Ashwin Iyer knows he isn’t cut out for combat.

But the electrical and computer engineering professor has long wanted to help keep Canadian soldiers safer on the battlefield, and he’s hoping his recent funding from the Department of National Defence will make that possible.

Iyer has received $1.5 million in contribution agreement funding from the DND’s Innovation for Defence Excellence and Security (IDEaS) program to improve communications between soldiers in the field and central command, conveying critical information about troop health and situational awareness in the harshest of combat conditions.

Using cutting-edge technology, including numerous wireless sensors attached to a soldier’s body and tiny antennas to transmit data, offsite commanders will be able to track the condition of their troops in real time.

Commanders would see a visual display of vital statistics such as heart rate, respiration, muscle fatigue, catastrophic damage to organs, and perhaps even brain activity.

“If somebody's critically injured, or if they are fatigued or vulnerable in some other way, can we monitor that to arrange for assistance, regroup or determine how much time we have left to get them out?” asks Iyer. “The system relies on a constellation of compact, power-efficient sensors, sensing as many biometric properties as possible.”

There are some challenging hurdles in successfully designing such a communications system, says Iyer. But his team has a big head start, thanks partly to pioneering work on wireless sensors by U of A researchers Pedram Mousavi and Mojgan Daneshmand, the husband-and-wife team killed three years ago on Ukraine International Airlines flight PS752, whose work is being carried on by Iyer and one of his partners on the DND contract, Rashid Mirzavand.

“What we envision relies on state-of-the-art technologies, many of which were not available even five years ago,” says Iyer. “Science fiction authors have written about it. Video game designers have conceptualized it. Now we have the audacity to actually propose it.”

To start with, antennas that receive and transmit signals are typically only effective when they are at least half a wavelength long. That means at a standard frequency in the UHF range, such as 900 megahertz, an antenna has to be nearly 17 centimetres — far too big to be practical in combat, considering the number and density of on-body sensors requiring these antennas.

Today’s cellphones use a number of tiny antennas that aren’t as efficient as they could be, says Iyer. Circumventing these limitations could provide opportunities to avoid interception, drop-outs or jamming of signals in the field.

“We’re building small-antenna technologies that are robust even under the harshest scenarios.”

One way around the size limitation is to use “meta” materials — materials engineered to have “properties that you don't find in nature,” says Iyer.

“If you can make materials with designer properties, then you can make devices with designer performance.”

