As a high school student, Katie Bidulock wasn’t taught about Indigenous peoples and their histories in Canada, so those lessons were startling when she went on to train as a teacher herself.

“I’m one of a generation that didn’t talk about it in school, and I graduated in 2000, before any of the big reports (such as the Truth and Reconciliation Commission reports) came out, so I felt very surprised about the learning I was suddenly doing in university. I was shocked at the history, and whose voices were missing in the learning I had done up to that point.”

Now a high school teacher, Bidulock considers it vital to learn — and keep learning — about Indigenous peoples, cultures and issues.

Indigenous Peoples and Canada, a new micro-course created and offered through the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Native Studies, has made that continuous learning convenient for Bidulock, who took the short course to build her understanding, both as a professional and as a citizen.

“It’s my responsibility as a settler and as an educator to have deep knowledge I can keep current with and share with my students.”

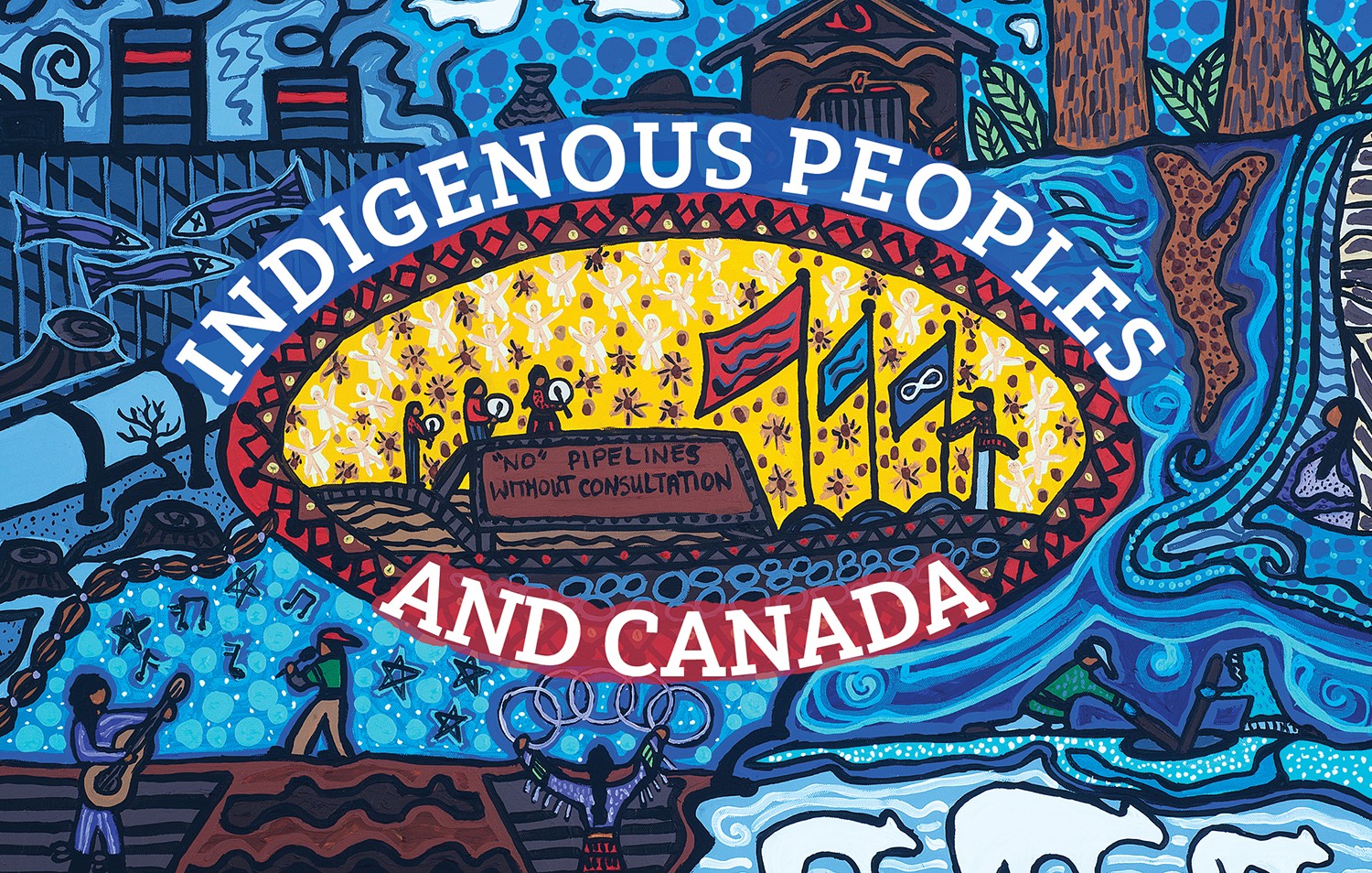

Inspired by Indigenous Canada, a popular online offering of 12 lessons exploring the diverse histories and contemporary perspectives of Indigenous peoples, the micro-course, which starts Oct. 11, offers a condensed, more accessible version, says instructor Paul Gareau.

“It’s a good basic tool for workers in the private and public sectors to engage in. They can apply it to their own work in Indigenous engagement in fields like education, legal structures and government.”

The online course, requiring eight to 10 hours of work, is somewhat of “an Indigenous Studies 101,” he adds. “It’s useful for a vast majority of Canadians who don’t have any Indigenous knowledge at all.”

Divided into six modules, the lessons explore historical and contemporary experiences of Indigenous peoples, to guide participants in understanding the legacy of settler colonialism and learning about Indigenous self-determination.

“The course focuses on Indigenous resiliency and capacity, to help dispel racist narratives,” Gareau says. “It’s about shifting your mind to be open to understanding Indigenous experiences a little further, to say let’s take a moment to look at how things aren’t equitable, and to push back against structural racism, because that will dispossess everyone, every time.”

The curriculum includes lessons on Indigenous worldviews and genders, particularly focused on the importance of women to Indigenous governance, leadership and relations. It’s a viewpoint that “challenges settler colonial perspectives, which are what lead to issues like racism,” says Gareau.

