It never occurred to Peter Young that he might get diabetes, even though his mother and other family members have the disease, and he had lost a childhood friend to an uncontrolled diabetic foot infection.

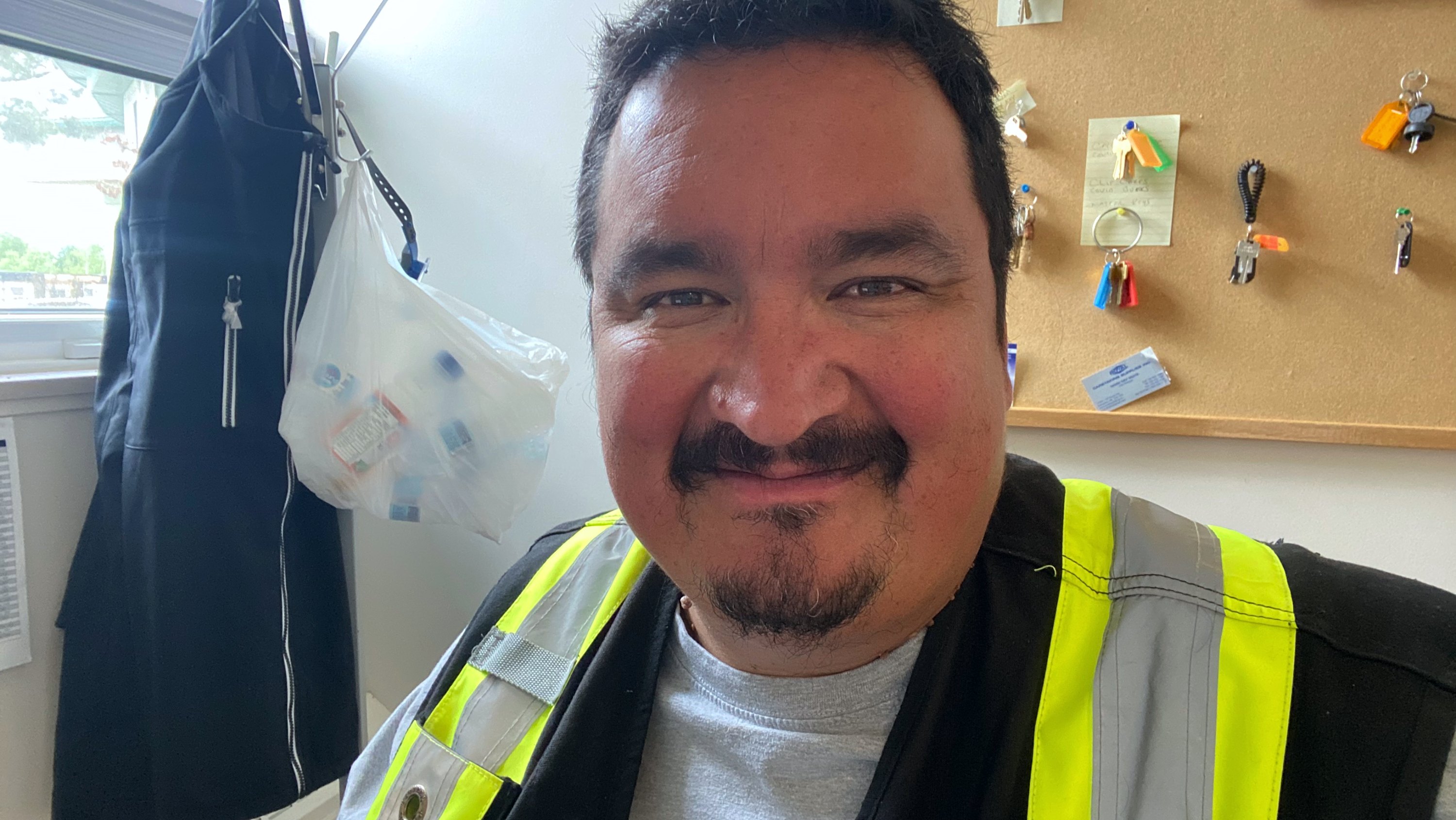

“I didn’t know how diabetes works,” said the 44-year old member of the Bigstone Cree Nation in Wabasca, 322 kilometres north of Edmonton. So when the telltale signs of Type 2 diabetes began to plague him last summer—lightheadedness, an unquenchable thirst, urinating every hour—“I didn’t have a clue.”

“When the doctor gave me the news, I got in my truck and I just cried,” Young said. “It was such a shock. I thought, ‘My life is over, I can’t have any fun stuff anymore.’”

Luckily, Young got support to manage his illness. An innovative new program developed by First Nations from treaties 6, 7 and 8, a health-care social enterprise, and researchers at the University of Alberta, is revolutionizing care and improving outcomes for First Nations members across the province.

Young, a maintenance supervisor, has now wrestled his blood sugars back into the normal range with a daily regimen of medication, exercise, meal planning and finger-prick blood tests when needed. “Now I have my breakfast in the morning, my lunch and my supper,” Young said.

“I’m not eating as many fatty foods, I'm eating lots more fruit and drinking lots more water. If I have something sweet, I'll walk it off.”

Changing lifelong habits has been tough, but Young has been helped every step of the way by Jessica Oickle, the registered dietitian at the Bigstone Health Commission. Along with sharing nutrition information, she explains how his medication works and gives him regular reminders to get his blood work and other checks done.

