In honour of New Trail’s 100th anniversary, we are sharing good reads from the past century of magazines. This story comes from the April 1969 issue.

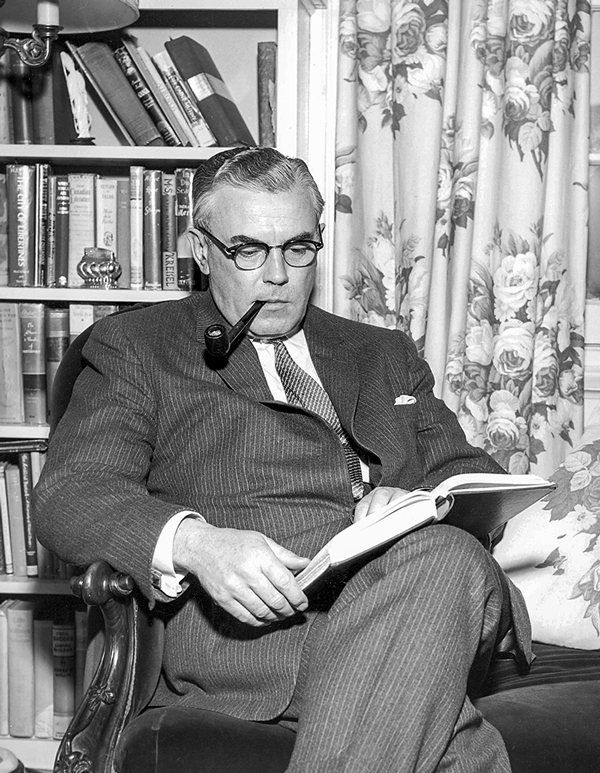

Walter H. Johns will retire Aug. 31, 1969. He has been president of the University of Alberta since 1959. He joined the faculty 31 years ago as lecturer in classics, and after a year’s sabbatical leave, it is as professor of classics that he will return.

During the decade that he has been president, student enrolment has trebled, the faculty has grown by two and one-half, and over 70 per cent of the university’s present physical plant has been constructed.

Shortly after Dr. Johns announced his retirement, the following story appeared in The Gateway. Its title there (in the issue of Jan. 31, 1969) was “Do not bend, or mutilate — this is a human being.” Its author, Al Scarth, a third-year arts student, has recently been appointed Editor of The Gateway for the coming year.

The President is busy.

He does not look up when you enter his office. An impressive stack of letters has just disappeared under his signature, Walter H. Johns, written with an ‘a’ almost as large as the ‘W’ and a ‘J’ with a monstrous stomach.

If he ignores you for the moment, there is already a hospitable cup of coffee by your chair. Funny, you didn’t notice it and sat in the wrong chair. However, you might glance about and see that it is really a very nice office, the one they reserve for the president, but then, it’s all part of the insulation, part of the attempt to shelter, protect the administration from ...

“First of all, before we do anything else,” (Oh, oh, he wants to run this show) “can you come to supper tonight?”

Huh?

“My wife will have some leftovers from a luncheon and if you don’t mind leftovers ...”

There is a private phone in the president’s office, which he must keep tabs on in addition to calls routed through his secretary. As his constant companion, it frequently makes its presence known, every few minutes: “Yup, yup, yup, yes. Well, why don’t I just send it to you? I haven’t time.”

That stack of official looking letters? He is organizing a club of former university presidents, Lucem Revidemus (We See the Light Again) is the proposed title. And there is a personal invitation for tea in Victoria which he must refuse because of a speaking engagement in Vancouver. “No time.” His secretary pleads that he sign “one little short letter, I think that’s the last one.’”

Getting around the president’s phone is like feeding your girlfriend’s little brother quarters: neither stay away for very long. “It’s not a year of loafing,” he tells it, “it’s a year of work, what the young people say today is ‘doing my thing.’”

That year starts Sept. 1, when he leaves the post he has held for 10 years to return to his overstuffed bookcase and its many unread volumes. After that you will probably find him in a classics classroom, teaching again.

But today he is an administrator and as such turns an indignant eye towards a CBC television program, “Man At The Centre,” broadcast the night before as an in-depth study of Canadian universities. One has the distinct feeling that the president of the CBC, George Davidson, a long-time friend, will soon hear the president’s complaints.

“It was supposed to be a picture of Canadian universities and it may have been, at most, part of Berkeley and Columbia. This student who said the university was run by two men, the president and the provost, or our Academic Vice-President here, and implied that the Board of Governors, none of them being educators, set the courses — this is sheer bloody nonsense and you know it is. The administration does nothing of the kind, it’s the responsibility of the instructor. lt is the responsibility of the instructor to see that what he has to teach is … and I can’t think of a better word to describe it, I think it is le mot juste ... relevant.”

