I've never been what you'd call buff. Or muscular. Or toned. Or … OK, I think you're getting the idea. My running joke for the last decade or so has been that maybe the kids at the gym could show off a six-pack, but I had a full keg. Still, despite the general lack of sculptural integrity on offer, my body has held up and mostly done what I wanted it to do over the years, none the worse for wear.

Or so I thought.

It has now come full circle, and everything I've done in my life has physically coalesced into one pressure point. It has been a journey of decades, really. From horsing around with my brothers in the basement when we were kids, to playing goal in soccer through my teens and 20s, to 40 years of golf and squash, to lifting kids into and out of cribs, carriages, car seats and beds and tossing them around the yard as they shrieked with delight. Throw in working on fences, major home improvements and a few hundred reps of driveway shovelling. I should have known it was coming. Actually, I did know it was coming. I spoke to my doctor about it in the late winter of 2017. "My shoulder is really sore," I told him. "What do you expect?" he said, ever the laconic old-schooler. "You're old."

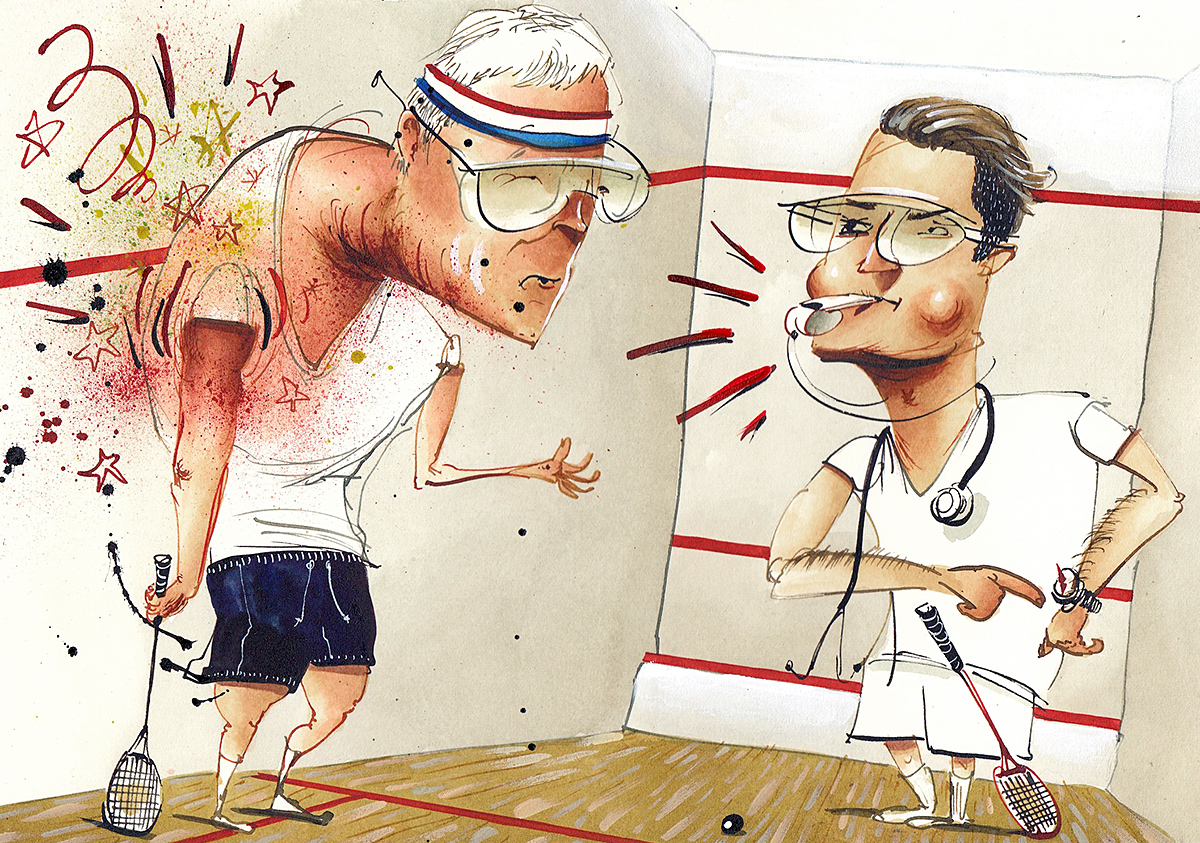

A wise man would have taken a break, which was why I ramped up my activity. I was on the court three or four times a week, playing squash in my local league. As always seems to be the case these days, I was up against someone substantially younger and, being of neither sound mind nor body, I was trying to keep up. Near the end of the second game, my spry young opponent hit a high lob from the front of the court, pushing me deep to the back. Backpedalling, I hoisted my racket up and over and behind my head, reaching, straining, swinging as hard as I could.

