A University of Alberta dairy researcher is picking up where scientists left off 40 years ago, trying to solve an ongoing problem with calf health.

Up to 30 per cent of dairy calves worldwide don’t get enough vital antibodies before birth to ward off the risk of diarrhea caused by E. coli and other bacteria. The condition can be deadly to the young animals, said Becs Hiltz, a PhD candidate in animal science in the Faculty of Agricultural, Life & Environmental Sciences.

Though calves do get antibodies through colostrum — their mother’s milk — they don’t develop immunity right away.

“Calves are born with a functional immune system, but it is slow and can take two to three weeks to respond to any sort of disease they may encounter.”

In addition, they can only absorb the antibodies within the first 12 to 24 hours of life — something Hiltz wants to change through a better understanding of how the antibodies are absorbed.

The last research exploring that specific function was done in the 1980s.

“I want to start up where those studies left off”

Colostrum quality has since been improved to boost the levels of antibodies fed to calves, but the rates of antibody transfer have not changed, because not enough is known about absorption itself.

“It’s not been an issue we’ve been able to improve our knowledge on, and I want to start up where those studies left off and keep pushing forward,” said Hiltz, whose work is part of the ruminant nutrition research program headed by Professor Anne Laarman in the Department of Agricultural, Food & Nutritional Science.

“With advancements in understanding antibody absorption, we could change how every dairy farmer in the world feeds their animals.”

Through a 2019 study she did as a master’s student, Hiltz was able to determine that butyrate, a fatty acid that increased antibody uptake in piglets, had the opposite effect in calves by actually decreasing their already brief window of absorption.

While the findings eliminated one potential solution to the absorption issue, it also showed Hiltz that it was possible to manipulate that time window.

“I thought, if we can decrease it, maybe we can increase it, but there’s more we need to know before we can do that.”

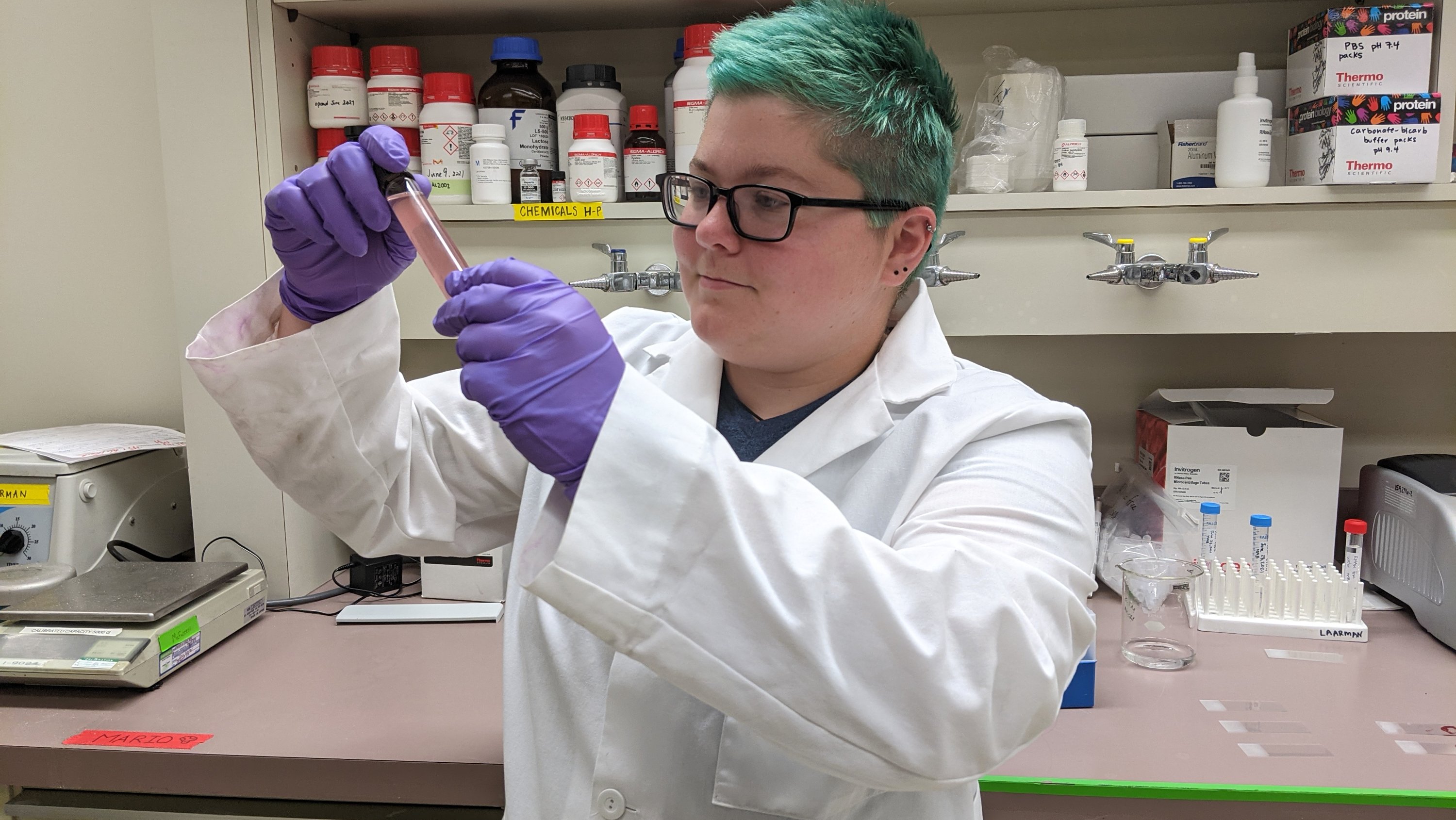

Hiltz then developed labelling techniques to help determine absorption efficiency, rate and timing, then tested them on an Alberta dairy farm.

The first method works by attaching a protein called biotin to the antibodies in the colostrum.

“Biotin is not common in cows’ blood, so when we measure it, we know it is our label and not something else. If we feed colostrum at birth and then the biotin at different time intervals, we can measure absorption happening at those different times. This allows us to get a snapshot of the absorption process.”

Hiltz also developed a second label by attaching gold particles to antibodies that allow her to observe absorption at a cellular level in the gut to pinpoint where absorption happens.

Widening the window of opportunity for antibody absorption

The pilot study showed that the labelling systems do work, Hiltz said.

“We were able to figure out the correct dosing for the labels. We found out that the maximum absorption was occurring in the middle of the intestine, allowing us to focus there for future studies.”

She’ll test the methods more extensively this fall, and expects her work will ultimately contribute to improving the absorption process overall and possibly widening the narrow window of time calves have to absorb the antibodies.

“That gives the farmer more time to get colostrum into their calves, especially those born overnight or between work shift changes. If we could get the absorption window to two days instead of 12 to 24 hours, that would be incredible,” she said.

Calves are a big investment for dairy producers, requiring two years of feeding before they start giving milk, she noted.

“How a calf is fed in its first hours of life will affect its milk production two years down the road; if calves get enough antibodies, they’ll produce more milk in their first two lactations. So the first four hours of life is essential to get colostrum into calves, and any extra time we can give farmers is going to be huge.”

Hiltz’s work is supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada, Zinpro and the Alberta Milk Endowment Fund.