“I won’t accept it, I will deny that it is a factory. The simple fact that you use technical devices does not negate the existence of a community of scholars. I believe the university is a community of scholars. I believe both the instructors and the students are learning, of course it’s at different levels. But there is a dialogue and there will be much more when I go back to the classroom than when I left because students speak up today.”

His secretary speaks up from the doorway. There is still another letter. “Can you just sign this?”

“THAT,” the President asks, “is the last one — isn’t it? If I can leave at noon I can get back from Ottawa in time for the dinner.” The secretary evaporates.

“If a student who needed to see me, didn’t, I went to see him. I collared him and said: ‘Look, you’re in trouble, what are we going to do about it.’ This is one reason I think tests are so important (not necessarily exams under pressure), otherwise how are you going to find out if the student is learning anything? You have got to find out at first-hand what the student is doing.

‘‘I have never suffered from enormous classes, never had to organize great throngs. But if you must have one or 200 students in a class, your markers must be competent.’’ Possibly, he says, the answer is in the tutorial system, at least outside the sciences. ‘‘If there was a 15-minute oral quiz, I could sure find out if he [the student] learned anything.”

But there can never be enough time.

‘‘The tragedy is that the time in university for learning is so short.” To encapsulate his point, the president pulls from an extensive repertoire the Roman proverb: Vita brevis, ars longa — Life is short, art is long.

For himself, it is a philosophy closer to that of Cecil Rhodes: “‘So much to do, so little done,’ he said that on his deathbed you know. I’m 60 now and that is the feeling you get. In the past years I have been learning the art of administration. I’ve worked hard at it. I have only touched the surface. When you expect a student to prepare himself for a place in society in three or four years, it is a lot to ask. The most you can hope is to instill a hunger for knowledge that will last the rest of his life.”

As the end of his long tenure draws close (“well, there are quite a few presidents who’ve been around quite a long time, I’ll admit there aren’t very many who have lasted as long, in fact there are very few,”) a note of regret, of powerlessness against the times, creeps into his voice. The man at the top of a careening computerized university structure (“it has a life of its own,”) cannot help but remember the 23-year-old Cornell classics and ancient history doctoral candidate who spent Christmas 1932 in an Ithaca rooming house for a sumptuous Christmas dinner of vegetable beef soup and bread. He didn’t have the $15 for a ticket home to Exeter, Ont. If it was a lonely Christmas, his memories of it are still indicative of the mood of those now incomprehensible times.

“Half of the students didn’t have enough to eat. I don’t think anyone felt put upon. It was a fact. The big challenge then was to mold the economic life of the country so we could get work for people again. There was a desperate effort by people to recover their dignity by earning their own living, to stand on their own feet. The students were very close to that, my goodness, yes.”

But now: “There are so many people here that seem almost frantically unhappy and that is most unfortunate. They seem to be hungrily seeking a life to enjoy, and they can’t find it. They can’t enjoy life as it is. They seem to be concentrating on the evils of life and complaining all the time. Of course, ills are there, and we should be trying to find out about them. Instead of complaining so frantically about those ills, maybe we should get down and try to cure them.”

‘‘I don’t think in their efforts to reform society they have to be so terribly unhappy. I don’t think we’re any happier today than when we had nothing, when my wife and I had to borrow chairs from the undertaker to entertain. Some students bring a closed mind to university. They know society is rotten, and there is no good in it. I think we were more open than that. They should be permitted to put their view forward but not permitted to ram it down everyone else’s throat — I’m right even if everyone disagrees with me.’”

If the president ever belonged to a ream of radical student organizations, he’s not admitting it. There is one, however, which he remembers with a whimsical smile, focused on the days of the idealistic student: “Veterans of Future Wars” was formed in the 1920s and dedicated to the belief that war was a silly way to settle arguments on an international scale. He still believes it but has long since discovered that, ‘‘those who refuse to study history are doomed to repeat its errors.”

But no one was listening when the young professor from Waterloo University presented his comparison of Hitler and Phillip of Macedon. Some of his predictions became horrible truths just a few years later.

Ironically, the war years put Dr. Walter Johns on the road to the university’s top administrative post, or as he puts it: ‘‘The first step down the primrose path was getting the pouring-in of returned servicemen registered.” That year, 1945, he became assistant to the dean of the Faculty of Arts and Science and began his study of the “art of administration.”

In 1957, the year of the Sputnik, he moved from the office of the dean of the faculty to the vice-president’s quarters.

“The time was right for a great thrust forward in the physical sciences. But today, the great need is for emphasis to be placed on the social sciences and the humanities. We lack so much an understanding of man in isolation and in society. There is too much emphasis on man as a puppet. Blake and Browning may not have been scientific in the modern sense that if you stick a pin in a man here, he jumps one foot, and if you stick it there, two feet, but they have something to say.”