Let me pause to note it's not often that you actually hear something go wrong in your body. We feel such things all the time, but rarely do we hear them. What I heard was a discernible snapping sound, like an old piece of taffy that had been violently torn asunder. It was immediately clear to me that something bad had happened. The sound was so unnatural it made me queasy. The pain was intense. I couldn't lift my arm above shoulder height. It felt like some ogre had torn my arm off and was beating my socket with the stump.

Of course, I finished the match. Hey, I never said I was the most cerebral athlete. Afterwards, one of my teammates, a physiotherapist, did a quick assessment, subjecting my arm and shoulder to a series of peculiar and painful tests. "My quick assessment," he said, "is that you're screwed, buddy."

He was right. An MRI revealed a severe tear of the rotator cuff, the set of muscles and tendons that keep your shoulder in place and allow you to do things like … well, like everything. And it wasn't just one torn tendon, but two. I also had a badly damaged bicep, as well as various bone spurs. The fully torn tendon had retracted back behind my shoulder blade and would soon shrivel up like an old piece of bacon if not repaired. It was decided surgery had to happen right away.

The surgery was like a TV show, and I was both observer and participant. After the needle went in, the anesthesiologist told me to count to 10, laughing that I wouldn't make it. I counted to five and turned my head to her to say, somewhat worried, that it wasn't working. I opened my mouth and then woke up in the post-op recovery room.

Which was when the novelty of the whole thing wore off and I began to fully realize what the next year of my life was going to look like. This began to dawn on me around the time the second shot of morphine wore off. Trying to sit up to get out of bed and go to the bathroom — picture Napoleon crossing the Alps in the winter — drove home what I was going to have to learn to make it through the next year with both shoulder and mind strong enough to use. I was in a sling for six weeks and never slept more than an hour or two at a time. The pain was constant and, at times, sharp. My right arm (I'm right-handed) was a useless sandbag roughly stitched to my torso. A couple of weeks into rehab I wondered if I'd ever be able to lift a cup of coffee again, let alone play sports or garden. (Although not having to vacuum or drive kids around was a minor compensation.)

And let's keep things in perspective: it was a sports injury. People are suffering from real injuries and real tragedies every day all around us; those are things that truly matter. Nevertheless, the situation presented itself as an opportunity to see life through a different lens. I had a lot of time to think and to live in ways I normally wouldn't. On holidays in the Okanagan, I'd typically have been running, cycling, golfing, water-skiing. I couldn't do any of those things, so I went on long, slow walks. I studied the effect of the breeze on the lake. I learned the names of a couple of plants. I went on a couple of long hikes. I conducted a longitudinal research program into why a martini tastes so much better at 5 p.m. than it does at 9.

It wasn't exactly sudden, but somehow I ended up looking at the world in a slower and perhaps more contemplative way, although no one is ever going to mistake me for a Buddhist monk. One day a couple weeks after the surgery, sitting at home trying to figure out how I was going to get out of a chair, I actually did stare at my belly button for a few minutes. The mysteries of the universe were not revealed to me, though I did notice that I could sink my index finger into it up to the first knuckle.

I was also put on a rehabilitation program that seemed to me almost fable-like in its relevance to life in general. It was all about slowness, taking small, sure steps rather than leaps, progressing by the subtlest of degrees, making sure part 1 was achieved before moving to part 2. I am probably like most people in that I am patient in some ways and impatient in others, but this enforced patience in recovery became almost meditative. I would routinely do the same 10 or 12 exercises over and over, every day, hundreds of them at a time, pushing only so far, before seeing my physio again — at which point she would tell me to keep moving at the same pace. Over the course of months, I rarely seemed to make any noticeable leaps, but one day my physio announced I was ready for pushups. I was astonished. The overt moral of the fable, I guess, is obvious — that slow and steady wins the race — but the greater insight for me was how difficult it actually is to go slow and steady. It's not the easy way out. Don't ever be fooled by someone who says they plod along; they probably know exactly what they're doing and it wouldn't be such a bad idea to follow along at the same speed.

And although I'd rather have been golfing, cycling and running, there were other rewards to taking it slow that I'd never have otherwise uncovered. I guess for lack of a better word, I was forced into a more intense "noticing" of my environment. I admit these are perhaps idiosyncratic observations, but I noticed how little noticing actually takes place in our world. I had to take the bus around town for six weeks, being unable to drive, and I saw well-behaved but self-absorbed teens who missed an opportunity to offer a seat to a senior. Unable to type or write, I sat in coffee shops where I saw friends who must have taken the time to get together but who then spent it checking their phones. Philosophers have often talked of the ability to see deeply into the reality of the world. The reality that I observed was plain; we are connected at one level but disconnected at another. There is much theorizing about this, but it's profound when you observe it daily in tiny little interactions. I think being in a situation where I had nothing else to do but observe put me into a place that might be called being present. And I like to hope that I'll stay there.

Having said all that, my physio says my shoulder should be strong enough by January to return to squash. I can't wait to get back on the court. The guy that did this to me is toast.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.