Metabolites produced by gut bacteria during digestion can be used to trigger an immune response against colorectal cancer cells, according to new University of Alberta research that points toward a potential treatment for one of the deadliest forms of cancer.

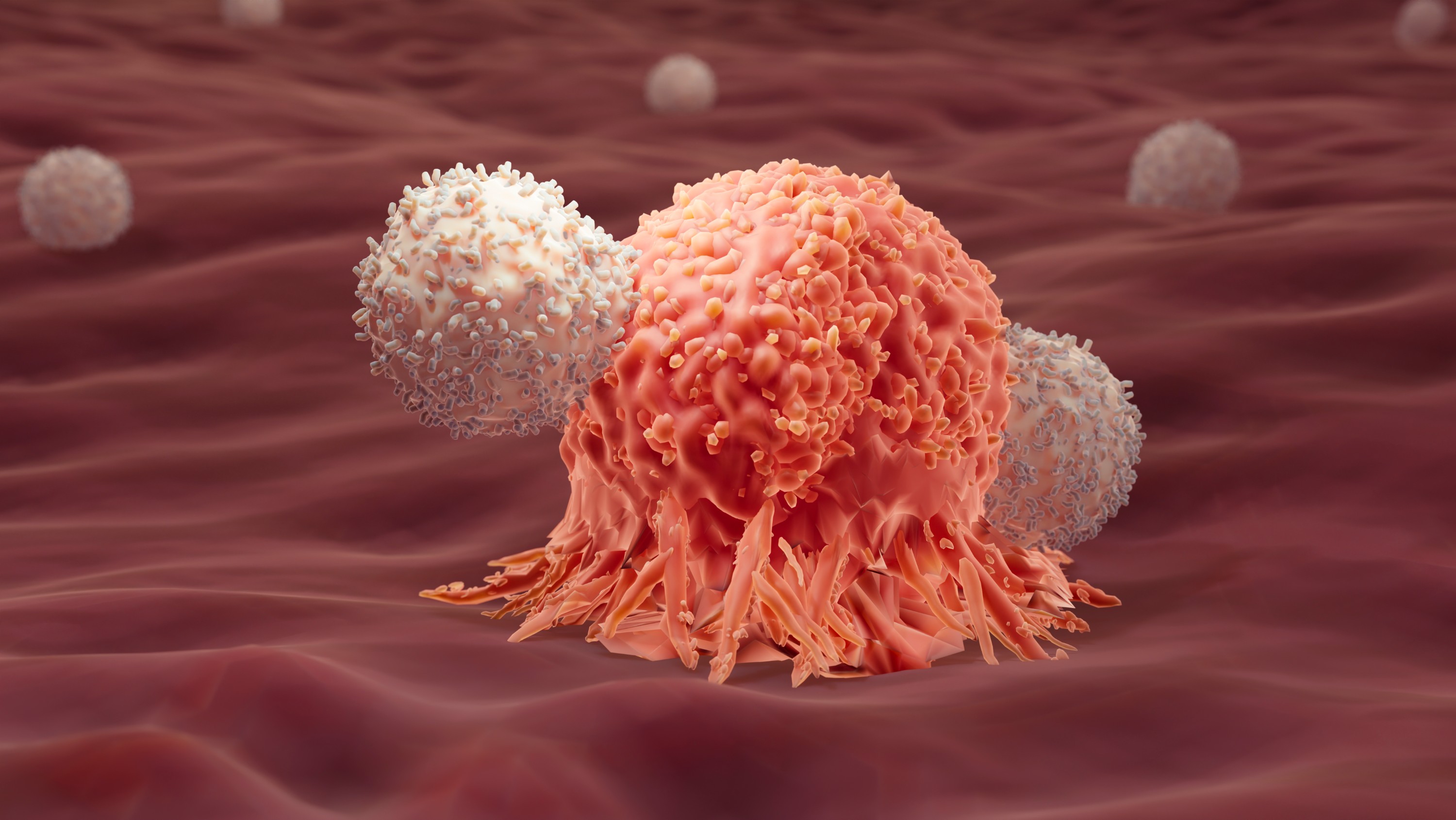

The research team found that the metabolites activate a molecule on the surface of the cancer cells that attracts immune cells, called T cells. The metabolites are also able to enter the nucleus of the cancer cells and alter their DNA, which further attracts the attention of the immune system.

“What we saw is that these products regulate a key molecule on the tumour cells that T cells directly interact with, so it provides a way for the T cells to detect that the tumour cell is there, that there's something wrong and that they want to eliminate it,” explains Kristi Baker, associate professor in the departments of oncology and medical microbiology and immunology.

“The products were also making changes in the cell’s gene expression, which co-ordinates interactions between the cancer cells and the immune system,” says Baker.

Colorectal cancer is the second most lethal cancer for men and third for women, according to the Canadian Cancer Society, which estimates 9,400 Canadians died from it in 2022.

Baker’s trainee Courtney Mowat led the research and carried it out with the help of undergraduate students Jasmine Dhatt, Ilsa Bhatti and Angela Hamie.

“We hear a lot that a diet high in fibre is very beneficial and potentially protective against cancer, so part of the question we were asking was how fibre could be contributing to cancer protection,” explains Baker.

The team tested two of the most abundant metabolites produced by gut bacteria as they digest dietary fibre — butyrate and propionate. The researchers exposed cancer cells in the colons of mice to the metabolites to observe their lasting effects. They also tested the metabolites on human cancer cells in the lab to confirm the results.

“I was really surprised by the fact that the response was so strong and that it was so reproducible,” Baker notes.

Baker plans to continue her research to better understand the mechanisms involved in the response, in hopes of one day seeing the research used to develop prognostic tests or new cancer treatments. She will test the metabolites in different concentrations and combine them with immunotherapies to see how effective they are against different types of cancer cells.

“For example, if we find a patient who doesn't have a lot of the bacteria that naturally produce these particular metabolites, maybe they could take a pill that would basically turn on those same pathways in order to boost the immune response,” she explains, noting that simply eating more dietary fibre would likely not produce enough of the target metabolites.

The students involved in the study received funding from the Alberta Cancer Foundation. Baker’s laboratory is supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, the Canada Foundation for Innovation, the Cancer Research Society and the University Hospital Foundation. Baker is a member of the Cancer Research Institute of Northern Alberta and the Women and Children’s Health Research Institute.