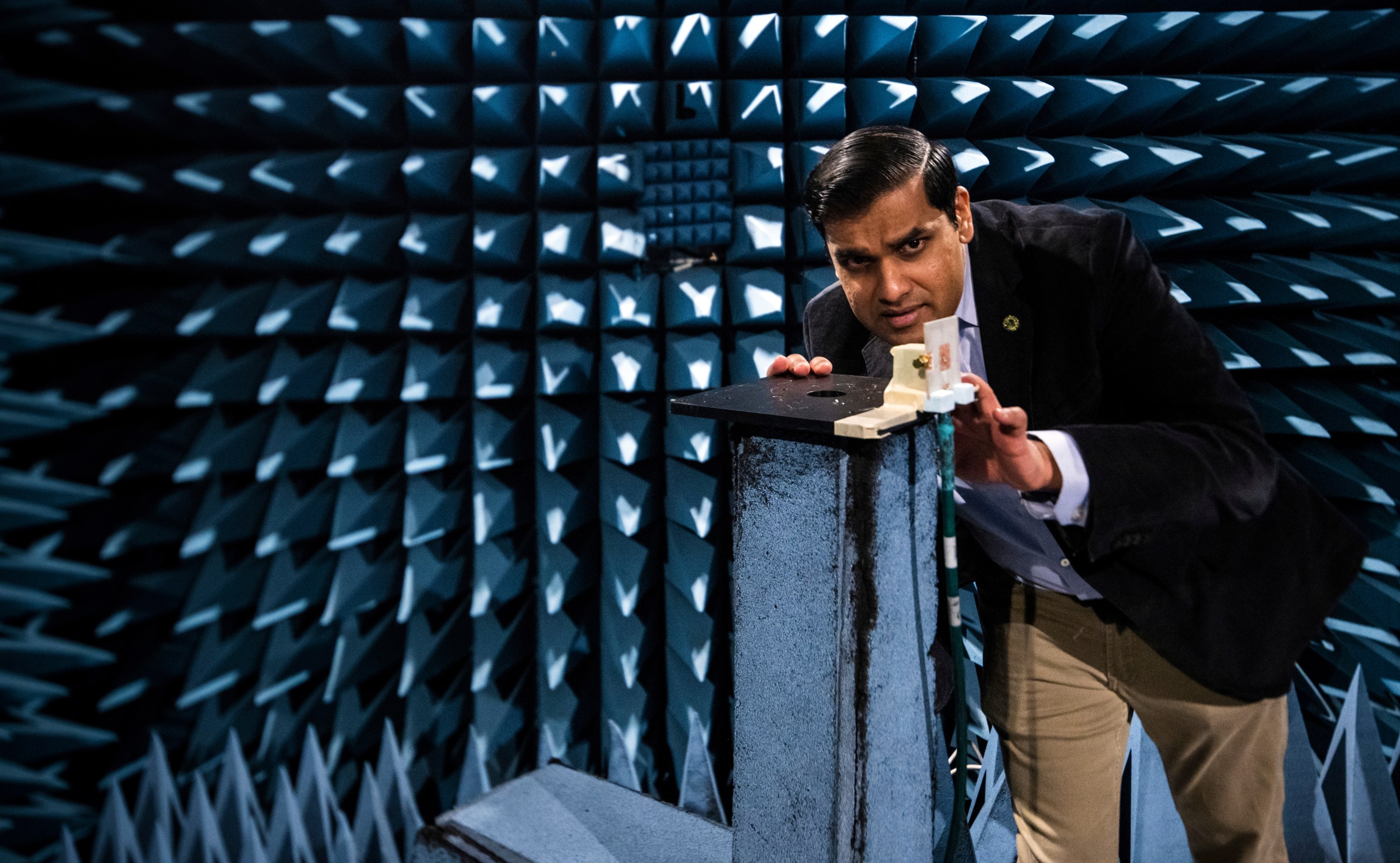

Iyer’s team uses circuit configurations inspired by metamaterials to infuse antennas with new properties — for example, to change how they interact with waves. He’s not just making antennas smaller; he’s changing their fundamental properties.

Another design hurdle is power. Soldiers may not be able to rely on batteries in harsh scenarios in the field, so the researchers are striving to make the system battery free or capable of operating with extremely low power.

“Prof. Mirzavand’s expertise in making sensors without batteries is invaluable to the project,” says Iyer. “His sensors harvest electromagnetic energy from the ambient environment to do their jobs, and can incorporate other types of energy harvesting as well.”

While Iyer’s ambitious research mission is sure to encounter challenges along the way, he and his team are excited at the scientific prospects that will result, and motivated to use this new science to solve a myriad of problems under what DND calls situational awareness.

“We’re training students, and the military understands and encourages that,” he says. “The people on this team have enough credibility to solve most of these problems in whatever shape that eventually takes. And we’re always looking for top-notch graduate students and postdoctoral fellows who share our vision and purpose.”

The three-year contribution agreement funding from IDEaS — with the potential to extend further — will employ between 12 and 15 graduate students and post-doctoral candidates, and possibly some undergraduates as well, says Iyer.

In addition to other researchers from the U of A, Iyer will collaborate with researchers at the University of Toronto, Toronto Metropolitan University, Queen’s University, the University of Waterloo and UBC Okanagan, as well as industry partners Meta Materials Inc. and AUG Signals.

Iyer says the research has personal “philosophical meaning,” since its aim is to save lives and mitigate conflict.

“This technology will keep soldiers safe and extend their lives on the battlefield. It will keep them more aware of what's happening around them and give them a better chance of survival.”