Learners also explore resource, economic and land management through the lens of Indigenous relations — showing, for example, how the early fur trade was not created by settlers but was in fact co-built by Indigenous people.

“It shows that Indigenous peoples have always had capacity for engaging in economic activities and governing the land, but through relations, which is different from settler perspectives geared towards capitalism and individualism,” Gareau notes.

The course also provides a look at Indigenous governance, treaty and law, “with a focus on showing what treaties are and how they are an important part of how Indigenous peoples govern themselves,” he says.

“People taking the course should gain an understanding of how relations work through these legal structures, and also how the state has manipulated some of these treaties and not kept their side of these bargains. This is a history not many settlers are learning.”

Also covered in the course are Indigenous experiences of institutionalization in residential and day schools, which dispossessed Indigenous peoples, moving them off their land so it could be used for resource extraction and settler development, Gareau says.

People are also encouraged to think about broader systems like incarceration and church-organized religion, he adds. “It can help learners question the structures we are complicit with now.”

And a section of the course challenges the “erasure” of Indigeneity from Canadian society, reinforcing how “Indigenous peoples are still here, still living, and succeeding” in modern society, he adds.

A final chapter focuses on Indigenous activists and artists, showing how their work is vital.

“Indigenous protests are a form of protecting relations, land and water, and political movements emerge because Indigenous artists tell stories of their people,” Gareau notes. “We want to show that Indigenous people are engaged and still important.”

Bidulock says she now has a deeper understanding of the importance and purpose of their work.

“Sometimes when we learn as non-Indigenous people, we learn about the hard parts of history and then it stops; we don’t necessarily talk about the revitalization of community or actions to achieve change. So it was interesting to learn more about the activists and artists who are helping to expand and change the narrative.”

Overall, the course has encouraged her to become more of an active ally to Indigenous people, adds Bidulock. One of the class assignments, for example, was to write to a member of Parliament about a pressing issue; she wrote about the need to ensure clean drinking water for Indigenous communities.

“I appreciated being asked to do it, as something that may not impact me directly but that I care deeply about. I’m going to advocate more for Indigenous issues that can benefit from additional voices.”