had only read the first few hundred pages of Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past and had never finished the remaining thousand pages or so. Now, Mozejko is a man who speaks about a dozen languages, a man of immense intelligence but with great kindness and humility, and he said to me, “Oh, that’s fine. With a book like that, the point is really just to taste it. You don’t go to a buffet and eat the whole thing.” It was liberating. You only had to taste something, not eat it whole! So I took that as my cue to drop The Brothers Karamazov like a hot samovar. I have no idea how I managed to write an essay on it, but whatever I wrote must have focused on the first couple of chapters because that was all I read.

And yet I never forgot it, probably because the real reason I didn’t finish it wasn’t because I was a slow reader, but because the book unsettled me and I didn’t know why. It was intense, intimidating, and I’m quite sure I just didn’t understand even the few bits that I read.

What I mean is that although I was intellectually equipped to understand it, I was not emotionally equipped to understand it. But there it sat, on my shelves, moving from apartment to apartment while I was still a student, then from city to city while I went to grad school, then back to Edmonton when I got married and started working, then from our first apartment to our first house, then to our second house, where we still live. It has moved from one home office to another home office, from one bookshelf to another bookshelf. But no matter where I went, it came with me, and I never questioned why. It was The Brothers Karamazov. That was reason enough.

Over those decades, whenever someone asked me if I’d read it … wait a minute, check that. Literally no one ever looked at my bookshelves or asked me if I’d read it. But whenever it came up in conversation … hang on, check that, too. It never came up in conversation. I finally realized I could trace the slight spasm of guilt I’d always carried about not having finished the book all the way back to Mozejko’s course. That, my friends, is precisely the germ of guilt that Dostoevsky might have written a 900-page novel about. Count yourselves fortunate to be subjected to only a few hundred words.

Then a funny thing happened this past Christmas. I pulled the book off my shelf and started reading it. I can’t even say why. There was nothing momentous about it. I just saw it one day and realized that I was ready to read it. The time had come. Was it pandemic-related? Age-related? I don’t know. But let me say this: I now understand the fuss. It is a huge novel in every way, shape and form, and I am now old enough and have experienced enough life to understand it. I have gone through enough joy and love and disappointment and pain in life to appreciate what Dostoevsky evokes. The novel is a human cry of ecstasy and despair, of love and hatred, of success and failure, of desire and repulsion. It is compulsively readable, bottomlessly thought-provoking and yet, in a strange way, quite life-affirming, even though it’s about trying to figure out which son killed his father. It’s worth the effort.

The great literary critic George Steiner once said to his students at Harvard: “Who among you has never read this book?” One student remembered that most of the class raised their hands, almost embarrassed, thinking they were going to be called out by their professor as substandard. Instead, Steiner sighed: “I envy you so much, you will experience this masterpiece for the first time, and there is nothing else in the world like that.”

The bigger takeaway for me, in this confessional moment, is that in life our learning has so much to do with when doors are open and when they are closed. If they are closed, there’s usually a reason and bad things tend to happen when you try to force your way through a closed door. When they are open, don’t hesitate, stride through! I wasn’t ready for The Brothers Karamazov when I was 21 and part of me surely sensed as much after reading a chapter of it. It’s too harrowing a look into the human psyche for a kid to comprehend.

In the end, the point really isn’t even about finishing or not finishing something, it’s about letting your experience be your own. There are plenty of things I have started that overwhelmed me — that I couldn’t finish. But that doesn’t mean they were less impactful because I didn’t complete them. I haven’t finished Moby Dick or Don Quixote or cleaning the garage. They’re part of my life and always will be. And what’s the downside of admitting that we can’t finish everything?

Would my life have been materially different if I’d told Mozejko that I’d only read the parts of The Brothers Karamazov I needed to in order to write the essay?

I mean, what’s the worst that could have happened? I suppose he could have reversed my mark and failed me. Which, I suppose, might have lowered my GPA such that I would not have got into grad school. Of course, maybe then I wouldn’t have travelled to Toronto and Scotland, taken that rewarding road, returned to Edmonton, met and married my wife, had children or had this wonderful life.

On second thought, here’s my confession. I don’t have any regrets about waiting so long to read The Brothers Karamazov from first page to last. Now, as for War and Peace …

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.