“If I didn’t have Jessica helping me, I probably would have tossed it aside,” he said.

Adapting to each community’s needs

Bigstone Cree Nation is a founding partner in the RADAR program, which stands for Reorganizing the Approach to Diabetes through the Application of Registries. It was started six years ago to help support diabetes care in First Nations communities in Alberta.

Diabetes rates are three to five times higher among Indigenous peoples in Canada compared with the general population, and deaths are also higher, due to social determinants such as lower incomes and poorer access to education, health care and healthy food, as well as stress related to historical discrimination and racism, said Dean Eurich, epidemiologist, professor in the School of Public Health and head of the research program to evaluate and refine RADAR.

The RADAR program uses an electronic health record system created by OKAKI, a health-care social enterprise. Patients with diabetes are identified and registered, and needed services such as foot care or nutrition counselling are prioritized. Then a care co-ordinator is assigned to provide teaching and weekly support for the nurses, dietitians, pharmacists and other front-line staff who deliver diabetes care within the community. The program started with two First Nations and has grown to include a dozen, with several more poised to join when the COVID-19 pandemic has ended.

Since the program began, Eurich said more than 700 patients have improved by an average of 10 per cent in key metrics such as blood sugar, blood pressure and cholesterol levels. The research team also recently published positive results from a qualitative survey of front-line staff. RADAR is funded by the Lawson Foundation, Alberta Innovates and Canadian Institutes of Health Research, and supported by the participating First Nations and OKAKI.

“We spent time building relationships to get meaningful input,” said Eurich, who is a member of the Alberta Diabetes Institute. “RADAR can be a great benefit to the community because it’s culturally appropriate.”

“It’s very pragmatic and adaptable and not prescriptive, because each community has different wants and needs.”

Empowering each client

Jessica Oickle, Bigstone’s dietitian, puts each patient’s needs first by asking respectful questions, listening and providing timely information.

“In a lot of health-care delivery models you come in, sit down, you’re told to do this, take that medication, see you later,” she said. “It’s not a conversation, and it’s not empowering to the client at all.”

Oickle estimates she spends about 90 per cent of her time helping people with diabetes learn how to manage their illness. Brought up in the Bear River First Nation in Nova Scotia, she saw her uncle pass away from diabetes-related complications with no diabetes services available in his home community. She sees it as a symptom of a greater, systemic injustice.

“I think speaking about diabetes isn’t enough,” Oickle said. “Many Indigenous communities are often living in a disenfranchised state—by that I mean people living with no water, no transportation, no access to food, housing disparities, mental, physical, sexual and emotional abuse, as well as multiple chronic health-care conditions.”

Oickle sees her role as ensuring that members of Bigstone Cree Nation who have diabetes know they don’t have to cope with it alone. “We always have a team that’s looking out for them.”

Supporting the team that supports the patients

At the RADAR office, helping Oickle deliver on that promise, is Kari Meneen, program lead and care co-ordinator with OKAKI. A registered nurse, Meneen is from Tall Cree First Nation in northern Alberta. During her studies she worked on a report about Indigenous health as a research assistant for Alberta Health Services. What she learned propelled her into the field of diabetes care.

“Indigenous people have higher rates of diabetes-related kidney complications, amputations, and dialysis,” Meneen said, “but what really hit home for me was the poor access to care—not being screened and not being able to access the specialized services needed.”

She noted that some First Nations struggle to provide the basics of care because resources are limited. “For example, the clinical practice guidelines recommend that each patient should have a foot exam every year,” she said. “When I say that to a front-line provider in the community, they feel it’s impossible, because the nearest foot care nurse may be three hours away in the city.”

Meneen works to help build capacity within the communities she supports, whether it’s foot care training, screening reminders or support with the electronic health record system. She has offered a study group for community staff who wanted to take Canadian certified diabetes educator training. She is now working to add more social and cultural elements to the diabetes education she provides.

Creating sustainable change

RADAR will run until at least 2024, and the legacy it leaves for each community is key for Eurich.

“We are very cognizant that this should be sustainable after the research funding is gone,” he said. “We’ve heard lots of stories about researchers coming into First Nations communities, doing their program, then leaving, and the community is left with nothing.”

“The university has a responsibility to address inequities in diabetes and chronic disease care for marginalized populations, not just in Alberta but across Canada.”

Peter Young now tells his story to friends and family as a cautionary tale. He’d like to see more education programs about diabetes and its impact on Indigenous peoples.

“Coming from these small communities, doctors don’t make us aware,” he said, noting that his blood work the year before he was diagnosed showed he had pre-diabetes, but he wasn’t told. Lifestyle changes at that point might have staved off the development of full-blown diabetes.

Young is taking his diabetes self-care one day at a time, with support from Oickle, hoping to stay well so he can watch his 16-year-old son graduate from high school and his two grandkids grow up.

“I’m not scared any more,” he said. “I know the treatment of diet, exercise and (diabetes drug) metformin works.”

“It’s still a big burden. It’s something I know I have to look after. I plan to make the best of it.”

This month, the University of Alberta celebrates 100 years since Canadian scientists, including U of A biochemist James Collip, discovered and purified insulin, making it possible to live with diabetes. Since then, research breakthroughs at the U of A have continued to make life better for people living with diabetes and theirfamilies. Today, with support from partner organizations and donors such as the Allard Foundation, DRIFCan and the Alberta Diabetes Foundation, we are closer than ever to a cure. Read more about diabetes research.