Microscopic inventions, itty-bitty facts, pocket-sized solutions to big problems — the U of A is full of reasons not to underestimate the small stuff. The story you're about to read is one of many that highlight the wondrous and surprising ways tiny things are making a big difference.

Good things come in small packages, especially when you’re talking about some of the tiniest research and artifacts on campus. From nanofibres engineered to ward off bacteria to a book no bigger than a postage stamp, campus is full of tiny wonders that solve big problems, answer ancient questions and inspire curiosity.

Light reading

Antiquarian bookseller Hugh Anson-Cartwright, ’10 LLD (Honorary), donated this 1817 French almanac to Bruce Peel Special Collections in honour of his friend Jeannine Green, ’77 BA(Spec), ’80 MLIS, when she retired as the head of special collections. The 26-by-17-millimetre book contains songs, eight full-page engraved illustrations and a liturgical calendar listing saints’ days and other feasts. The miniature case (third photo) was created by alumnus and bookbinder Alexander McGuckin, ’93 BA, ’95 MA.

Pasta-sized prehistory

The U of A is home to more than 15,000 trilobite fossils, some of which are displayed in the Paleontology Museum. Some trilobites, an extinct group of ancient sea dwellers, were less than three centimetres long, with some tiny enough to fit on the end of a piece of dried spaghetti. Professor emeritus Brian Chatterton and his research group in the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences have named more than 150 species of trilobite, giving the tiny creatures a special green-and-gold connection.

Plastics under the microscope

Microscopic plastic particles are everywhere in our environment, but we don’t fully understand their impact. Jeffrey Farner, an assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, is trying to find out. By introducing micro- and nanoplastics into simulated ecosystems, Farner and his team hope to better understand how plastics break down, travel and interact in the real world.

Skeleton key

The skeleton of a baby Chasmosaurus belli discovered by paleontology professor Philip Currie is the most complete fossil of its kind. The 40-centimetre-tall dinosaur, thought to be about three years old when it died, has been crucial to understanding developmental changes in the species, including growth patterns between hatchling and adult dinosaurs.

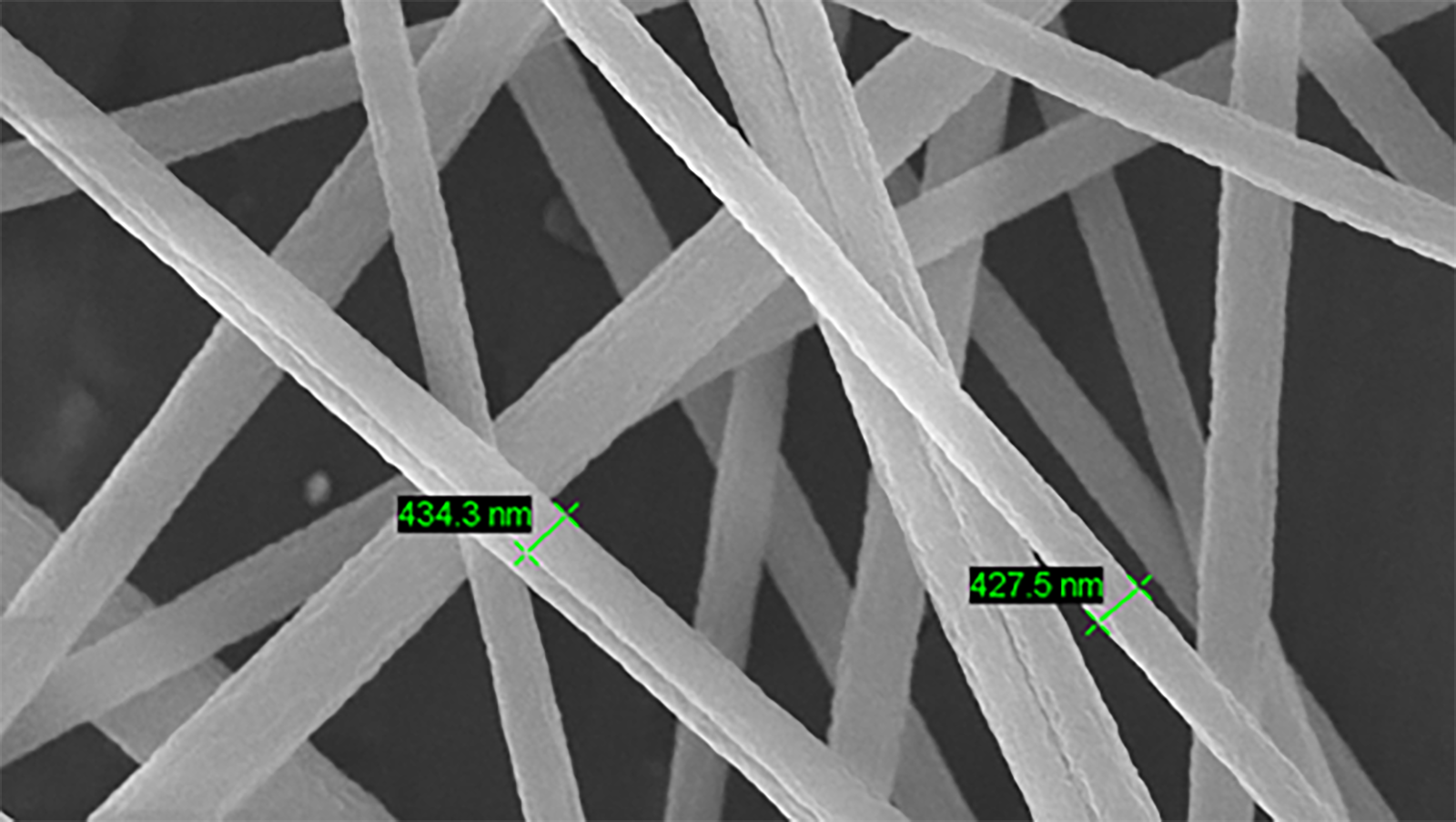

A thin line of defence

Patricia Dolez and her lab in the Faculty of Agricultural, Life & Environmental Sciences are developing self-decontaminating nanofibres as part of a multi-university research project. The nanofibres have the potential to help protect Canadian soldiers against chemical and biological hazards. Nanoscopic fibres are spun into a wearable — and comfortable — layer that may be incorporated into protective equipment to provide a higher level of filtration to prevent harmful materials from reaching the body. This image from Dolez’ lab shows nanofibres around 430 nanometres wide. For reference, a sheet of paper is 75,000 nanometres thick.

A small piece of Qing history

A 19th-century carved bamboo needle case, donated by Sandy Mactaggart, ’90 LLD (Honorary), and Cécile Mactaggart, ’06 LLD (Honorary), depicts scenes from two solar terms in the summer on the Chinese lunar calendar, which marked important seasonal and natural events. Measuring a little over 11 centimetres long, the ornate case shows figures listening to music, walking through a garden and praying for ancestors.

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.