“We might approach a knowledge of man by restudying the views of the great minds of the past, and one of the best sources is the Bible or the great Greek and Roman classics, or through Heine, Goethe, Racine, Moliere.”

As for 1959 and the presidency: “Well, I think I could say it was perfectly obvious that someone had to do it and I was prevailed upon to accept, that it was my responsibility, and I should get on with it.” He describes it as more of a draft than anything else.

The president is no politician. He wonders how The Gateway editor would feel if his position were subjected to the electoral process in a manner similar to that proposed by the paper for the selection of presidential successors. He says no worthwhile candidate would allow his name to stand for an elected presidency.

The man who paid the tribute to Premier Manning upon his retirement “can’t understand why anyone wants to be a premier of Alberta, prime minister of Canada, president of the United States.”

Nor can he understand the sometimes ‘‘vicious,” sometimes “destructive” actions of students.

“They’re desperately serious, these long-haired types. I can’t help get the feeling sometimes, maybe I’m wrong, that their actions are malicious. They should try to see the possibility of good things instead of only the relentless march of evil. Some of them seem to have, I was going to say, lost hope. At best they are terribly, terribly pessimistic about reform of society.”

“They’ve lost their sense of fun. Certainly, a lot of these people have no sense of humour. And, of course, their response would be there is nothing to be funny about.”

In the main, the president believes that students from the Western provinces, because they are closer to the pioneer period of our national growth, have a greater appreciation of the value of education. “They come here with a pretty serious idea about getting an education. It is the same in the Maritimes. But in the East, they reflect the urban unhappiness of the older cities.”

At this university, he sees two related, major concerns his successor will have to grapple with.

“One is the emphasis on research, which to be effective must in most cases extend our knowledge on a narrow front, and it means people become more and more narrowly specialized. At the undergraduate level, it is at least very unfortunate because at particularly this level you need a person with a broad knowledge of the field. The emphasis is on research to the exclusion of instruction at the undergrad level. Professors, more interested in research than teaching, take on a teaching position and their interests are too narrow.”

The president considers much research to be no more than “occupational therapy for professors.’’

His hope that we might have graduate programs that encourage breadth of approach, instead of depth, is now “certainly not looming on the horizon.”

Walter Johns lost something very special when he left the classroom — close contact with his students, a something that is very precious to him. It is a loss he mentions at the supper table when he speaks, over the ice cream, of the students’ automatic response of fear towards the president’s position. The motto of the Berkeley students — “do not bend, staple or mutilate, this is a human being” — applies just as much to this man as any (although he might prefer to see it translated into Latin).

Dr. Johns lives in that big house on the northwest corner of the campus. If, once upon a time, he had to rent the undertaker’s chairs, now he has a living room he doesn’t live in. There is a smaller room visible from the lobby-like entrance. It is comfortably untidy; its furniture is comfortably worn. Here is where a man can lean back, set down his glass of vermouth or Scotch and water without fear of staining the furniture, crack open the day’s paper — and read about all the student unrest.

There are two things in this house of which he is particularly proud. The first is the collection of paintings that lines the walls of the spacious home. The second and more important is his bulging bookcase.

In this case there are rows behind rows of books. “Where is it, well, it’s here somewhere, I hope. l may have loaned it to someone and not got it back.’’ He finds it — Mostly in Clover by Harry Boyle.

“This is exactly what I went through: mortgages, country characters, the hired man. Here, I have a real jewel that I hide.” After much rummaging: “That’s an Elzevir, printed in Amsterdam in 1671. If you want a real old one, it’s a bit mouse-chewed but 1602.

“Oh no! Here’s the real jewel: The Bubbles of Canada by Haliburton, 1839. I got it for 50 cents in a little place in B.C. I told him I thought that the book was more valuable but he said ‘not to me it ain’t,’ so I bought a $7.50 Letters of Queen Victoria and felt a little better.”

Another book leaves its place and is eagerly thumbed through: “All these plates, beautiful plates, real pretty ones — if you like that sort of thing,” he adds with a worried glance in case this is boring the onlooker.

So, Dr. Walter H. Johns will leave his post, move his books and start his research for a history of the university to 1967. It still hurts him when he speaks of the university as a place of learning and light, and people say: “Oh yeah!”

We at New Trail welcome your comments. Robust debate and criticism are encouraged, provided it is respectful. We reserve the right to reject comments, images or links that attack ethnicity, nationality, religion, gender or sexual orientation; that include offensive language, threats, spam; are fraudulent or defamatory; infringe on copyright or trademarks; and that just generally aren’t very nice. Discussion is monitored and violation of these guidelines will result in comments being disabled.